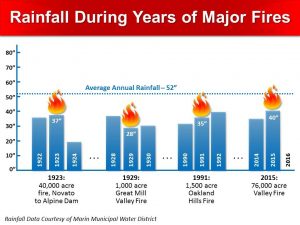

Lack of rain fueled past fires

By Andrew Hout and Keely Jenkins

In 1929, The Great Mill Valley Fire destroyed 110 homes and caused more than a $1 million in damage. During that year Marin County saw extremely low amounts of rainfall (fewer than 30 inches) and it marked the beginning of a 6 year drought (1929-1934). This was the first drought of the 20th century.

It was a hot summer day of 98 degrees and winds were up to 35 mph. This fire was the most disastrous fire of Marin’s history, from a monetary standpoint, even though it was contained at 1000 acres.

The largest fire in Marin’s recorded history occurred in September of 1923, when flames engulfed 40,000 acres from Novato to the Alpine Dam.

The next year had the lowest amount of rainfall in Marin’s recorded history: fewer than 20 inches. Although last year Marin County received fewer than 40 inches, the amount is still not enough to replenish the brush or end the drought.

All of these fires occurred in years of low rainfall and show that fire risk is more prominent when in the midst of a drought.

Marin is no exception, since dry grounds with the addition of an Indian summer indicates that the possibility of a vegetation fire, like the one that destroyed Lake County, is alarmingly high.

Tales of Uncertainty: Fire victims respond to sudden tragedy

By Gregory Block and Henry Tantum

A truck melted to the ground. A house burned to ash. A lone street sign, looming over a deserted road. The night of the fire, people were forced to leave everything behind to raging flames. And then, they were forced to wait, uncertain of what would come. Everyone affected by the fire has a different story to tell, some of escape, some of loss, and some of uncertainty.

Just Get ‘er Done

“Sort of the country way of doing things. You band together, pull together, just get ‘er done.”

– Roy Sabraw

https://vimeo.com/141847046

Roy Sabraw sits on the bed of his truck, his dog at his feet, with glints of sadness in his eyes. He ponders his own good fortune, but also the losses of his friends and community.

Sabraw’s home was one of the few that survived the Valley Fire in the first few nights of the disaster in early September. Thanks to his efforts the night the fire began, his house withstood the blaze. The fire impacted Sabraw not through physical loss, but through the emotional toll of uncertainty.

Sabraw, 75, is a Middletown resident who lives on a ranch in the area. As the flames approached, Sabraw cut a firebreak and hosed down buildings on his ranch to increase the chance it would survive the fire. Although his house was untouched by the fire, he was unaware of this until many days after the evacuation. For Sabraw, that uncertainty made leaving very difficult.

“Leaving like that is rather strange in a way that when you go away for a weekend or a week… you have a home to come home to,” Sabraw said. “But when you don’t know if you have a home anymore, [it’s a] strange feeling. I’m 75 years old and I’ve never had that feeling before.”

Uncertainty was pervasive throughout the evacuation camps. Most residents were ordered to evacuate with very little notice due to the rapid pace of the flames. They were forced to leave behind the majority of their possessions as well as their homes, with little idea of what would happen. To make matters worse, most evacuees were unable to receive information about the state of their homes or belongings, according to Sabraw.

Although his home did not perish, Sabraw said his friends lost barns, homes, and livestock. The more time he spent in the evacuation site, the more he wanted to return home.

“Right now all of us here just want to get back to our homes. It’s difficult to try and explain,” Sabraw said.

Sabraw’s experiences encompass the wild, uncontrollable aspect of fire that will never cease to terrorize, confuse, and destroy.

“It’s almost eerie how fire picks and chooses its targets, where it’s going to go and what it’s going to do,” Sabraw said.[vimeo id=”https://vimeo.com/141847047″ size=”small” align=”right”]

“In one spot sat a relatively new ford pickup burned to the ground, nothing left. Melted wheels and everything. Right

beside it was a backhoe… the flames didn’t even touch the tires, didn’t touch the paint.”

For Sabraw, life in the evacuation site was an emotional rollercoaster.

“The first few days here were interesting, sort of an adventure,” Sabraw said. “But then after a while you settle into this sort of dull routine and realize that you really don’t have too much control over anything you do.”

He said this dependency on others was a challenging adjustment.

Once he returns home, he said he will continue to do whatever he can to help the people who weren’t as lucky as he was.

“I’m going to help my friends rebuild best I possibly can. Do whatever I can do to help them,” Sabraw said. “Sort of the country way of doing things. You band together, pull together, just get ‘er done.”

A Teacher’s Loss

“They are trying to have some sense of normalcy, but it’s hard when they aren’t in their house, they aren’t in school, and they don’t see the people they usually do on a daily basis.”

– Autumn Duarte

[vimeo id=”https://vimeo.com/141912144″ w=1000&h=800]

Autumn Duarte is surrounded by her students and a basket of art supplies. As she describes her own tale of the fire, her students paint swirling streaks of red and orange on their papers, depicting their views of the fire that raged just miles away.

Ever since her home was destroyed by the flames, Duarte, a first-grade school teacher, has visited the Calistoga evacuation camp every evening to spend time with former students who also lost their homes to the fire. Her experience is one of tragedy, but also of resilience.

As the fire grew close to her Middletown home, Duarte and her husband grabbed the family’s five pets, some clothes, and fled. The couple spent several nights at a nearby community college before hearing Tuesday night that somebody had seen their home still standing.

But Duarte’s joy was short-lived. The next morning she received a call that the fire had spread overnight and her house was burned to the ground.

“It was very devastating for us,” Duarte said. “My husband and I have our pets, but everything else is gone.”

As soon as she heard about the loss of her home, Duarte, who is not staying at the camp, returned to the evacuation site to be with former students––every night she went to the fairgrounds to read, draw, and spend time with them. For Duarte, this was her coping mechanism.[vimeo id=”https://vimeo.com/141930740″ size=”small” align=”right”]

“Coming here in the evenings, it’s not only for them, it’s for me too,” Duarte said. “That’s where I can forget about my own problems, where I’m going to live now. I can forget about that for a while because we are all kind of experiencing that.”

Not all of Duarte’s students lost their homes in the fire, but according to Duarte, every student knows someone who was affected, and felt the pain and the heartbreak of their friends and families.

“For the Middletown kids, for instance, their lives are totally different,” Duarte said. “They are trying to have some sense of normalcy, but it’s hard when they aren’t in their house, they aren’t in school and they don’t see the people they usually do on a daily basis.”

Normality may be difficult to come by in a community that has been ravaged and destroyed. But Duarte, who continues to help others despite her own tragic losses, is trying to do what she can to ease the communal pain.

Home Away From the Rubble

“You couldn’t have a better place if you can’t be at home.”

– S. Merch Royce

[vimeo id=”https://vimeo.com/141962292″ size=”large” align=”right”]

Mickey Thibodeau sits in a wheelchair beside S. Merch Royce, a friend from Middletown, where Thibodeau’s home once stood. A small dog, who Merch Royce introduces as Frito, yaps inside of Royce’s recreational vehicle, where the two have been living since they evacuated their homes. They are surrounded by an assortment of bright tents and drab RVs parked on a dying grass field, the makings of the Calistoga evacuation camp.

Despite their current situation, the two said they are pleased with the sense of community and hospitality at the Calistoga evacuation camp. In fact, each described the camp as a safe haven of sorts, a temporary home.

“What a fantastic group of people here,” Thibodeau said. “Anything you need, people going around giving out food, asking if you need anything.”

Thibodeau was the first of the pair to evacuate his home. He said the only thing that could have survived the flames was an old backhoe that he had parked in a dirt field.

“I came out of the house at around 4, saw all the wind blowing smoke. My neighbor said the town had been told to evacuate,” Thibodeau said. “I filled the water tank in the RV… got everything ready to leave. By the time I was done, I could see flames about a couple of thousand feet away. I said it was time to go.”

Thibodeau drove to the home of Merch Royce, just one mile from the county line, where many of Merch Royce’s other friends had also decided to convene.

“There must have been 10 or 12 vehicles, motor homes, and a couple of people who knew me, and they all thought they were safe there,” Merch Royce said.

Thibodeau stayed at Merch Royce’s home until midnight, when they were notified that the evacuation zone had been expanded to include Merch Royce’s home. As a result, Thibodeau and Merch Royce decided to drive south, where they stumbled upon the Napa Fairgrounds evacuation site in Calistoga.

“When we got to the fairgrounds, [which wasn’t] until after midnight, the [fairground volunteers] were waiting for us,” Merch Royce said.

Since then, the evacuation site has become a second home for the pair, who praised the kind staff, the ability to easily receive necessities, and the great food.

Merch Royce has been volunteering at a laundromat, washing clothes for the evacuees.

“I’m evacuated and I’m helping other people do their clothes and it’s awesome,” Merch Royce said. “Everybody is so grateful, everybody is so nice. People here are dealing with the disaster just perfectly.”

For Thibodeau and Merch Royce, the evacuation camp has provided them with unexpected hospitality in the face of loss and uncertainty.

“You couldn’t have a better place if you can’t be at home,” Merch Royce said.

A Volunteer and Her “Family”

“If we can give them any kind of comfort or any kind of assistance to help them through, that’s what we’ve got to do. It’s what we would want for us.”

– Elly Galindo

Elly Galindo pauses to help an elderly couple whose house was destroyed. She is helping them find a place to stay, and after making a few phone calls, Galindo tells the couple she has found them a hotel room for the week.

As a member of the Calistoga Athletic Boosters and a leader of the Napa Fairgrounds snack shack, Galindo has a different connection to the Valley Fire: Instead of a victim, she is a volunteer.

When she heard that the Napa Fairgrounds in Calistoga would be used as a primary evacuation site for the victims of the Valley Fire, Galindo and local volunteers began to cook. According to Galindo, the camp kitchen collaborated with the Red Cross and served nearly 1,500 meals a day to the evacuees.

“They are people who have lost everything,” Galindo said. “They’ve come to a point where they can have a cup of coffee and stand and talk with you in the morning about the fact that everything they’ve ever owned is gone. It is utterly humbling and emotional.”

Galindo did not lose anything in the fire, but she said she feels a strong connection to those at the fairground who did, like her daughter’s soccer coach and some volleyball players she used to coach.

“It feels like a big family and we have to take care of each other,” Galindo said. “These people are sleeping on the ground in someone’s else’s clothes. They don’t have anything… and they have to start all over. They don’t know where they go from here––not knowing has got to be a horrible feeling.”

High winds, dry ground put Marin County at fire risk

By Andrew Hout and Keely Jenkins

Burning 76,000 acres at its peak, the Valley Fire flew across dehydrated land, edged on by 25-mile-per-hour winds. The third most devastating fire in California’s history, the Valley Fire has destroyed approximately 2,000 homes in Lake County, injured four firefighters, and killed four citizens. Fires have been numerous throughout the summer and despite being alleviated from the drought, Marin remains at a high fire risk.

Marin’s vulnerability to large fires is prompted by record-breaking drought conditions, all of which have caused the Marin County fire department to consider Marin to be at a high fire risk. With an Indian summer creating a hotter climate and drying vegetation, aspects of the Valley Fire could repeat themselves here in Marin County, under the right weather conditions, according to Larkspur Fire Captain Tom Timmer.

“The winds come off the valley, off Sacramento; they’re all offshore so they push the fog out into the ocean and the wind decreases. That’s when the fuels dry out,” Timmer said.

If a vegetation fire like the Valley Fire were to occur in Marin County, a high population density along with the small, one-way roads in areas such as Ross would lead to utter disaster, according to Kelly Maurer, a Valley Fire victim who previously worked at Marin General as a trauma nurse.

Maurer, whose son and daughter were in the vehicle with her, drove across a golf course and through a wall of fire in order to escape the flames. She was among multiple residents of Lake County who experienced panic and traffic congestion because of the last-minute notices to evacuate their homes. The speed and ferocity of the fire forced those fleeing to be hasty. Many residents did not have enough time to grab pets and important belongings.

This disorganization could be observed in Marin, as 54.5 percent of Redwood students have a precautionary evacuation plan according to a September 2015 Bark survey.

“A lot of people wait until the last minute to evacuate, which is extremely dangerous. You should never try to do that. You should never try to save your home,” said Fernando Herrera, a Captain with Cal Fire who was stationed at the evacuation center at the Napa Fairgrounds.

“We heard stories of people waiting until the last minute. Luckily they were able to make it down to a safe area, but then there are probably a lot of people who didn’t make it,” Herrera said.

Timmer also emphasized the importance of not procrastinating when evacuating from a fire. Maurer said it interferes with the firefighters trying to battle the flames and jeopardizes the safety of the people.

“If there’s a fire anywhere near, just grab all your stuff and get it in the car and just go. Don’t wait for evacuation notices––we didn’t get one,” Maurer said.

Citizens can perform a number of safety measures to protect their homes, like watering down their houses and clearing the surrounding bushes, according to Herrera and Timmer. One 75-year-old Middletown resident, Roy Sabraw, immediately took action to save his house when he received news of the fire.

“A friend and I at the ranch were up quite late Saturday night cutting the firebreak out in the back pasture and hosing down the buildings until we had to leave at about 11 o’clock when the electricity went out and we had no more water pressure,” Sabraw said. “I’ve found that our houses are still standing, thanks to our efforts Saturday night. We have a home to go back to.”

In the Lake County area, many patches of houses were completely burned to the ground, while others in the middle of the fire’s path were unscathed. The burned areas look like they’ve been demolished by bombs, with possessions barely detectable among the ashes.

“When you go to town now, a friend’s house will be standing in the middle of the block [with] no damage at all, but everything around it is gone,” Sabraw said. “It’s almost eerie how the fire picks and chooses its targets, where it’s going to go and what it’s going to do.”

Herrera recommended Sabraw’s prevention methods and listed a number of other precautions homeowners should take. Among other precautions, residents can trim trees away from roofs, remove dry shrubbery from the perimeters of houses, move propane tanks at least 30 feet, and keep gutters clean, according to Herrera.

Marin County’s susceptibility to fires is apparent when looking into the past of the Bay Area. In 1991, the Tunnel Fire in the Oakland Hills consumed 3,469 homes, 2,000 vehicles, and 25 lives, making it the worst fire to burn in California, according to Cal Fire. The fire, which was spurred on by winds, occurred just across the bay. Taking place during the middle of a 6 year drought, which lasted from 1987-1992, rainfall levels fell to fewer than 40 inches, according to the Marin Municipal Water District.

“We have similar topography to that. We have similar areas, but it’s all about the weather and the right condition so hopefully that will never happen,” Timmer said.