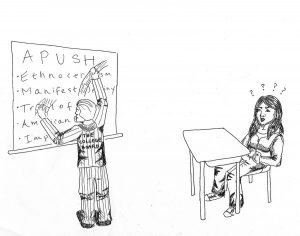

Last spring, while many current seniors were preparing for the AP U.S. History (APUSH) exam, critics voiced their complaints about the College Board’s newly updated APUSH course framework, which functions as a set of guidelines for teachers to use. The Republican National Committee (RNC), one of the foremost critics, claimed that the framework presented a “radically revisionist view of American history that emphasizes negative aspects of our nation’s history, while omitting or minimizing positive aspects.”

The 2014 APUSH framework that came under fire had sought to shift away from rote memorization of facts and dates to focus on the development of critical thinking skills. The College Board defended its new framework by saying it was just an outline for the course, rather than a rigid curriculum; implementation of “key concepts” and “learning objectives” would be left to the discretion of individual teachers.

The discontent with the 2014 framework evolved into public outcry for the College Board to make a more substantial change. The swell of dissatisfaction with the College Board’s initial response captured the attention of such notable politicians as Republican presidential candidate Ben Carson, as well as state legislators in a handful of states.

The RNC called for a return to the “course’s traditional mission” that would allow “students to learn the true history of their country.”

The College Board caved, issuing a new set of guidelines in July of 2015. The response from critics has been mixed, with some satisfied with the changes. Others, however, are still convinced the framework leans too far left on the political spectrum.

The College Board’s critics were correct to encourage a non-biased view of American history. But that does not mean that historical events that shame us should be erased.

The “true history” of one’s country includes everything—both the honorable and the dishonorable.

History depends on perspective. When you look at everything with a closed mind, you can miss out on understanding the motivations behind people’s actions. AP U.S. History must remind us that we’re looking at American history through an American lens.

Reflecting on uncomfortable times in our nation’s past through multiple viewpoints is not unpatriotic—it’s essential. Yet here we are, with curriculum that threatens to close our minds further. Do we simply want to read about wars we “won,” and why we’re “better” than other countries? When we approach history with an attitude of unfaltering American exceptionalism, we fail to examine ourselves critically; ignoring outside perspectives completely misses the point of learning our nation’s history.

As a country, we have committed our fair share of wrongdoings, and it would be a mistake to hide them from students who want to discover for themselves what it means to be American.

American History courses are not meant to praise everything Americans have done. Exposing historical injustices is a crucial part of examining our nation’s evolution and transformation. Sometimes it’s unnerving, but we have to confront the consequences of our actions and hold our nation accountable for imperialism, nativism, and the negative outcomes of “Manifest Destiny.”

Excising events out of the APUSH framework in an attempt to avoid discomforting discussions does not mean they did not happen.

It is detrimental to students’ personal and academic development to shield them from the most shameful parts of our history by redirecting them toward the events and ideas that make us comfortable. Our nation will not advance by whitewashing the blemishes of its past; the progress we’ve made is a result of truly understanding where we have fallen short of our ideals and learning how we can improve.

Rather than lecture students to be more patriotic and to respect authority without question, as some critics wish, we should encourage them to draw their own conclusions about our country’s history and to question authority, respectfully. This, in turn, ensures the sustainability of a healthy democracy.

We do not want a citizenry that blindly supports the country without shaping its own views, clinging to American exceptionalism as its rationale. Our tendency to see things from only our point of view perpetuates the idea that the U.S. is better than all the rest. We must consider all perspectives and not just the one we find most convenient.

So, let’s ask ourselves—by failing to provide our students with all of our history, are we encouraging them to develop their own beliefs and opinions, or are we doing them a disservice?