“I really hated myself. It’s very hard to rationalize looking back, but I just had all these negative emotions around myself. I thought that I was lazy. I thought I didn’t work hard enough. I thought I was wasting my potential. I would constantly just yell at myself in my head, ‘You’re such a stupid person,’” said “John,” a college student who grew up in Marin County and requested anonymity.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that suicide is the second leading cause of death for people ages 10-24, and each day, there is an average of 5,400 suicide attempts by students in grades 7-12. Within the halls of Redwood, many high schoolers report similar feelings, as 24 percent of students have experienced suicidal thoughts, according to a March 2021 Bark survey. In Feb. 2021, two Marin County middle school students took their lives within two weeks of each other, and, at the beginning of May, a Novato high schooler also took their life.

This series of suicides points to a conclusion many are uncomfortable admitting: Marin County adolescents are suffering, even before they enter high school. At Redwood, students begin to witness characters suffering from anxiety and depression during sophomore year when Holden from “Catcher in the Rye” becomes part of the curriculum. J.D. Salinger writes, “I felt so lonesome, all of a sudden, I almost wished I was dead.” Many high schoolers value the implementation of curriculum discussing these topics; however, suicidal thoughts can creep up before Salinger has the opportunity to provide students with a character to make them feel less alone.

“I’ve definitely always had elements of anxiety. Depression in general probably began around [age] nine or 10,” John said. “The first time I had objectively suicidal thoughts was around sixth or seventh grade.”

Despite the strikingly young age at which some adolescents are beginning to display symptoms of depression, many are under the impression that talking about suicide puts the idea into the heads of people who were mentally stable beforehand, known as the contagion effect. Due to this notion, many tend to shy away from the topic in students’ younger years. However, Emily Tejani, M.D., a Yale trained and triple board certified psychiatrist with certification in child & adolescent psychiatry, adult psychiatry and addiction medicine, acknowledges the contagion effect’s existence in instances of dramatized media coverage, but disproves the theory in most other cases.

“In general, perhaps always, it’s good to ask about [suicidal thoughts]. Sometimes there’s a fear that talking about suicide may increase the likelihood of a person thinking about it, and the total net of that is not true,” Tejani said. “Even in medical settings, sometimes doctors are a bit reluctant to ask about it, but the research released really shows that asking doesn’t at all increase the risk of attempting suicide.”

Four out of five teens who attempt suicide have given clear warning signs such as changes in behavior, withdrawal from relationships, increasing isolation, lower energy, less future orientation and less interest and excitement around planning for the future, according to the CDC. Tejani stresses that bringing the topic out into the open is one of the ways that a person can support and help a loved one who is either depressed or having suicidal thoughts because it shows the person that someone cares. Furthermore, regardless of a warning sign, discussions on suicide are still necessary as there are instances in which those suffering keep their thoughts hidden, as was the case with John.

“The worst I ever felt was around my junior year of high school. I wasn’t objectively living a negative life. I had decent grades, I had good friends, I had a good amount of accomplishments, etc. But I just have always had really high expectations and I thought I wasn’t living up to them and was beating myself up a lot,” John said. “I would tell myself I was worthless because I f**ked up.”

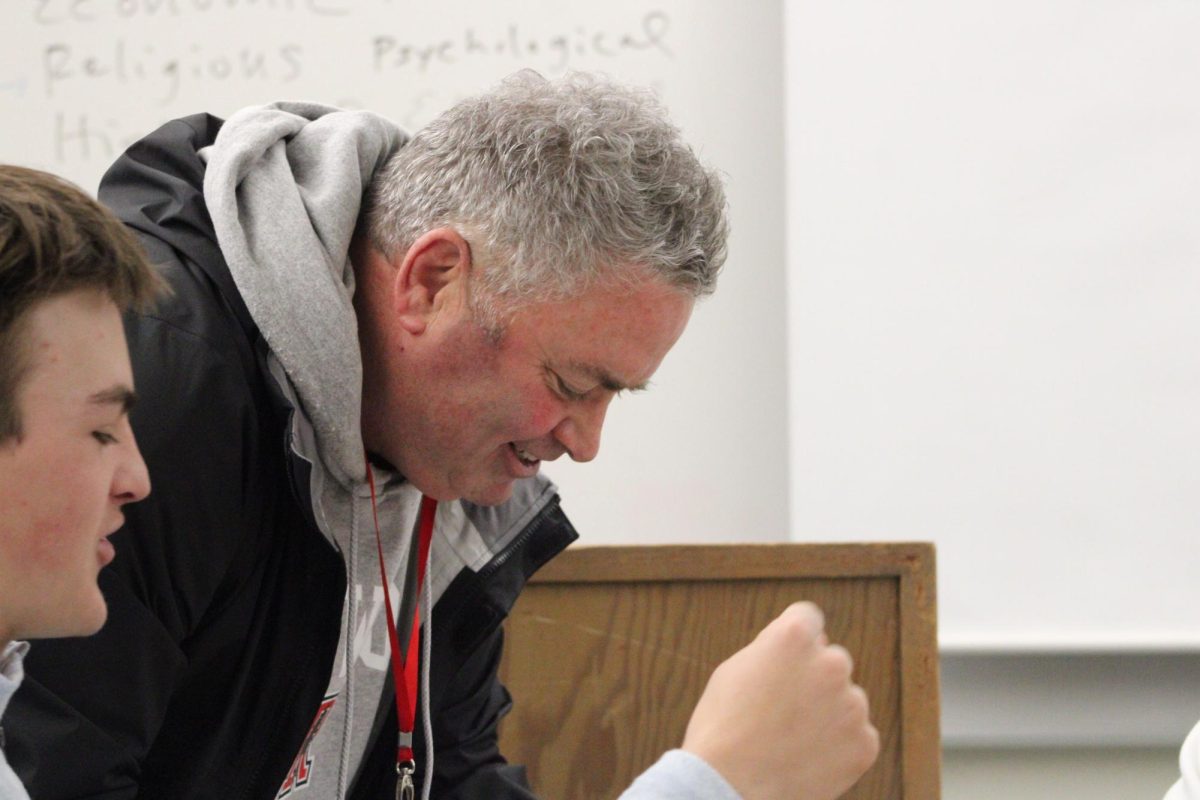

To serve students like John, Emily LaTourrette, an English and AP Research teacher, hopes for the implementation of a curriculum that prioritizes mental health in the coming years.

“As teachers, we’re required to do mandatory [mental health] training each fall and there is a suicide training component,” LaTourette said. “But it’s hard because I think suicide gets bundled in with overall mental health. While our school is really lucky because we have a wellness center, based on my own observations and just listening to students talk, I hear the question, ‘Is what we’re doing actually enough?’”

LaTourrette notes the abundance of resources in place for students, such as the aforementioned Wellness Center and the counseling department, but she is uncertain about students’ willingness to actually utilize them.

“[Seeking help for mental health] isn’t necessarily something that’s been super normalized, and I think that’s not so much a byproduct of our school, but more a byproduct of society as a whole because there’s still a lot of stigma around [mental health] because people don’t really know how to talk about it, especially suicide, so it becomes easy to avoid,” LaTourrette said.

The combination of discomfort from those wanting to help not knowing how to approach tricky conversations and the fear of reaching out by many who are struggling with mental health has led society to a standstill, and those potentially life-saving conversations are left unsaid. Confirming LaTourrette’s sentiments, John notes the difficulties he had with pursuing his own help.

“One of the things that’s really sh**ty about depression is that you think, ‘If I reach out for help, that means that I’m really f**ked because I actually need help,’” John said. “I really did not have a lot of compassion for myself, and that’s definitely something I still struggle with. A lot. Allowing myself to forgive myself.”

Although she highly encourages individuals to seek help, Tejani understands that sometimes more drastic measures need to be taken to save lives in times when people are unable to help themselves. Implementing stricter laws limiting easy access to guns is “perhaps, the single most effective strategy here in the U.S. that we could take, but we really haven’t taken,” according to Tejani. She also encourages putting barriers under bridges and in train crossings.

“Most suicide attempts are a fleeting state of mind,” Tejani said. “The majority of people who survive an attempt are glad to have survived and many do not go on to attempt. [Suicide] can often be an impulsive act, even though there commonly is a period of depression before the events, but the moment at which a person decides to attempt suicide is highly unpredictable.”

In terms of creating change here at Redwood, LaTourrette calls for greater action in shifting the intense culture students are thrust into. The high standards set for students can feel nearly impossible at times, particularly in combination with balancing extracurriculars and family life, LaTourrete notes.

“The demands are really high on our students and there’s a lot of pressure. So sometimes when we have conversations about supporting students, we almost don’t mesh because we can’t necessarily focus on mental health and the wellbeing of students if we’re not going to change or address the cultural challenges that we have that are pushing against that here,” LaTourrette said. “There need to be ways that we are doing things differently beyond offering support to students that isn’t just ‘Hey, we’ve got these resources, go if you want,’ but making it more accessible, more normalized and maybe even bringing it into the curriculum.”

Although stigma surrounding mental health has begun to decline in recent years, there is still progress to be made, as more than half of people who have mental illnesses do not receive treatment for their disorders, according to the American Psychiatric Association. Tejani, John and LaTourrette all share the opinion that receiving professional help does work.

“There are resources, there are supports, there are treatments to getting better,” Tejani said.

John concluded with some parting advice.

“Be kind and forgiving to yourself,” John said. “The world is so sh*t right now there’s no reason to make it sh**tier for yourself by being a d*ck to yourself.”

The Wellness Center at Redwood offers free support during school hours to all students. There are many other free resources, such as the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 800-273-8255, Marin County Psychiatric Emergency Services located in Greenbrae, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration hotline at 1-800-662-HELP, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention at https://afsp.org/ and more that can be utilized if you or a loved one is struggling. If you or someone you know is in danger of hurting themselves or others, please call 911.