Located over the hills in San Rafael, Marin’s juvenile hall is home to a maximum of 190 detained youth in the county at a time. Juvenile detention and rehabilitation is an alternative to the Marin County Jail for residents under the age of 18 and is a large system with multiple steps that work towards preventing and educating troubled youths who have committed illegal actions. According to a March 2023 Bark survey, 50 percent of students have not been educated on juvenile detention in Marin, showing that this complex organization needs more attention and possible reform.

The Juvenile Justice System in Marin

Within the courtroom of Judge Beverly Wood, an integral component of Marin’s juvenile justice system shapes the futures of minors. Although often overlooked, this stage in Marin’s juvenile justice system manages incarceration, which has a rate of 2.1 minors for every 1,000 — only 0.6 lower than the state average.

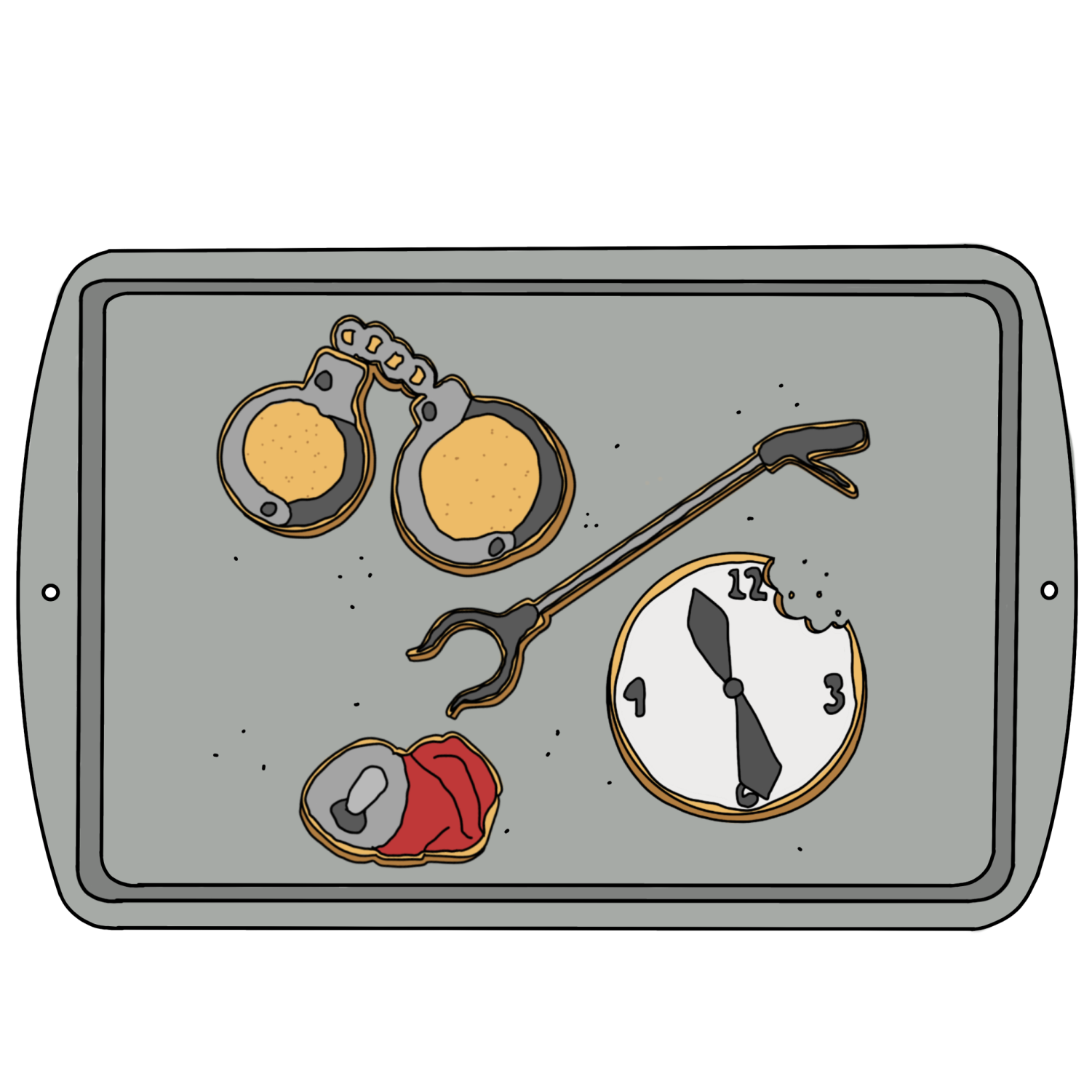

Beyond the courtroom, Marin has adopted a highly individualized rehabilitation system. As a juvenile, minors go to a hearing with a presiding judge, who will decide the consequences. Judge Wood, who has been on the bench for 13 years, is one of these judges and specializes in Marin youth cases. She outlined the multiple levels of rehabilitation Marin offers from divergence — making a construct with the court to live a law-abiding life — to detention centers.

“I have to pick each case individually, I can’t cookie-cutter kids,” Wood said. “Each kid is addressed individually. You always start with the lowest level, and if that doesn’t work, you step it up.”

Along with divergence and juvenile hall, Wood states that other potential rehabilitation methods include becoming a ward of the court (formal probation), community service, enhanced education and/or mental health mentoring. In Marin, Wood acknowledged that the most common cases are drug-related, but even then, there is not a strict regimen to follow.

“Substance abuse is not a straight line, and some of these kids have serious issues; maybe they have had a lot of trauma in their life or predisposition to substance abuse,” Wood said.

Although substance abuse is viewed as a less severe misdemeanor from the court, with repercussions ranging from probation to community service hours, other serious crimes require more severe consequences, such as juvenile hall.

Doubts surrounding the juvenile hall system and its prison-like environment spurred a 2020 announcement by Governor Gavin Newsom of the closure of four youth halls by June 2023, and alternatives — such as camps or minimally restrictive centers — should be arranged. However, Wood claims that these juvenile centers are established for valid reasons.

“There are some very dangerous [kids] out there. One of the things the judicial system has to look at is community safety. … Juvenile hall is secure for a reason,” Wood said. “The idea is you keep [youth] in this secure facility to rehabilitate with the hope that, when they’re done, they can be safe [in the community].”

Additionally, these secure facilities are organized to protect minors from dangerous situations. Each case has different severities which illustrate why the whole system cannot just be dismissed. Although Marin’s juvenile system has made efforts to deal with individual cases, many believe reforms are still necessary and Wood pinpoints her overall goal.

“What we have done in Marin is create a unified court. If I have the juvenile case, I can pull the family case so we can find the root of the problem. … That’s the way to do it,” Wood said. “Juvenile justice works best when everyone works together: kid, parent, probation [officer and] the district attorney.”

Alternative: Youth Transforming Justice

Don Carney is the founder of the Youth Transforming Justice (YTJ) program in Marin, previously known as Youth Court, and a participant in the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Commission in Marin. Through YTJ, Carney offers minors in Marin an alternative to spending time in juvenile hall.

Rather than appearing before a judge, minors who have admitted to smaller crimes — oftentimes involving possession of drugs or alcohol — meet with a group of peers. During this meeting, student volunteers ask the minor specific questions regarding their incident and their life. From the answers the youth provides, the peers are then able to suggest a community service mandate. Once the minor successfully meets the hours and completes a few additional steps, their infraction is removed from their record.

“We are not playing law and order; we are not mimicking the legal system. What we are doing is providing a structure for young people who are troubled, to get support from other young people,” Carney said.

Former Redwood student Aidan Reese went through the Youth Court process after a minor incident with local police. Reese experienced the effectiveness of YTJ and continued to volunteer his time after his allotted community service hours were completed.

“The main goals are primarily to give young people a second chance. The goal is to do restorative justice rather than punitive justice. The focus is on more, ‘Why did you commit these crimes? How could you do something different in the future? Are there contributing factors in your life that should be addressed, that you can do something about and will lead you down a better path?’” Reese said.

To fully complete the YTJ program, the minor must attend and participate in their hearing which also involves the minors’ guardians. The minor will then continue attending hearings, volunteer with the organization and complete any other individualized steps to fulfill the process.

With a 95 percent completion rate and a largely guided process, the majority of kids who enter the program do not relapse, resulting in a recidivism rate of only six percent.

Before beginning the transformative justice program, Carney worked at a Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) focusing on support work for minors who were on probation. During this time, Carney realized that the zero tolerance policy — which automatically expel or suspend students who take part in specific actions, such as smoking at school, regardless of the context or rationale for that behavior — in Marin schools was the main factor causing an overflow of young students into the probation department.

“I had middle schoolers being expelled for dumb s**t and being put in [the juvenile hall] population with some very sophisticated kids who had long criminal histories. … It was disastrous,” Carney said.

In 2004, Carney began YTJ with his YMCA and group home experience in mind, working to create a program that prevented the issues he observed.

“When we started Youth Court, juvenile hall [in Marin] had about 45 beds and generally it was full. Today, the juvenile hall has about six to eight kids in it regularly,” Carney said.

Carney has put immense work into this program which Reese appreciates, recognizing the importance of keeping youth out of the system.

“Making sure that people don’t get caught up in the criminal justice system at a young age [is another goal of YTJ] because … that’s something that can be a really bad cycle,” Reese said. “The goal is to … give [minors] a chance to make the right decisions when they’re younger, and not let the one time they break a rule or make a mistake define them for the rest of their life.”

Missouri Model

The Missouri Model is an alternative method to juvenile detention, which utilizes therapeutic and rehabilitative methods to ensure youths make positive and permanent behavioral changes.

Prior to initial implementation in Missouri in 1974, 70 to 80 percent of juveniles released from youth correctional facilities were reassessed within two or three years. However, the Missouri Model drastically decreased these numbers with a reduced recidivism rate of 8.5 percent.

These methods have entered the Bay Area over the past decade, with the Santa Clara juvenile system now including home-style facilities, individualized treatment and family involvement throughout the treatment. These reforms in Santa Clara generated immediate results with an increase in successful transitions into new communities and a decrease in violence within juvenile facilities.

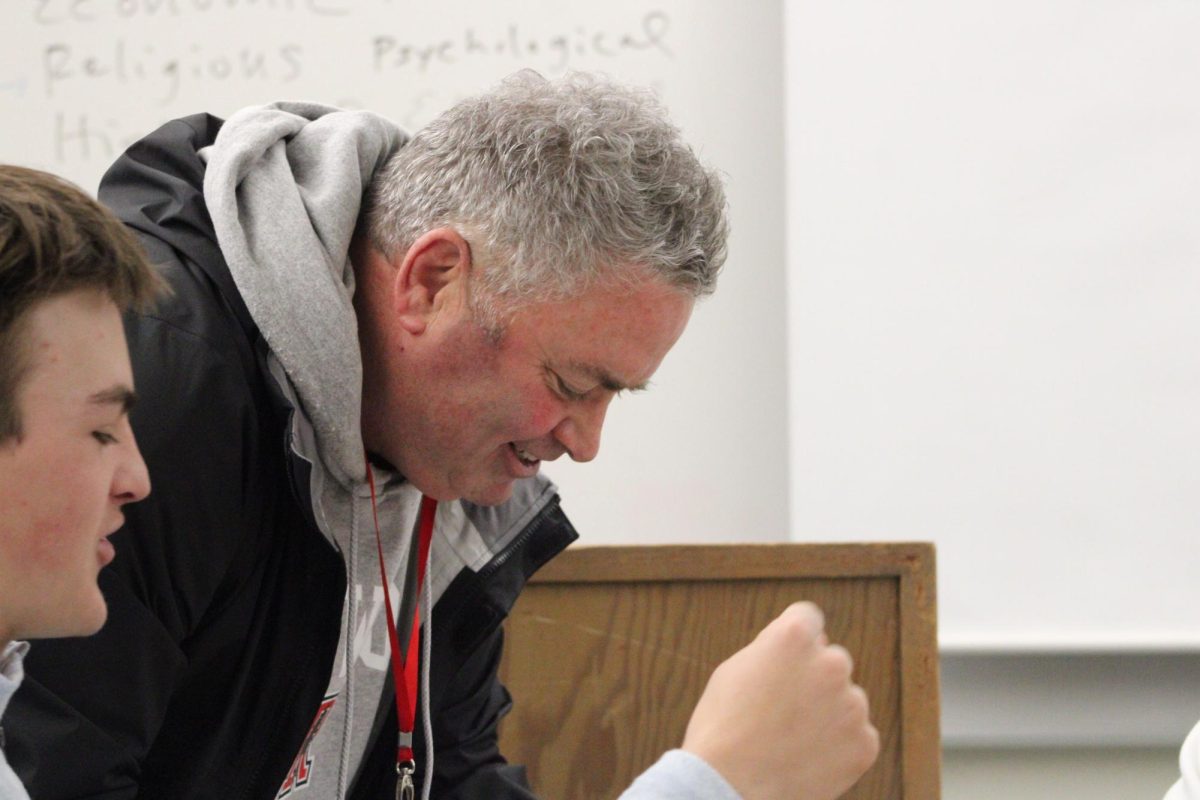

Social studies and street law teacher Jon Hirsch is familiar with Marin’s Juvenile rehabilitation system through his work to help former juvenile hall inmates, and has noticed some of its flaws.

“When you get to a place where there’s a serious offender or someone who doesn’t have a support structure at home, they are lumped together in a way where I worry that they don’t have the kinds of positive role models and influences that they need,” Hirsch said.

When thinking about ways to resolve such issues, Hirsch is an advocate for implementing the Missouri Model in the juvenile hall system countywide.

“The Missouri Model of juvenile justice is something that more states are starting to adopt because of its focus on small groups. Kids are less likely to get lost in the shuffle [with] small groups that are close to home [compared to larger juvenile centers]. [Minors] can have a feeling of community connection, which is extremely important,” Hirsch said.

The guidelines of the Missouri Model ensure that minors in juvenile hall programs are treated as real human beings and rather than being punished, they are given an opportunity to learn from their mistakes. Implementing programs similar to the Missouri Model in Marin, as partially seen in the YTJ, could be an effective option for reform to the system in an individualized and educational way.

Project Avary

Multiple systems, such as YTJ, have developed ways to reshape youth to stop them from recommitting crimes. However, they work with kids who have already participated in illegal activities. Project Avary, a program based in the Bay Area, works to stop the cycle of incarceration by supporting children with incarcerated parents. Natasha Blakely works as an outreach coordinator for Project Avary and recalled how the organization began, dating back to the 90s.

“[Project Avary] started back in 1999 by a chaplain who worked at San Quentin. He saw youth coming in to visit their incarcerated loved ones, and over time, he started to see those same youth being incarcerated themselves,” Blakely said.

Since the program began, it has greatly expanded and works to fight its simple but crucial objectives.

“[Our initiative is] important because there are so many programs for those who have been incarcerated — [enabling] reform and getting help — but usually, the youth don’t have any programs to get the assistance that they need with what they go through,” Blakely said. “A lot of times [minors with incarcerated loved ones] use that stigma to suffer in silence and feel shame for the crimes that their loved ones committed.”

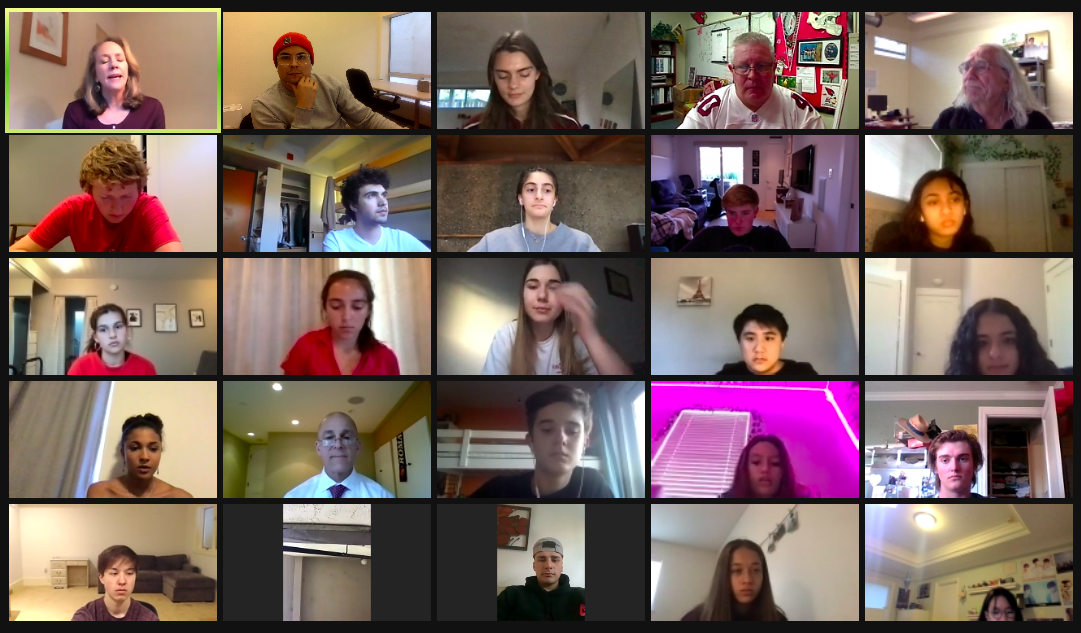

Initially, the program held in-person camps for youth, but moved online due to COVID-19. Although this was a major shift, the company still works to break these stigmas in the minds of youths.

“When [they] see all of your uncles or your siblings who have similar experiences, that’s what [youth] see as their bleak future,” Blakely said. “Project Avary helps [youths] to see that they are not their parents’ mistakes, and they become anything they want. … All of these different activities expose them to so many different things in the world [than] what they’ve experienced at home.”

With firsthand experience, Blakely has learned the importance of growing and finds that healing is rooted in having fun. Project Avary implements this idea in their activities — such as rock climbing, snowboarding and hiking — and works to help kids improve their health and gain confidence while having fun.

“[Having fun] builds community and stronger bonds while providing a place for [youth] to share their experiences, creating a safe zone. We have what’s called ‘real talk,’ where [the kids] can share their experiences judgment free. … Sometimes sensitive topics come up, and we can work with them and make moves according to the situation,” Blakely said.

Visit projectavary.org to learn more about this program, donate or refer a youth with incarcerated loved ones.

From YTJ to the Missouri Model to Project Avary, initiatives around the world are expanding to help new generations stay out of the system and escape the incarceration cycle. Although Marin’s juvenile justice system prides itself on being progressive, it is important to acknowledge areas of growth and improvement as society continues to change and new obstacles arise.