COVID-19 in the Canal District

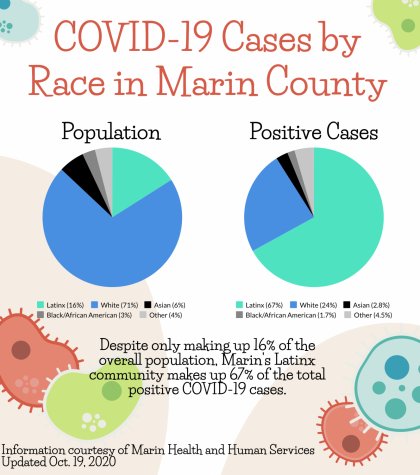

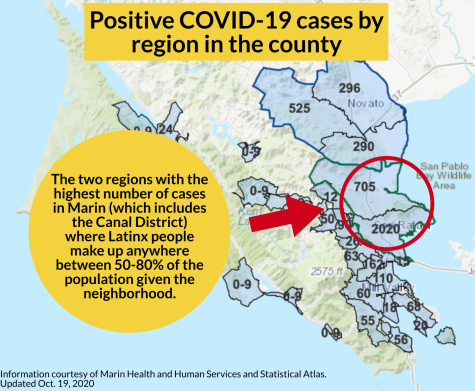

Marin County is the most racially disparate county in all of California, according to Race Counts, a Californian organization aiming to inform citizens about racial inequalities within the state. Racial disparity is the difference in the treatment of one race to the next — though it does not necessarily come from a place of intentional prejudice or racism. This racial divide has manifested itself most recently in Marin throughout the duration of the pandemic, particularly in the Canal District, where 93.9 percent of residents are of Latinx backgrounds, according to Statistical Analysis. Despite the fact that Marin’s Latinx population composes 16 percent of Marin’s population, it made up 67 percent of the total positive COVID-19 cases as of Oct. 19, 2020, according to data from Marin Health and Human Services.

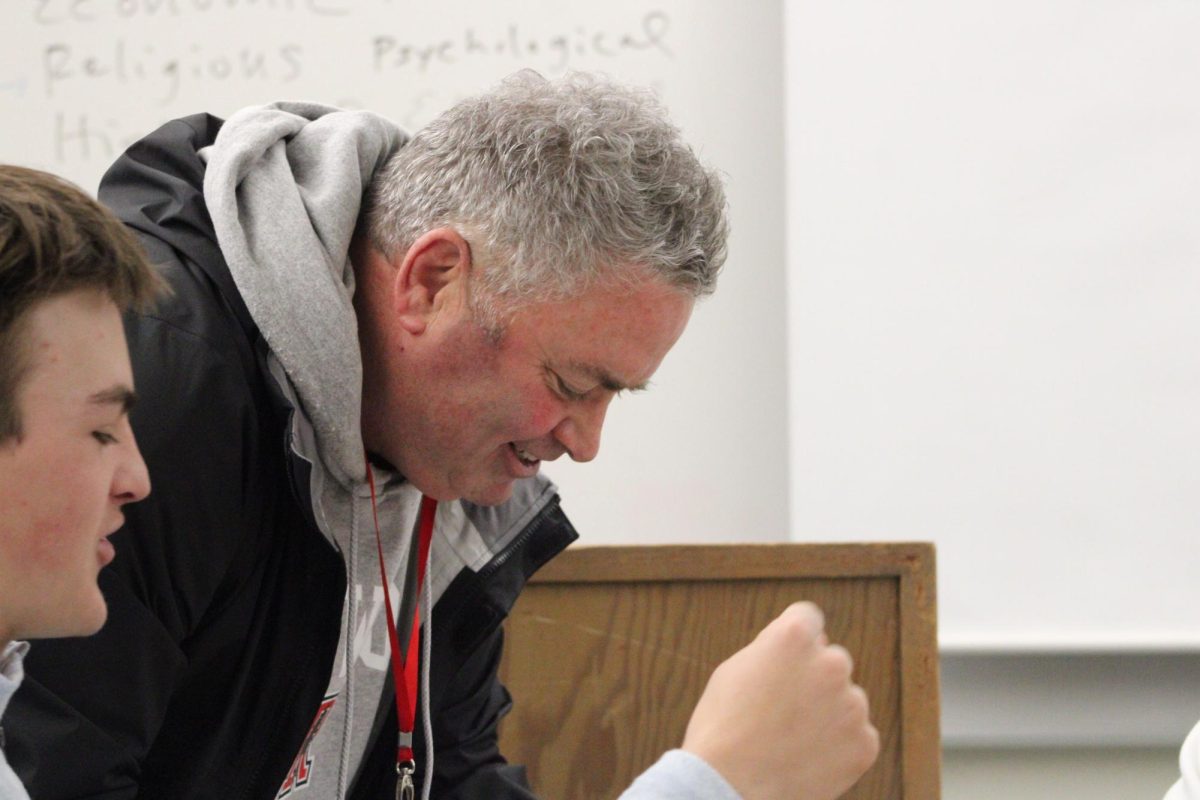

Dr. Gregg Tolliver, MD, MPH, Clinical Infectious Diseases Medical Director at Marin Health, is not surprised by the Latinx community’s high percentage of positive cases.

“The bottom line is that when you look at the density of people living in the population [in the Canal], it would be very difficult [for them] to isolate [themselves] if a family member tested positive. [People who live in the Canal] are 15 times more likely to be sharing a room with someone else compared to the average population,” Tolliver said.

According to the U.S. 2010 Census, the Canal District is the second most densely populated district in Marin, second only to San Quentin State Prison.

Maria Fernanda Civano, a Spanish teacher at Redwood, credits this dense population to Latinx cultural family values.

“You’re talking about Latinx communities that historically have multigenerational households. You have grandparents and uncles; you have a lot of people in one dwelling. They cannot isolate. They cannot put the kids to one side, parents to the other. They are all together,” Civano said.

The exceedingly high number of cases in the Latinx community could also be attributed to poverty in the Canal District. According to Healthy Marin, 18.9 percent of Marin’s Latinx population lives below the poverty line.

“[COVID-19] is a disease of poverty. [With] any respiratory, transferable, infectious disease, the wealthier you are, the easier it is for you to isolate yourself and buy masks. If you need to get the testing, if you need to get a computer to do your zoom classes or meetings, all of that is easier [when you are wealthy],” Tolliver said.

Not only are residents of the Canal District less likely to be able to afford basic safety necessities during the pandemic, but they are also more likely to work in lower paying jobs. The average Latinx household earns about half the annual income of a white household in Marin according to Race Counts, and therefore, they need to continue working throughout the pandemic in order to maintain some form of financial stability. This often puts them at a higher risk for contracting COVID-19.

“A lot of people in the Latinx community work the jobs that other people don’t want to do [during the pandemic]. Things like grocery store cashiers, gas station clerks, gardeners and house cleaners: [essential jobs] where they can work in person in order to earn a substantial wage during these difficult times,” Tolliver said.

Civano also believes that, in addition to financial motives in the Latinx community, there is also a cultural motive to keep working, even if they feel the symptoms of COVID-19.

“When [people in the Latinx community] feel some symptoms, they keep going, and they’re like, ‘Ah, it’s just a cold, whatever,’” Civano said. “There’s this part of them that wants to fight it and stay strong and continue working.”

Not only do economic and cultural factors affect higher case percentages in Latinx communities, but Tolliver also connects the disparity in positive cases to the amount of stress that the pandemic places on lower-income families.

“All that stress, things like, ‘Am I going to be able to feed my child? If I get sick am I going to lose my apartment because I can’t work?’ The fear of possible persecution or deportation adds to the economic insecurities for some of the Latinx population,” Tolliver said. “Then there’s the fear of the disease itself. All [of] that actually impacts your immune system; the stress can actually significantly impact how much people suffer from the disease.”

Distance Learning in the Canal District

Remote learning undoubtedly has slowed the pace of learning across the nation; but for some students, learning momentarily stopped. According to a report from the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee, as of 2017, 12 million students didn’t have broadband internet in their homes, which creates a serious obstacle for remote learning.

Even before remote learning was imposed by Marin’s schools, the education gap had persisted between students of varying socioeconomic statuses. The intersections between race and class keep American schools segregated, furthering the divide between high and low-income students. The majority of nonwhite school districts in the U.S. receive an average of $23 billion less than predominantly white school districts, despite serving roughly the same number of students, according to a 2019 study from EdBuild, a school funding research group.

These racial disparities also coincide on a local level. According to Marin Promise’s qualitative data, Latinx college readiness rates were only 35 percent, while rates for white and Asian students surpassed 70 percent in 2015 and 2016. This data comes as a result of the American public school system, which derives its funding from property tax and local income. Backed by robust community fundraising programs, public schools in wealthier areas can surpass those in poorer areas, driving a cycle of poverty.

Since March, most high school students have attended school in an online format. If a student does not have access to a computer or WiFi, they simply miss school. According to a recent Bark survey, 69 percent of Redwood students have access to stable WiFi for remote learning. Canal Alliance, a non-profit helping first-generation immigrants, surveyed Canal residents in March. By comparison, about 44 percent of Canal residents stated it was difficult to connect to the internet, indicating a majority of Redwood students were better equipped to learn at home compared to Canal students. Michael Gomez, the supervisor of Canal Alliance’s university prep, spoke on this technology divide between the Canal district and the rest of Marin.

“About one to two weeks ago, Canal Alliance collaborated with Marin County to put up a mass network, which is an open WiFi network in the Canal. Prior to that, if students needed WiFi, they needed to get hotspots from the school, which ran out pretty quickly,” Gomez said.

Nevertheless, San Rafael City Schools (SRCS) have made major progress in connecting all students to remote learning platforms. According to Sarah Ashton, the Chief Technology Officer for San Rafael City Schools, 65 to 70 percent of SRCS students currently have Chromebooks distributed by the district.

In the spring semester of 2020, Gomez saw firsthand the demotivating effects technology issues have had on the 49 high school students in the program. Class credit requirements were inconsistent amongst teachers because the pass or fail grading system sometimes accepted the bare minimum, which led to a further lack of engagement from some students. In other cases, grades were held to the same standard for every student, regardless of remote learning issues. In either situation, kids living in the Canal District were at a disadvantage.

“One teacher was pretty much like, ‘I know you missed these [assignments], but to earn a passing grade, you’re going to have to do 100 percent of everything that’s left in the semester.’ I find that frustrating because that’s a very large ask for students who face barriers in education,” Gomez said.

Even those with remote learning capabilities fell behind at home, especially when surrounded by family members who speak English as their second language. Gomez adds that students who are learning a second language rely heavily on engagement from a teacher.

Face-to-face connections are not only meaningful at school, but also at Canal Alliance. Previously the Canal Alliance building was open after school to provide snacks, tutoring services and college counseling. Without this supportive environment, Canal students struggle to find spaces to focus in their homes which usually house more than one immediate family. Brent Arndt, an English Language Development (ELD) teacher at San Rafael High School, says there have been discussions about the notion of opening classrooms on-site for a limited number of students to sit in during their Zoom classes, but a formal proposal has not been set forth yet.

Inevitably, the achievement gap will skyrocket if low-income students cannot attend Zooms or focus in class. Ashton believes the education system must focus on equity versus equality, which are often used interchangeably by mistake. Equality means providing the same resources to everyone, whereas equity means providing differing amounts of resources depending on the circumstances. Ashton highlights this significance in helping individuals meet their needs.

“I think technology is a tool that positions us in a place where we can ensure all students have access to an excellent education. We also need to look at our policies and practices that will address the more systemic inequalities and take the time to look at each student individually to see what each student needs,” Ashton said.

A more controversial method for preventing the widening of the achievement gap consists of returning to in-person classes. Arndt believes that a science-based, apolocial analysis, weighing the risks of opening schools and the mental health risks of staying home, points to opening up schools.

“I would say if there’s something that people in the community at large can do, it would be to advocate for prioritizing ELD students and Special Ed students, our most vulnerable populations, to be the first students who have the opportunity to start returning to in-person classes,” Arndt said.

Despite hardships, Gomez has witnessed kids in his program develop valuable skills and gain new perspectives.

“Coming from challenging circumstances or having to overcome barriers, I think students have a really unique perspective and a willingness to help people and help themselves,” Gomez said.

How to Help

The only way to ensure both the health and education of the Latinx community in Marin is to motivate change at a state level. Making efforts to minimize the financial gap between different races can provide for equal educational opportunities, as well as help families stay safe during a global pandemic. As a short term solution within Marin, donating and offering volunteer services to Canal Alliance will allow Latinx families to get the support they need during these troubling times.