Hearts, lungs, neurons: all essential to life, all irreplaceable –– until now.

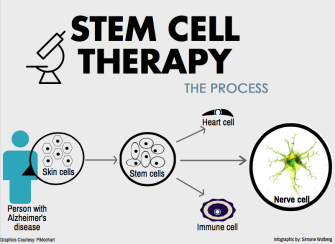

Known as “master cells,” stem cells may hold the key to tissue regeneration, organ replacement, and disease prevention, according to recent research from local labs.

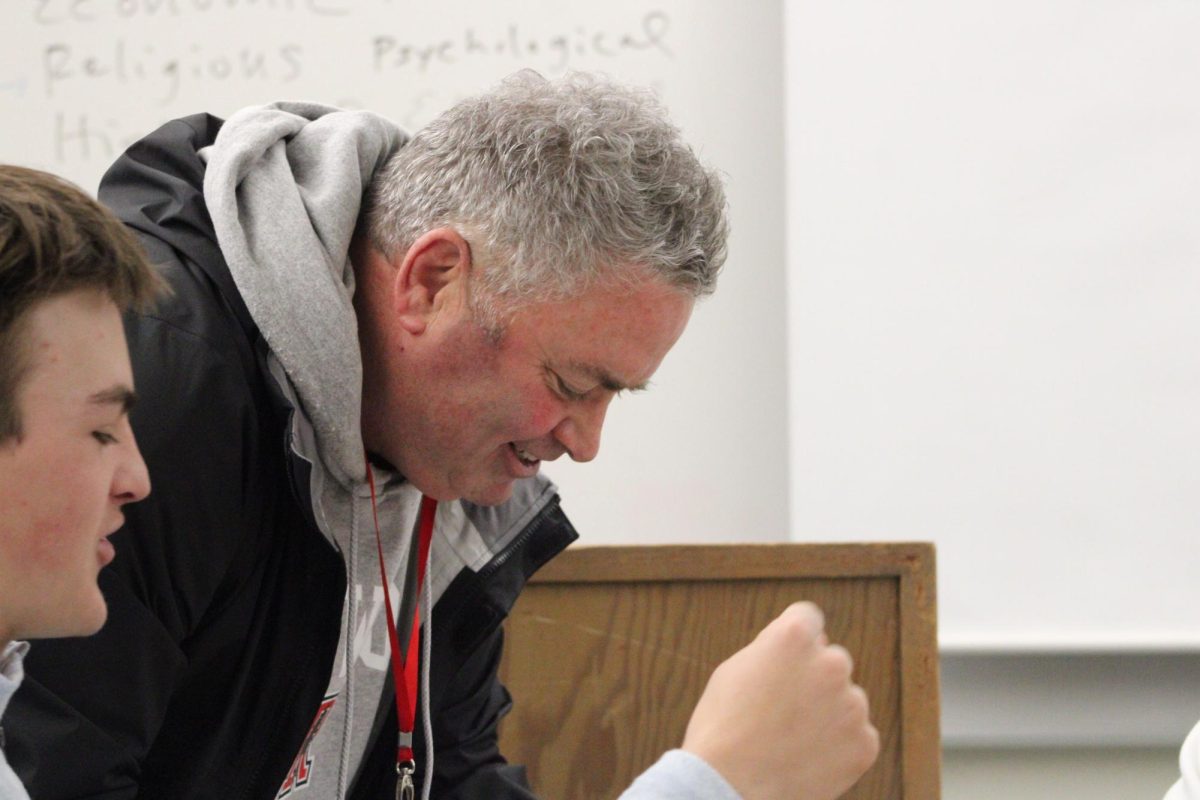

Greer Gurewitz, Redwood alumna and biochemistry major at Washington University in St. Louis, sees the benefits of stem cells.

“Stem cells are really the state zero of cells. They can be induced and made into any other type of cell,” Gurewitz said. “The whole point of regenerative medicine is that cells can go back in the body, replace unhealthy cells, and thereby cure disease.”

As an intern for the Buck Institute, a Novato-based center for aging research, Gurewitz saw “master cells” at work. Findings from the Buck’s Zeng, Ellerby, and Jasper labs, along with data from its new stem cell bank, the largest in the world, help further this medical frontier.

Dr. Xianmin Zeng, head of the Zeng lab at the Buck Institute, hopes to cure Parkinson’s disease with the help of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). iPSCs are adult cells that have been genetically reprogrammed to an embryonic stem cell–like state.

“My lab uses pluripotent stem cells to generate neurons lost to Parkinson’s disease,” Zeng said. “The hope is that these nerve cells will function as normal dopamine-producing neurons.”

By replenishing dopamine levels in the brain, it is expected that patients will recover motor functions lost to Parkinson’s disease.

Zeng’s lab is currently using its own perfected methods to modify its nerve cell preparations for possible human treatments, such as cell replacement therapy.

Huntington’s disease, another neurodegenerative disorder that inhibits movement, may also be cured through iPSCs, the Buck Institute postulates.

Gurewitz assisted in testing this hypothesis during her internship at the Ellerby lab her senior year. The Ellerby lab is replacing neurons damaged by Huntington’s disease with healthy neurons derived from pluripotent stem cells.

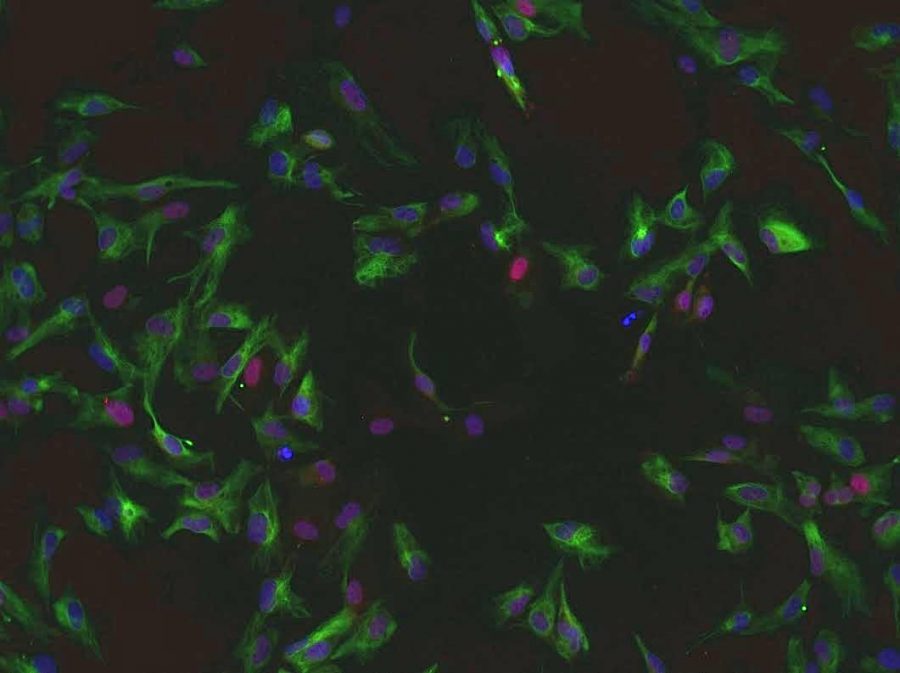

“I stained iPSCs and analyzed them through special computer programs during the week of my internship,” Gurewitz said. “Staining stem cells is a lot harder than it seems. They come in a dehydrated form so you first have to hydrate them, then discern the different regions within the cell, and then stain correctly.”

After Gurewitz stained the slides, the neuronal stem cells were analyzed for Huntington’s disease under a microscope.

Not only are specific diseases in study, but so are greater relationships. In the Buck Institute’s Jasper Lab, head researcher Dr. Heinrich Jasper is exploring the link between stem cells and aging.

According to Jasper, stem cells stop functioning due to damage within the cell or altered conditions within the aging body. Each type of stem cell degenerates differently with age.

“There are stem cells in the intestine, the skin, the blood system, etc. All of these stem cells tend to behave differently with age,” Jasper said. “For example, in the blood system we see a lot of stem cells become hyperactive and actually become skewed in shape, so that they differentiate into the wrong type of cell. This leads to dysfunction.”

Jasper is studying ways to prevent such dysfunction in flies. He is specifically monitoring the effect of intestinal stem cell conditions on the overall health of flies.

“We have found ways to improve how the flies absorb nutrients by manipulating certain genes within their intestinal stem cells,” Jasper said. “We can essentially bring the fly’s tissues back to a more youthful state, improving their metabolic health.”

While these efforts and results are promising, Jasper believes it will be a while before stem cell technologies are perfected.

“Stem cell therapy, the use of stem cells to treat or prevent disease, is already in practice. It has potential, but I think it will take another decade until it is used on a large scale,” Jasper said. “Stem cells, if wrongly prepared, can turn cancerous. We must solve these problems before we use stem cells to repair major organ tissues.”