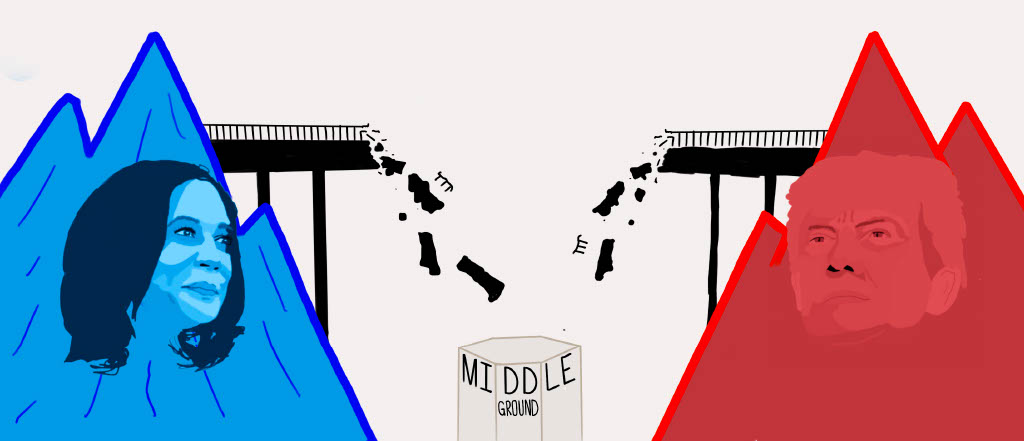

The storming of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 was a colorful sight: rioters clad in varieties of patriotic hues and dark shades composed a sea of stars, stripes and the infrequent animal pelt. Clothing color was one of the few exceptions to the crowd’s general homogeneity, though –– rioters were overwhelmingly white, maskless and falsely asserting that the presidential election had been stolen.

Also on display were several crosses, flags alluding to Jesus and organized prayers, a spectacle demonstrating the prevalence of Christianity at the center of pro-Trump extremism. According to interviews conducted in a Jan. 11 New York Times article, many rioters were self-proclaimed participants in “a kind of holy war:” 40-year-old evangelical Christian Lindsay French told the Times that she jumped on a flight from Texas to Washington, D.C. to attend the president’s rally after receiving an omen from God. Religion has long been alive and well in the U.S., but invoking divine beings in the name of Trump is a fairly recent development –– one that represents a distorted faith sweeping many regions of the country.

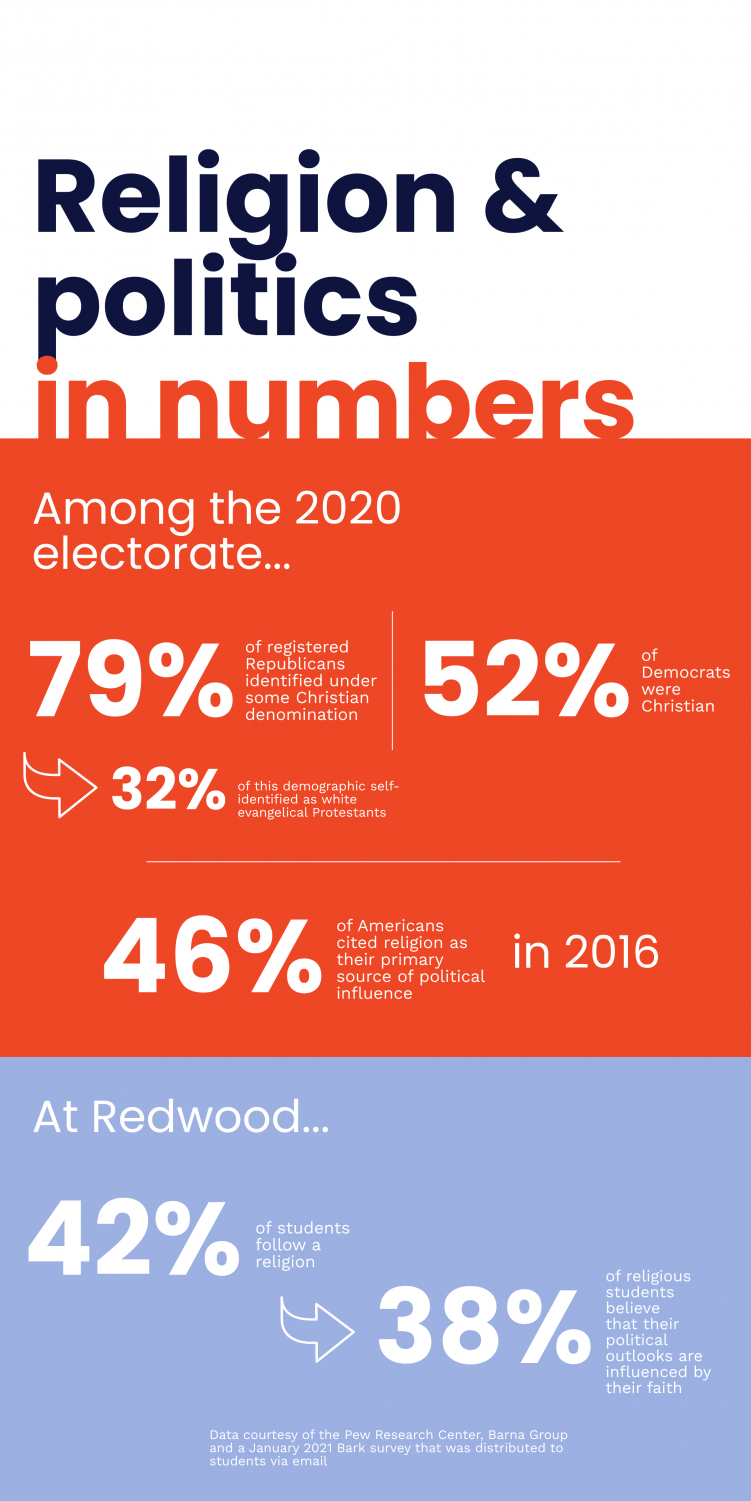

Historically, political conservatism and Christianity have been inextricably bound in some area codes while holding little correlation in others. Pew Research Center data on the 2020 electorate reveals that 79 percent of registered voters who identified as Republican fell under some Christian denomination; 32 percent of this demographic self-identified as white evangelical Protestants. On the other side of the political spectrum, 52 percent of Democrats were Christian, and the numbers were split relatively evenly among Christianity’s varied branches. Religion –– and specifically evangelical Protestantism –– has long held a central role in right-wing politics, but recently, it has mobilized.

To U.S. history teacher David Minhondo, extreme thought lies at the root of extreme action. America’s political climate and other recent developments have created the perfect storm for such radicalism to thrive.

“[First], there’s the hyperbolic culture of today’s American media, where everything is talked about in apocalyptic terms, like ‘the war on’ this or ‘the war on’ that; everything is built up to be an all-or-nothing situation,” Minhondo said. “I think that gets mirrored in some churches …. A lot of denominations of evangelicals believe in the rapture, and so they’re constantly talking about the end of the world coming and final judgment, and so I think that there’s kind of a combination of those things where your worldview is constantly on edge.”

When fear is prevalent, answers are sought out, and in a polarized, exaggerative atmosphere, the promise of comfort can lay with whoever has those answers, Minhondo explains. But both truth and some aspects of religion have become warped as the crowds claiming to have solutions have expanded, opening the floor for falsehoods.

“Religion has dominated the earth since the birth of civilization [because] people sought out answers. ‘Why does the sun rise?’ Somebody needed to explain this, so religion was the answer –– it was the way that people were able to cope with the seemingly chaotic and oftentimes random way that the universe seemed to play out,” Minhondo said. “And we like to think ourselves beyond that, right? We are becoming a more secular society, but we still seek order from chaos, and even if we’re not using religion to do that as much, it can give us answers, [as can other sources].”

The sheer breadth of these alternative sources can at times lend a hand to misinformation.

“That opens up a vacuum where people are going to seek answers from conspiracy theories, for example. Many people have shunned religion; they can’t believe their media; they don’t believe their politicians, so they get roped into QAnon and these crazy theories,” Minhondo said.

Conspiracies aside, religion and politics take on dramatically varied forms across the country, and their intersection in each region of the U.S. reveals something different about its inhabitants. In Marin, evangelical Protestantism has few footholds –– objectively, no religion does on a comparative level, according to Joey Martin, Hillside Church’s Director of Student Ministries. A Texas native, Martin grew up next to “megachurches” that drew in tens of thousands of attendees each weekend, making for quite different-looking Sundays than those he now experiences in Marin.

“I wouldn’t say Marin is a religious county at all, but I do believe there are people who definitely have a spiritual sense to them,” Martin said. “The largest church in Marin County would probably be one of the smallest churches in the town that I grew up in, which has a population the size of Novato. Here, it’s not normal to go to a church that has thousands of people there on the weekend.”

Faith still has its pulses across the county, but local links to places of worship are still relatively weak. Of all Marin residents, approximately 36 percent followed some Christian denomination in 2009, with 30 percent identifying as Roman Catholic, according to data from the University of Southern California’s Center for Religion and Civic Culture. In a January 2021 Bark survey, 58 percent of Redwood students claimed to not subscribe to a faith. Because more people are unaffiliated with any religion than are religious in Marin, secularism, like political liberalism, has a strong local presence. In fact, according to Minhondo, the two may be closely intertwined.

“In Marin, religion is not as overt: you’re not seen as weird for being Jewish or Muslim or Catholic or whatever …. In a place like Texas, where those concepts are more foreign –– where you don’t run into a Jewish person every day –– you’re more apt to believe in stereotypes because you’re not interacting with people like that on a day-to-day basis. And so you sort of end up with your worldview being influenced by your vote,” Minhondo said.

One religion does not dominate mainstream thought in Marin, facilitating a loose relationship between political and religious affiliation. However, this scarcity of faith may correlate to Marin’s left-leaning political outlook, the Pew data suggests. And while political and religious outlooks are somewhat unattached with one another here, a bond does exist. About 38 percent of religious Redwood students believe that their political convictions may be influenced by their faith, the January 2021 Bark survey revealed. Three percent of respondents reported that the two are certainly connected.

This connection is even more prevalent on a national scale. A 2016 survey released by Barna Group, a research firm specializing in faith and culture-related analysis, had 46 percent of respondents nationwide report religion as their primary source of political influence.

Northeastern Pennsylvania resident Sarah Block, who was raised evangelical Christian and now identifies as simply Christian –– a personal evolution she characterizes as “complicated” –– lives in a region that wholly counters Marin’s political and religious affiliations.

“Political and Christian conservatism are for sure interrelated [here]… I know of people who supported the [Capitol] riot and didn’t see it as problematic, [but] I also know people who see it as hugely problematic,” Block said.

The separation of church and state is an integral cornerstone of our federal system’s ideological basis, but it was never intended to apply at the citizenry level –– religion is deemed a healthy feature of civil society by a majority of Americans, says 2019 Pew data. However, Martin fears the intersection between the two has crossed lines in some cases, breaking essential theological standards and abetting generalizations.

“Christianity shouldn’t be used as a pedestal to promote someone other than Jesus, and sadly, that’s not the case [anymore]: you see these pastors that have influence in larger gatherings promoting and endorsing political figures, which can be very dangerous because they’re tying their religious belief to someone else other than who the Bible points us to, which is Jesus,” Martin said. “In the last election and the election before that, it became this assumption that ‘oh, if you’re a Christian, that means you’re voting for this person,’ which should not be the case at all.”

The January Capitol insurrection not only solidified these assumptions and the presence of evangelical Trumpism to many, but effectively smeared Catholicism’s name to some as well. In a Jan. 28 article from The Atlantic, Representative Adam Kinzinger, a Christian Congressman from Illinois, referenced the decline of his faith’s image in the public eye.

“[Looking at] the reputation of Christianity today versus five years ago, I feel very comfortable saying it’s a lot worse …. I think we have lost a lot of moral authority,” Kinzinger said in a commentary on recent events.

To Martin, the type of Christianity marching in D.C. in early January was almost unrecognizable.

“As I watched the Capitol storming and saw flags [reading] ‘Don’t Tread On Me’ waving next to [flags saying] ‘Jesus saves 2020,’ my first thought was, ‘what Jesus are they talking about?’” Martin said. “Because the Jesus we read [about] in the Bible is believed to be a true figure who promoted peace, who promoted love and promoted conviction as well, but done in a way that lifts up God and allows people to understand the better in themselves, which was very different from what was portrayed at the storming.”

Amending this will take time: putting faith in faith is a complicated task. To Martin, an initial step the church can take to make up ground is encouraging its proponents and followers to evaluate their grasp on what Christianity truly means.

“These people are very vocal about what they believe and why they believe it, and even though they want to say that to be pro-Trump is to be pro-Christian, it’s very false,” Martin said. “For us, the real church has to step up and reclaim, even though it might not fall on good ears, the real Jesus.”