Although some students may see President Barack Obama’s recent decision to relax the embargo on Cuba as no more than an opportunity for a potential spring break trip, the change in United States policy and subsequent attention on Cuba has larger significance for many Cuban-Americans, including Spanish teacher Gilda Obrador and English teacher Catherine Marsh.

On Dec. 17, Obama announced plans to normalize diplomatic ties with Cuba after more than 50 years of an economic embargo on the country. The embargo did not allow Cuban citizens to have any commercial, financial, or economic relations with the United States. As of Jan. 16, U.S. citizens are allowed to travel to Cuba if they meet one of 12 criteria, which include family visits, government work, journalistic activity, professional research, and educational or religious activity. The Obama Administration also re-established trade relations with the island nation.

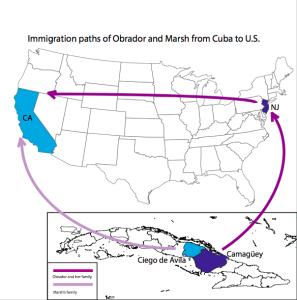

When Obrador was 14 years old, she and her family immigrated to the United States from Camagüey, Cuba under the Family Unity Act, which allowed Cubans with American relatives to immigrate to the United States. Obrador’s aunt on her father’s side was their key to U.S. residency.

Although her family did not speak much English, Obrador said they came to the United States because they thought it would offer more opportunities.

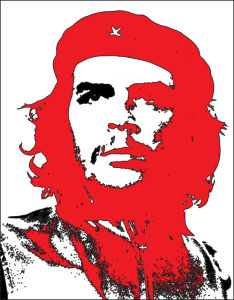

“Because Cuba is a communist country and has had a dictator for over 50 years, it was not the best place to grow up or to stay in,” Obrador said. “My parents knew that the U.S. was the better place for their children to grow up, go to school, and to decide what they wanted to be versus having a government dictate what they should be and how far they could go in life.”

She said that when she arrived in the United States, she was surprised by the cultural diversity.

“Coming from an island, I had never heard that many languages. I had never heard that many accents,” Obrador said. “When I spoke Spanish, other Spanish speakers could recognize that I was Cuban. I had a realization that there was a whole world out there. Cubans are so sheltered and the government doesn’t really let you have an outlook on what’s outside of the island. It was an awakening.”

Obrador said that when she heard Obama’s announcement about the upcoming policy change with Cuba, she was happy, yet skeptical that it would make a real impact on the Cuban people.

“It’s hard to make a deal with dictators. They change their minds right away,” Obrador said. “They really don’t care about breaking deals and who that will affect. Once I see it, I will believe it.”

She said that if the change in policy follows through, she believes Cubans will certainly benefit from a greater global perspective, but it will take some time for Cuba to become strong enough to compete with other superpowers.

“I think that at least Cubans will have access to seeing other people in the world, talking to people who have different ideas, hearing about another way of life and different types of government,” Obrador said.

Currently, the Cuban government owns and controls all broadcast media and prohibits private ownership of electronic media. The government operates four national TV networks and many local TV stations, six national radio networks, an international station, and many local radio stations. According to a 2014 article published by the Washington Post, only about five percent of the Cuban population can access the full global Internet, often through government institutions, high-end hotels, or black market access.

Obrador said that when she was growing up in Cuba, she didn’t know there was an embargo because she had never known another way of life. Regardless of the political dictatorship, she said she looks back fondly on her time growing up, but admitted that her parents might have a different viewpoint.

“I didn’t think much of it. You’re not taught to think and to question the government. You’re only taught to accept and survive,” Obrador said of the embargo. “I had a happy childhood. Whatever my parents had to struggle with to put food on the table, I had no idea.”

Obrador said that she identifies as Cuban-American because the two cultures have each played a different role in shaping her current identity.

“I eat Cuban food, I listen to Cuban music, I dance Salsa, I do Cuban traditions on New Year’s Eve with my husband, and we want to raise our child with those traditions,” Obrador said. “I’m not limited to only those Cuban traditions though. I do Thanksgiving and I celebrate the Fourth of July. We’re a mix of the two cultures because we feel we’re both.”

Five years after she moved to the United States, Obrador visited Cuba for the first time, an experience she described as bittersweet because while it was great to see her friends and family, she felt as though she was missing out on being part of their lives. She became teary-eyed as she recalled the last time she saw her grandparents.

“I was happy to see the people I grew up with, my friends, the grandparents on my father’s side I grew up with––that was the last time I saw them together because they were old and they passed away,” Obrador said. “Life continues, you don’t stop and it was a very special trip for me and my sister. That’s the hard part about immigration. I’ve been there and it’s a give and take.”

However, Obrador said that she never regretted moving away because the government was so repressive, and living and being able to raise her child in a land of greater opportunity was more important to her.

“If [leaving] meant giving up my family, then it was worth the risk,” she said. “My son was born in a free country, so I think that’s worth the separation.”

She said that some people, generally the older generations, who immigrated to the U.S. from Cuba do not support lifting the embargo. They oppose travel to Cuba, and sending money to relatives because these all support the country economically. They do not want to associate themselves with Cuba because of what they endured under Fidel Castro, the longtime communist political leader of Cuba.

“I cannot punish my family for a political fight I’m not going to win,” Obrador said. “Yes, we are divided, but the younger ones, we want change.”

Like Obrador, Marsh grew up in a Cuban household, but in Burbank, California, where a fairly large Cuban population resides. She lived with her mother, a U.S. citizen by stroke of luck—she was born in New York due to her father’s import/export business—and immigrant grandmother, whom she called “Abuelita.”

Although she has never been to Cuba, Marsh still practices Cuban traditions with her children.

“When I was growing up I was in a comparsa, a Cuban dance troupe, and the pride and love for Cuba was always huge in those days,” Marsh said. “We had awesome New Year’s Eve parties where we put 12 grapes in our mouths and threw a bucket of water out of our front door. There’s a lot of wonderful Cuban traditions that I grew up with and still do today.”

Marsh added that many of her family members who have traveled to Cuba said it was emotionally difficult to see because it looks the same as it did when they left.

“A couple family members have gone back and it’s been pretty dismal for them because it hasn’t aged,” she said. “My mom tells me stories of when she went back and about how she’d get a cab and it would break down and they had to walk, or they were waiting for a bus that never came. Bicycles were really the best form of transportation because they could easily fix them.”

However, Marsh also said that many of her Cuban friends enjoy visiting Cuba.

“I’ve had several friends go [to Cuba] and they love it —they’re completely enamored with it. It’s this little pearl in the middle of the Caribbean that has not been touched for a very long time,” she said.

Marsh said that one of the more prominent reasons she has yet to visit is because of her grandmother’s bad memories of her time there under Castro.

“My grandmother endured a lot of things under Castro’s regime. Everything was basically taken away from them,” she said. “We sort of made a promise to her that we wouldn’t go until Castro fell, and no one believed he would last as long as he did.”

Yet Marsh said that because her family has lived in the United States for so long, the promise they made has since expired.

“It outgrew its authenticity and Abuelita even said, ‘You should go and you should see where we lived and the island.’ Even though her memories were marred in that decade with feeling always watched and never safe, she still has really beautiful recollections of her time in Cuba,” Marsh said.

Marsh said that although she never lived in Cuba, she witnessed the effects of the embargo on other Cuban-Americans. She recalls that her family used to frequent a Cuban restaurant, where they’d give an envelope of money to a waitress who would deliver it to her relatives in Cuba. Marsh said that the money was then used by her family members to buy basic necessities in the Cuban black market.

“At the time, the black market was available to you, so if you had money, you could go buy your soap, or you could go buy your toothpaste or your shampoo for your hair and things like that,” Marsh said.

She added that Cubans need many items that the average American takes for granted.

“People who have gone to Cuba tell me that when they visit, they come back with an empty suitcase because they’ve left their shampoo, they’ve left their toiletries, they left their tennis shoes, T-shirts, things like that, because those are the things you can’t really buy,” Marsh said. “[In America], we get to go anywhere and buy as many shoes as we want, as many T-shirts as we want. It’s limitless. There’s a lot of freedom for us.”

However, Marsh said that although the embargo had negative effects on many Cuban-American families, she believes it was necessary to have at that time.

“[The embargo] was established at a time that I think was necessary, when Cuba was a sincere threat to the United States,” she said. “Over time, it was something that was kept in place because of a perceived threat and now that threat is sort of gone, I am glad it’s over or being modified.”