The prevalence of hate symbols and speech is far from new, but with 2020 hate crimes reaching a decade high, their place in society has come under increasing scrutiny. Nationally, disputes over allowing hate speech and symbols in theaters and classrooms has sparked conversations amongst artists, educators and audiences, posing the questions: What qualifies an object or phrase as hateful and where is it acceptable? As this debate continues, identifying hate symbols and speech and understanding their appropriate place in society remains an important task.

Theater

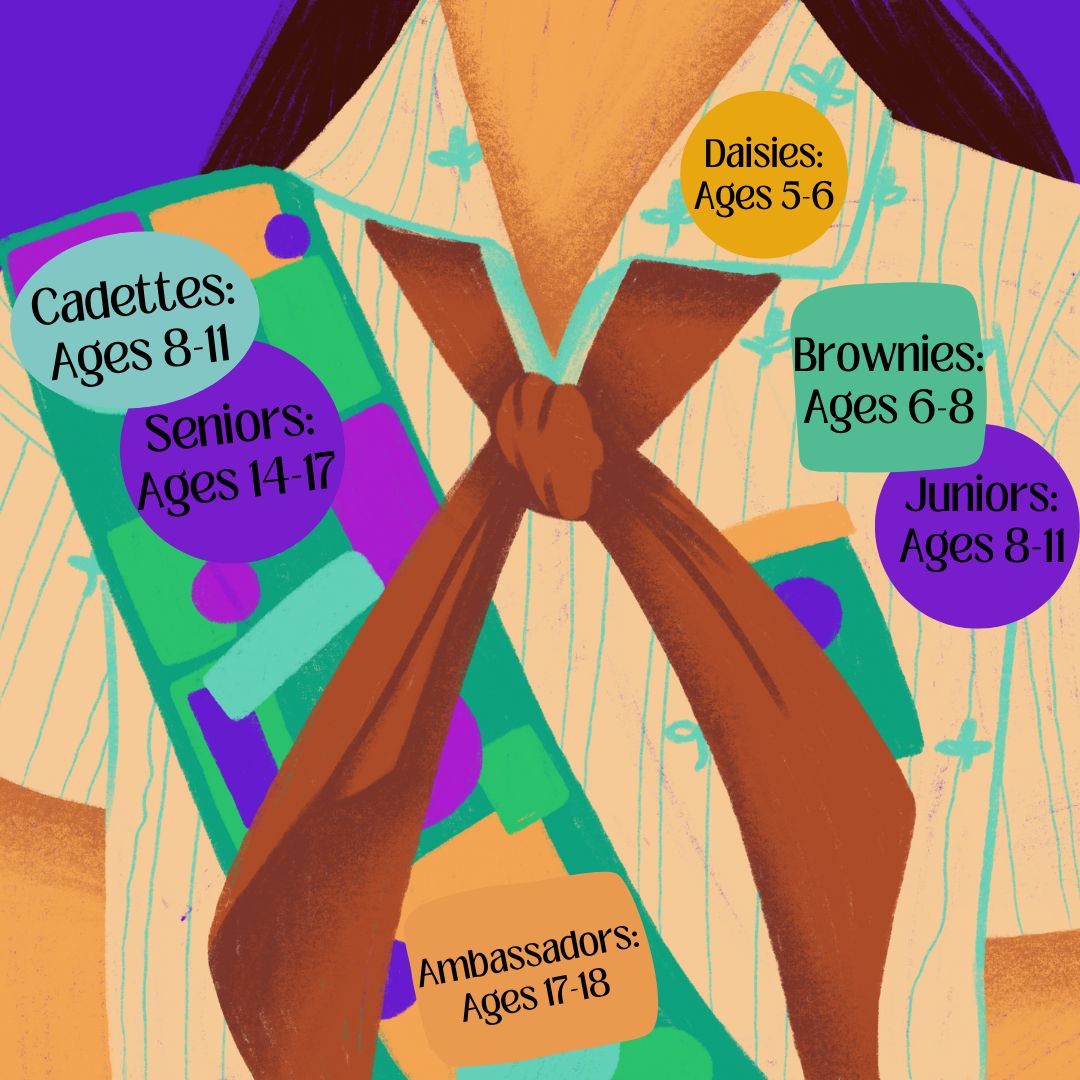

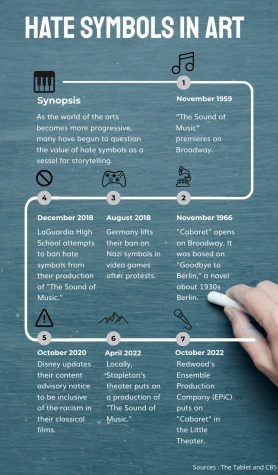

For their winter musical, Redwood’s Ensemble Production Company decided to perform “Cabaret,” a musical set in 1930s Germany. The show tells a love story shattered by the rise of the Nazi Party.

In accordance with the original script’s stage directions, student-actor and sophomore Alexander Berkowitz wore a swastika armband to portray his pro-Nazi character. To avert discomfort, he separated his role from personal beliefs.

“I wasn’t uncomfortable [wearing a swastika] because I understood it’s an act. I was playing a character portraying that [the Nazis] were not good people,” Berkowitz said. “[The play is] supposed to leave the audience thinking: ‘We need to do something about [oppression] … We can’t just stand to the side.’”

In “Cabaret” and other plays about sensitive topics, storytelling is often reliant on hate symbols. “The Sound of Music” famously depicts a family’s journey to escape Nazism, which was recently produced by San Anselmo’s Stapleton School of the Performing Arts. A member of the cast, Morgan Hunt, played the pro-Nazi character, Rolf, and employed similar acting strategies to Berkowitz.

“I had to wear an armband with a swastika on it [and] heil a couple of times, [but] as an actor, when you’re on stage, you’re in a different world. The most uncomfortable parts about it were offstage [when] walking around with my Nazi uniform on,” Hunt said. “It’s [my] job to do things I would never do in real life [to show] the Nazi intrusion into Austria … and that’s the point of ‘The Sound of Music.’”

By associating hate symbols with antagonists, a character’s actions are separated from the play’s morality; Berkowitz attributed part of “Cabaret’s” success to this, as it avoided “rationalizing” the actions of negative characters.

Junior Calla Hollingsworth found this distinction plays an important role in another musical, “Heathers,” which discusses dark issues in a high school setting.

“I don’t condone shouting slurs, but I was playing [the antagonist], Heather Chandler, and she would [shout them],” Hollingsworth said.

Nationwide, however, some schools are taking a different approach. A high school in New York omitted hate symbols from their satirical production of “The Producers,” which mocks the Nazi party and Adolf Hitler. Their superintendent, Bob Pritchard, gave a statement to CBS equating hate symbols in the theater with those etched “on a desk.”

“There is no context in a public high school where a swastika is appropriate,” Pritchard said.

Another New York high school, LaGuardia High School of the Performing Arts, experienced similar conflicts in their production of “The Sound of Music.” Attempts from their administration to exclude all swastikas from the musical were met with strong pushback from actors and parents, limiting their removal to those on costumes.

Aligned with the administration’s efforts, the December Bark survey found that nearly one-in-four students believe hate symbols should never be present in theater productions. Contrary to this perspective, Hunt considers including hate symbols essential to avoiding revisionist and whitewashed storytelling.

“For historical accuracy, [hate symbols] are valuable. In order to accurately portray the danger of fascism, you have to include symbols that were used in terrible ways,” Hunt said.

To fully understand the historical importance of hate symbols, the Redwood “Cabaret” cast, including Berkowitz and Hollingsworth, learned about the history of Nazi Germany.

“We did dramaturgy presentations [that looked into the composition of ‘Cabaret’ to make ourselves] well-versed in the history of the musical,” Hollingsworth said. “It’s important for actors to be informed of their piece before working on it.”

With the perspective Hollingsworth gained in researching “Cabaret,” she found that while there is unease in portraying hateful actions, the message of a piece is incomplete without them.

“While art can [discuss] difficult and harmful topics, it is meant to educate,” Hollingsworth said.

This purpose lies at the core of theater. Thus, hate symbols and speech play much larger roles than simply belonging to costumes, backdrops and dialogues.

Classroom

Beyond theater, the intentional use of hate symbols and speech is also common in classrooms. Hate speech, which the United Nations defines as “offensive discourse targeting a group or an individual based on inherent characteristics (such as race, religion or gender),” is particularly relevant to certain class materials.

English teacher Danielle Kestenbaum formerly co-taught Humanitas, an interdisciplinary course in history and English. In the class, while forms of hate were present in the history portion, students often interacted with hate speech on the literature side. Instead of shying away from works involving such rhetoric, Kestenbaum approached hate speech with a focus on understanding history, which transcends to the other classes she currently instructs.

English teacher Danielle Kestenbaum formerly co-taught Humanitas, an interdisciplinary course in history and English. In the class, while forms of hate were present in the history portion, students often interacted with hate speech on the literature side. Instead of shying away from works involving such rhetoric, Kestenbaum approached hate speech with a focus on understanding history, which transcends to the other classes she currently instructs.

“I approach my classes with honesty and the avoidance of censorship. We only learn when we genuinely learn from the past, [through] horrors, evils and traumas,” Kestenbaum said. “When [classes] look at trauma and tragedy from history, it’s impossible to separate [such events] from the fiction it inspires.”

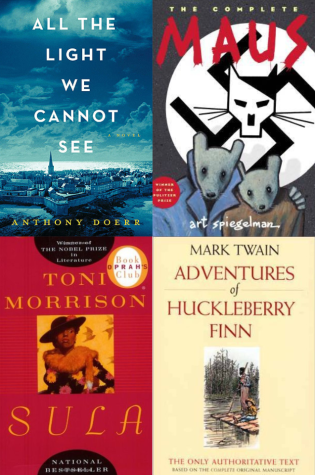

Such “fiction” materializes in plays and historical literature, where the presence of hate speech is notably observable in many books, including “Maus,” “All The Light We Cannot See” and “Sula” — all of which are taught at Redwood. Mark Twain’s “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” which mentions the N-word 219 times, is another book commonly taught in high schools, and its removal was demanded by dozens of parents at a school district in Virginia.

“[By teaching this literature], we are validating that these words are acceptable and they are not acceptable — by no means. We don’t need [the N-word] in the school system,” a parent told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

In Philadelphia, a high school followed through on calls to exclude the book from curriculum, effectively banning it. In the Bark article “Reading into book banning,” Natalie Weber, a librarian at the Marin Civic Center, made the case that students deserve access to all books — even as a record-setting 1,597 books were challenged or banned in 2021.

“In the library world, we believe deeply in intellectual freedom, which means access [to any book] for pleasure or for education,” Weber said.

To achieve this, Kestenbaum finds there is a crossable path between promoting the messages associated with the N-word and teaching lessons that include it.

“In terms of the N-word, I’ve spoken to many different academics and students, some of whom are Black. Some are impacted by the term and think it should never be used, and some see it as a reclamation of empowerment,” Kestenbaum said.

Even with the uncertainty surrounding phrases of hate speech, in Kestenbaum’s class, the N-word is never verbally expressed, and content warnings precede “triggering or traumatic” topics. However, these policies vary with each teacher, and hate speech, including the N-word, has been verbalized by Redwood staff and students for academic reasons.

Even with the uncertainty surrounding phrases of hate speech, in Kestenbaum’s class, the N-word is never verbally expressed, and content warnings precede “triggering or traumatic” topics. However, these policies vary with each teacher, and hate speech, including the N-word, has been verbalized by Redwood staff and students for academic reasons.

Although students rarely opt out of assignments due to excessive discomfort, many still consider content warnings essential to secure learning. According to the December Bark survey, 42 percent of students believe that hate symbols and speech should only be present in art forms with a content warning.

With the appropriate measures, hate symbols and speech in classrooms seek to educate, while not simultaneously promoting negative messages.

In recent years, developments show that proponents of maintaining hateful references look to avoid censorship and whitewashing. Conversely, opponents call for the elimination of hateful content on the grounds that it normalizes harmful ideas. Currently, the purposes and effects of hate symbols and speech, whether on stage or in a classroom, are not fully realized. However, it is clear that the prevalence of hate symbols and speech will not diminish as literature and theater evolve. Considering this, their presence must be employed properly, ensuring that these works fulfill their purpose of educating.