Two years ago, the patch of grass between the pool and the amphitheater was just that: a patch of grass, sometimes used as a viewing area for parents as they watched their chlorine-soaked children on Saturday mornings during summer league swim meets. A year later, the parents have been replaced by students kneeling in damp soil as they pull weeds from flourishing garden beds.

Science teacher Joe Stewart started the sustainable, organic farm in this area in September of 2013 after the TUHSD School Board reserved the land adjacent to the ecology garden. The quarter-acre that was once used as a resting place during swim meets now thrives with fresh soil and blooming vegetation.

The ecology garden, a small planting area next to the Redwood pool, founded by Stewart in 1997 that Ecology students use sporadically to learn about the plant cycle, helped spark the idea for the current sustainable farm, which is used by a larger group of people and serves the purpose of teaching students about the food production process.

“Students really loved [the ecology garden],” Stewart said. “It wasn’t the focus of what we did in [Ecology] class, but it was a very strong support. It was an experimental garden.”

Stewart explained that, after working in the garden, students were interested in extending beyond agricultural experimentation and wanted to see the the production side of farming first-hand to help them understand the significance and impact of food production.

With the help of volunteers from the community, Stewart was able to build half of the sustainable farm over the course of several work days last school year and over the summer.

In addition to the farm, Stewart began teaching a Sustainable Agriculture class at Redwood this school year. The two sections of his class and the additional students who volunteer at the monthly community work days have helped build and maintain the farm, which is almost complete.

Stewart stated that the class follows the same motto as the new farm: “Growing sustainability through science, action, and community.”

“Basically what we’re doing is learning how to do agriculture in a sustainable way and why we do agriculture in a sustainable way,” Stewart said. “We’re on the farm about 60 percent of the time actually doing what we’re learning about and learning what we’re doing, and then we’re in class about 40 percent of the time getting a deeper understanding of the science behind what’s going on in the farm.”

The class is split up into separate groups based off of a monthly rotation, in which all the students take turns managing different aspects of the food production process, according to junior Dana Brooks.

The watering group handles the irrigation system, the harvesting group harvests the crops and sells them at farmers’ markets, the building group improves and maintains the farm’s infrastructure, the compost group manages the farm’s compost, and the networking group spreads awareness about the class and upcoming events, according to Brooks.

According to Stewart, a major aspect of the farm’s success has been the guidance and support of the non-profit organization Global Student Embassy (GSE), which strives to provide hands-on opportunities for the younger generations to engage in environmental action.

Every Wednesday this school year, Jonathan Kaufman, the GSE Marin Program Coordinator, has taught alongside Stewart, directing various agriculture projects on the farm.

Overall, Stewart said he wants students to feel excited about and and engaged in sustainable agriculture.

“I want them to feel like they’re learning a lot, feel like they have the skills to go on and continue this kind of study and run their own food production in their own backyard or even make a career of it,” Stewart said.

Life on the Farm

Different crops are planted based on season and student interest. In the cooler seasons of fall and winter, students plant crops that grow closer to the ground so the plants don’t have as much exposure to cold weather, according to Stewart.

The farm has a few perennial plants which grow year round, such as strawberries, blueberries and raspberries. These are popular plants that grow within four to six months and then die back and are composted.

According to Stewart, the farm is watered for about an hour a week, which is low for any sort of agricultural system. The organic material produced in the garden acts like a sponge in the soil, thereby reducing the amount of water needed.

Not only does the class grow food producing plants, but that they also focus on growing plants that can be composted to help build the soil.

“At least 60 percent of what were growing is not directly intended to be eaten; it’s rather intended to be grown to help support the ecosystem,” Stewart said.

Kaufman added that plants are classified into three groups based on the amount of nutrients they extract from the soil when harvested: highly extractive, lightly extractive, and donor. While extractive plants take nutrients from the soil, donor plants actually replenish the soil.

The class follows a specific planting rotation based on this classification, according to Kaufman.

“We are going to plant our tomatoes, our eggplants, those things that extract a lot of nutrients,” Kaufman said. “We will plant those, and then we’ll follow that with a plant that does not take as much, like a potato. And then the last thing in that rotation that we will plant, like a legume, that’s fixing nitrogen and giving back to the soil.”

Though plants are the main focus, they aren’t the only living things that inhabit the farm.

“A big part of sustainable agriculture is finding ways to mimic nature, and so that means creating an ecosystem,” Stewart said. “Part of our study is area searches of birds that are present, and there are quite a few species of birds that regularly visit the site.”

House finches, house sparrows, starlings, crows, and seagulls are among the most common species that frequent the farm, Stewart said. Geese are also common, but are considered pests because of their depredation of crops.

Aphids and cucumber beetles are other pests commonly found frequenting the farm, but with help from ladybugs, these populations are minimized.

In addition, according to Stewart, decomposers such as worms thrive beneath the soil by adding nutrients and breaking down organic matter.

“One of the main focuses of what we do in the class is building soil and having a really rich microbial and decomposing ecosystem in the soil,” Stewart said.

The farm does not currently have any large domestic animals.

“As far as large domestic animals like chickens, that’s something that down the road perhaps might come,” Stewart explained. “It will take some planning and advocacy and we’re not quite at that point yet.”

The Harvest

On the farm, harvesting the crops is an ongoing process, especially for the students in the designated harvesting group.

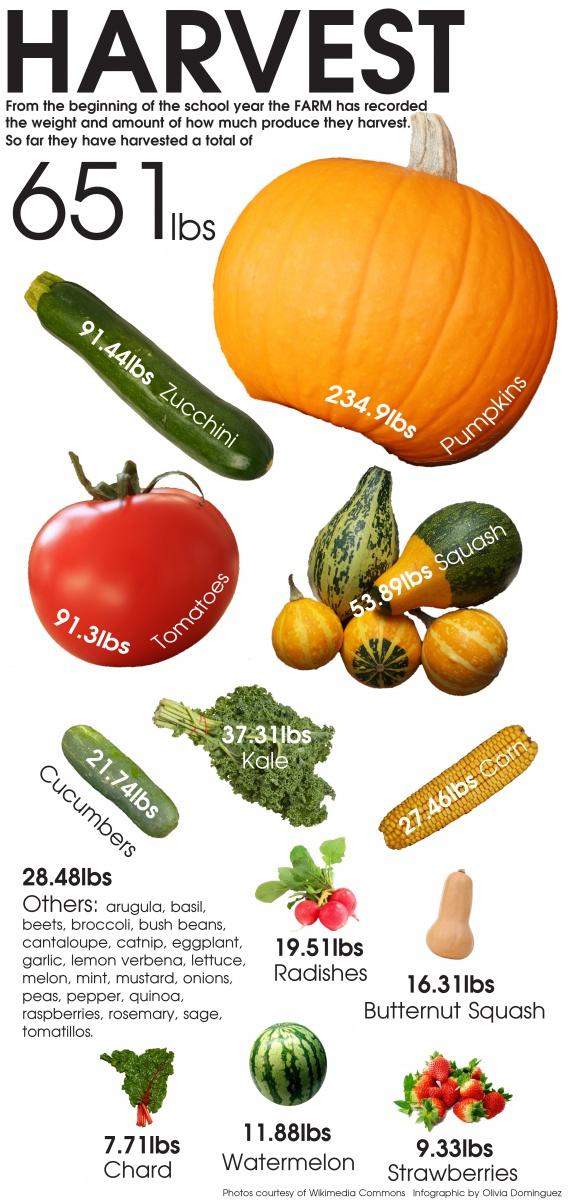

“Everything we harvest we weigh,” Stewart said. “We have a list of what we’ve produced. We’re calculating at a level of whether our outputs are matching our inputs, and that’s part of sustainability.”

In addition, a lot of the crops harvested are saved for the farmers’ markets, which are held on the last Friday of every month from 2:15 to 3:30 p.m., said senior Griffin Wood-Smith, a Sustainable Agriculture student.

“It is a great way to share the wealth,” Wood-Smith said, while working at the late November farmers’ market. “It’s much cheaper than at the stores, there are no pesticides, it’s grown in our farm on our property. And 90 percent of the stuff, other than the dried herbs, we picked today. So, it just is kind of a rewarding feeling.”

The money accumulated from the crops at the farmers’ markets is used to finance new tools, materials, and assistance for the farm, according to Wood-Smith.

Community and farm plans

Community farm days are held on the last Saturday of each month from 10 to 12 p.m. to give anyone interested an opportunity to come and help out with bigger projects on the farm.

On a work day in late November, the class, along with several volunteers, began work on their next big project, the construction of a ShelterLogic greenhouse, which is now structurally complete.

[vimeo id=”https://vimeo.com/117302998″ size=”large”]

According to Kaufman, the final product of the greenhouse will have two rows of beds for winter cultivation, as well as tables on the north-facing side, where seeds will have a chance to grow and mature during the cold winter season.

Other teams of students and volunteers worked on clearing beds, making compost, weeding, planting spinach, arugula, broccoli, and lettuce, and harvesting crops.

At the moment, Stewart is working with a local organization called Next Generation in hope of creating a summer camp led by high schoolers for young students to teach them about sustainability and working on a farm.

“I definitely want to keep building bridges to the community in finding ways to grow the farm and the idea of the farm and maybe even the actual physical footprint of it, so more people can be involved,” Stewart said.

Stewart said that he is happy with the farm’s current size because it keeps the students busy and produces a lot of food for the farmers’ markets, but he is always looking for ways to get more students involved.

According to Kaufman, potential future plans and goals for the farm include the addition of chickens and bees and an overall increase in production.

Implications for the future

The farm is a place where students, teachers, and the entire community can come together over an important issue that is relevant to the entire human species, Stewart said.

“Agriculture is pretty much the way we impact our planet most significantly, and it’s unavoidable —we need to eat to survive — so how can we do that in the most thoughtful way?” Stewart said.

The class not only focuses on the benefits of growing nutritious food, but also on the ways that the farm is helping the environment. For example, Stewart explained how consuming food from the farm can reduce one’s carbon footprint.

“Food on average travels about 1500 miles to get to our plates, but if you grow it here and just drive home a mile or two or ride your bike with it home, then you’re reducing that significantly,” Stewart said.

According to Kaufman, learning how to live sustainably is increasingly becoming the challenge of our generation.

“If we can’t really get our consumption in balance, if we can’t learn how to use only what we need, return nutrients to the earth, and not be extremely extractive in our business practices, then we are going to destroy our homes,” Kaufman said. “It is the very future of humanity.”

He explains that what they do on the organic farm is something practical and hands-on.

“It is empowering for the students, because it is something you can take home and ultimately it is just a model for sustainability,” Kaufman said.

Kaufman said that the most important thing for students to take away from their experience on the farm is the idea that, when they take a radish, beet, or potato from the ground, they are not only taking food for themselves, but they are also taking food from the soil.

“When you take from the Earth like that, you need to give something back. And that, that is sustainability,” Kaufman said. “It’s not just taking, it’s giving back. It is having a relationship with where your food comes from.”