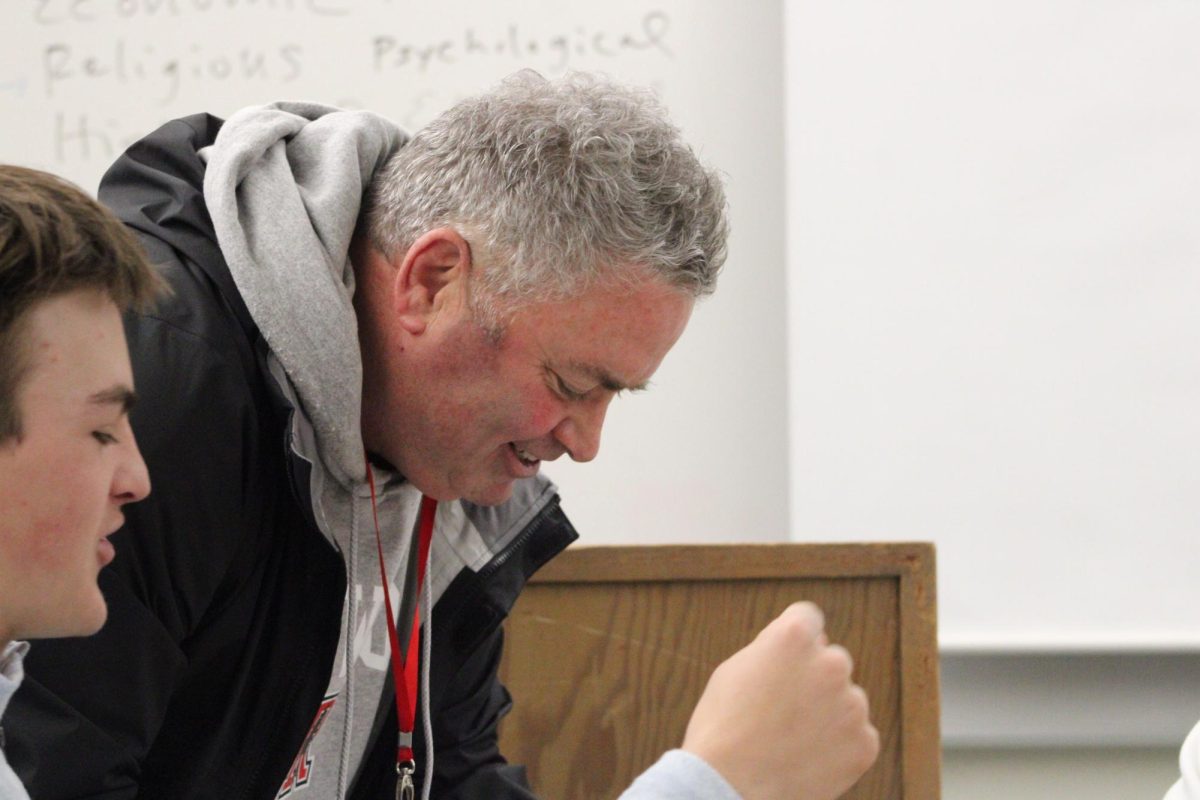

Mill Valley, Muir Beach, Fairfax and Corte Madera are just four hosts to thousands of local residents.

Though these cities have housed former Redwood student “Olivia” multiple times, they are not necessarily dear to her heart. Olivia, who has requested to remain anonymous, has moved 15 times within the boundaries of Marin throughout her 17 years of life. The lack of affordable housing in Marin has largely contributed to this constant resettling, but her case is not unique. In recent decades, local vacancy rates have plummeted while property values have skyrocketed, and what remains are limited housing options for those with low incomes.

Olivia finds her projected image at risk because of this county-wide trend.

“My biggest issue with [affordable housing] is the stigma around it; whenever some people realize they’re wealthier than you, they tend to be really judgmental and make a lot of assumptions about you,” Olivia said. “Just because I’ve lived in an apartment doesn’t mean I can’t afford food or anything––it’s just because we live in Marin. It’s like you either have to be wealthy or [it feels] like you can’t survive here.”

It appears some low-income residents have had similar experiences. According to the Guardian, an investigation by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in 2009 found that Marin’s shortage of affordable housing played a significant role in the historical concentration of Latino and African American residents in specific neighborhoods. Marin City stands as a notable case of this.

Constructed during World War II to house Sausalito shipyard workers, Marin City began as a humble government-financed complex that accommodated a variety of domestic migrants seeking well-paid labor. As the United States’ war effort waned following American victories abroad, many white laborers left the complex. Meanwhile, many African Americans and individuals of other races found themselves lingering because segregation prevented much social and physical mobility at the time.

Today, Marin City still stands a diverse community, but its residences remain the stark reflection of disregarded needs and inadequate federal funding. Golden Gate Village, Marin City’s government-owned complex built in 1960, now houses some 300 families and could require “$16 million in immediate improvements to bring up to minimum HUD standards,” as stated in the Marin Independent Journal (Marin IJ). The units within the Village are not only home to numerous demographics but to countless health and safety deficiencies, including missing doors, inoperable appliances, vermin and mold, a 2018 inspection report showed.

Following HUD’s 2009 probe, county officials agreed to permit the federal agency to oversee its housing progressions. Though significant progress has not been made since, local organizations and city councils have been working to address affordable housing discrepancies case-by-case.

On Tuesday, Feb. 11, county supervisors approved a report to be submitted to HUD for authorization. The analysis described existing impediments to fair housing in Marin and included several recommendations to combat the county’s obstacles that often impede on homeownership opportunities for low-income people of color. Proposals included creating a community land trust to confront skyrocketing prices for development and rezoning existing sites to construct more dense units.

A Marin IJ article on the report included the perspectives of several community advisors, including that of advisory committee member Ron Brown, who voiced clear-cut solutions to the complex issue.

“It is impossible to reach any goal for equity and reduce the barriers to fair housing choice without constructing more units, particularly in the price range affordable to low and very low-income residents,” Brown said in a committee meeting.

The idea of equal housing opportunities is often agreed upon by some county residents in theory; in the presidential primaries of early March, locals voted overwhelmingly for Democrats. Party front runners like Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders often advocate for equitable housing opportunities to combat discrimination on a large scale. In practice, however, constructing more housing units is often delayed or dismissed by leading community members.

December of 2017 saw a recent example of this postponement: a 400-unit project proposal on a former Baptist seminary in Strawberry, the third proposal for the area in six years, was rejected by county supervisors. Another project that set out to build 224 low-income senior and family homes on a different site was also stalled in recent years, according to the Los Angeles Times. A separate proposal to redevelop a worn-down strip mall on five acres near Lucas Valley into 82 apartments for low-income residents lost its fuel as well.

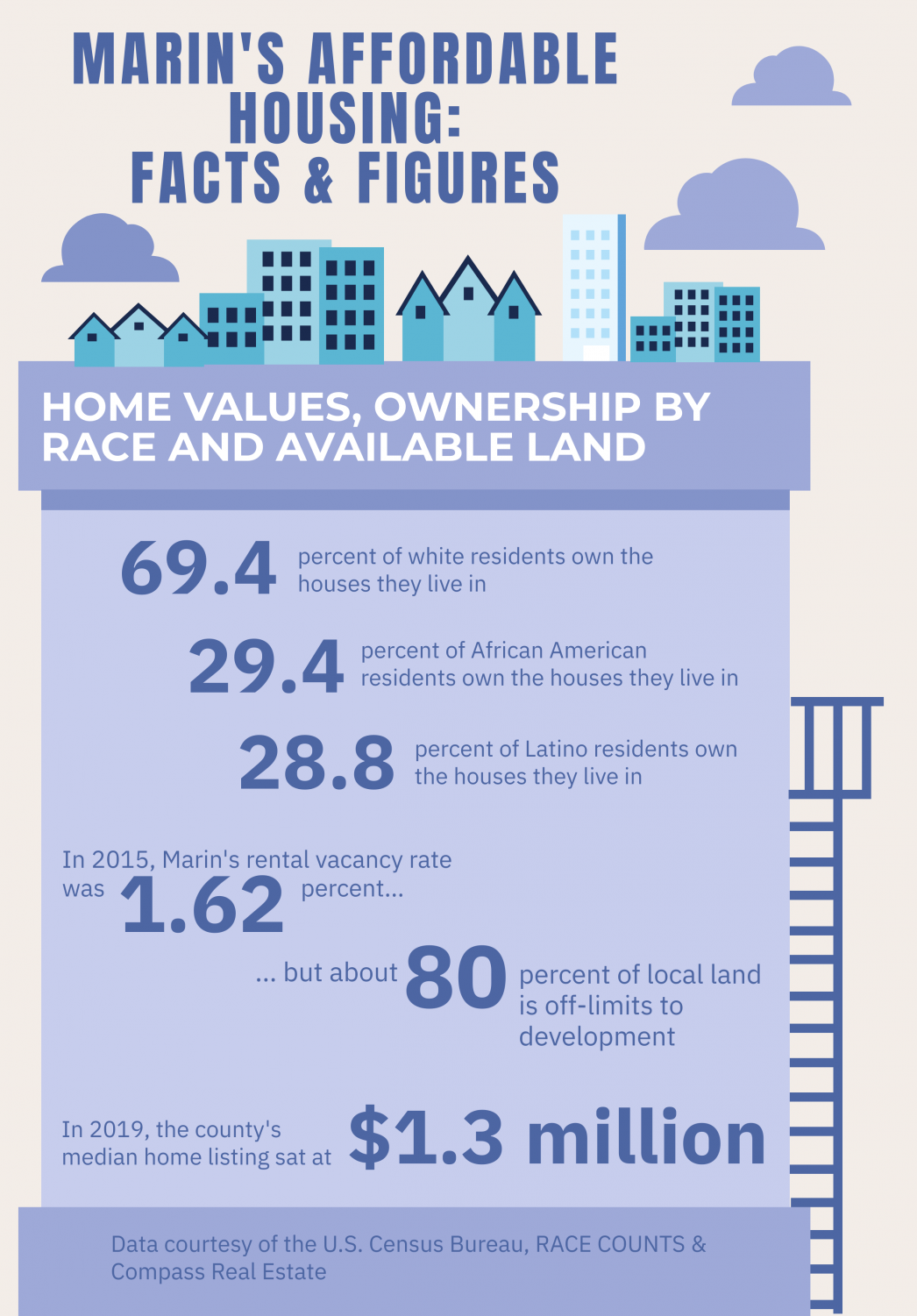

This inaction in creating abundant housing at affordable prices harms opportunities for upward mobility amongst several groups. RACE COUNTS, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit providing data on racial discrepancies in California, ranks Marin as “the most racially disparate county in [the state].” Inequities are especially apparent in terms of homeownership by race, as an approximated 69.4 percent of white residents reside in owner-occupied housing units in Marin, contrasted to a 29.4 percent rate among African American residents and a 28.8 percent rate among Latinos, groups that collectively hold the lowest numbers.

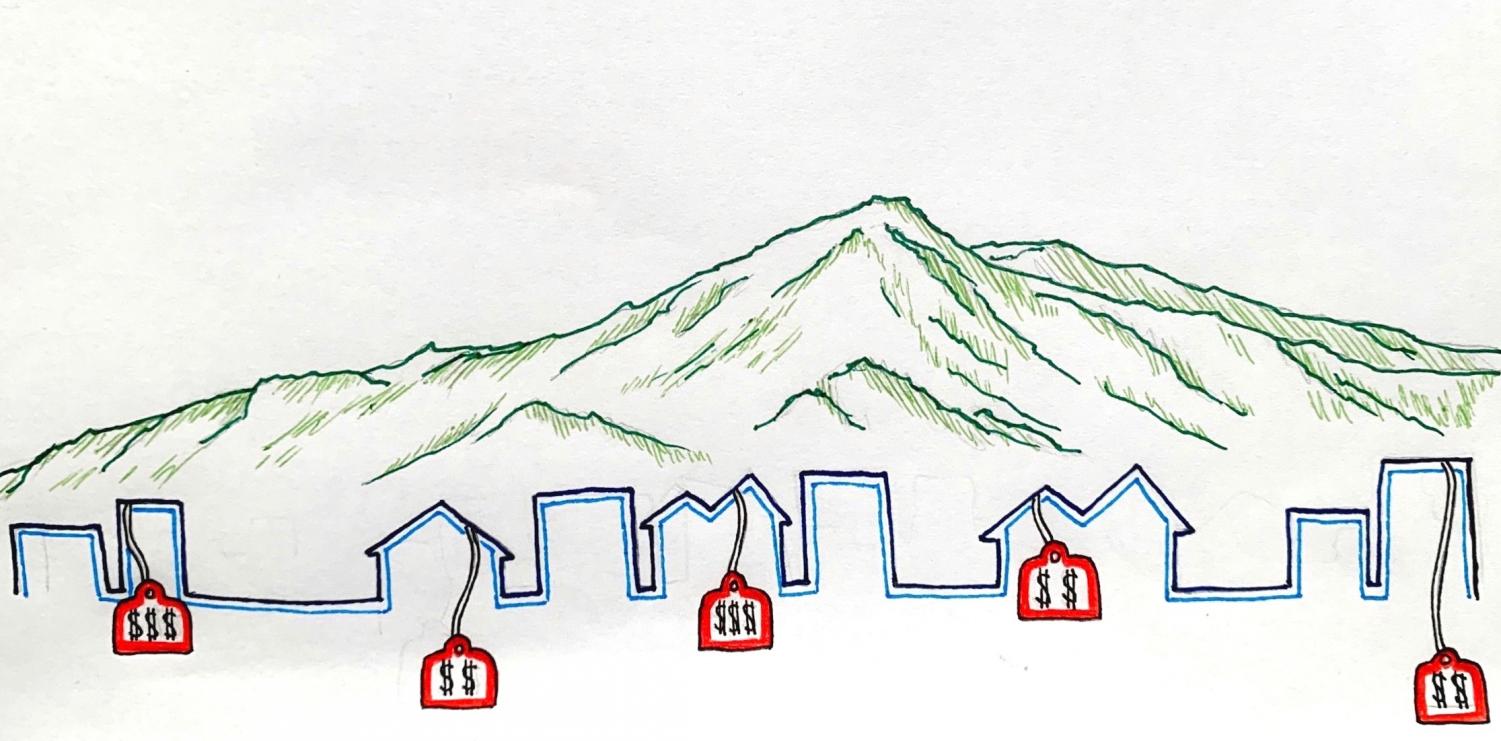

Soaring prices for permanent housing within Marin often prevent homeownership for many income groups. Compass Real Estate reports that 2019’s county median home listing sat at $1.3 million. The value recently peaked in 2018, hitting almost $1.4 million at a height in price appreciation. Compass’ January report claimed one negative byproduct of this unprecedented pricing is the increasing outwards migration of businesses and homeowners, yet the Bay Area still steadily attracts workers and families of countless demographics. Population growth plays a factor in housing availability, but affordability and land capacities are central to the crisis.

Olivia has seen these boundaries affect her family first-hand, and believes that the county’s median income also plays a role in defining who can independently afford housing and who cannot. According to 2019 Census estimates, Marin County’s median household income stood at $110,217, which towers over the national median of $63,179. For those living below this high line, affording life in some parts of Marin can feel ostracizing.

“The smallest apartment I ever lived in was a one-bedroom and it was almost $2,000 [per month], which is really expensive. A lot of lower income families here in Marin would be middle class and even upper-middle class in other counties. When people say Marin’s a bubble, it really is financially; people just don’t really see how different it is in other places,” Olivia said. “If [my family and I] lived anywhere else, we would live in such a big, great place. But since Marin [seems to] have been set up for wealthy families, it’s just not like that here.”

The lack of reasonably-priced units is not unique to Marin. The research division of McKinsey & Company, a management consulting firm, finds that “the combination of higher demand for housing and insufficient supply has inevitably pushed up California’s real estate prices…nearly half of California’s households cannot afford the cost of housing in their local market [nowadays].” Of the approximated 5.9 million low-income households unable to afford the costs in their distinct regions, about 3.7 million, or 62 percent, reside in the inner Bay Area and greater Los Angeles county.

In a detailed report from 2016, the organization claimed California would have to build 3.5 million housing units by 2025 to close the state’s existing affordable housing gap, which they estimate to sit between $50 million to $60 million annually. $10.4 billion of this gap is concentrated in the Bay Area’s markets. Though a statewide crisis, Marin’s lack of affordable housing is especially pressing.

Because increasing real estate prices are unreachable for several demographics, the need for low-income housing remains prevalent, yet the drive to build units remains relatively low given high costs for development, a Marin IJ article stated. Groups such as the Marin Housing Authority (MHA) work to combat discrepancies in this availability.

Deputy director Kimberly Carroll manages MHA’s programs, including their Section Eight Housing Choice Voucher program, which comes in the form of government subsidies to assist those with low incomes secure housing in the county. Regardless of the aid MHA provides, limits on physical space often pose great challenges for the entity and prospective residents alike. Carroll portrays the matter as a supply and demand issue, given about 80 percent of Marin is open space that is off-limits to development.

“We’re essentially saturated; we’ve got around a less than one percent vacancy rate for people. So even if you have a lot of money and want to live here, it’s hard to find a place to rent because there’s so few,” Carroll said. “If you need an affordable place, you can’t really get anything without a voucher. So then that creates a community that’s mostly wealthy people and those who want to work at our Starbucks or as our school teachers and things can’t live here.”

MHA works around the formidable obstacle of usable land limits, but Carroll sees that community attitudes surrounding affordable units can curb development efforts as well. Though Carroll and other employees take creative approaches like repurposing existing buildings for affordable units, these negative views are difficult to navigate around.

“We don’t have any space to build [in] right now, and we’ve got to figure out ways to make it easier for developers to create affordable housing…. However, some [have the attitude] of ‘not in my backyard;’ they don’t even want a unit built that’s going to be high-end, and they certainly don’t want something built that might be affordable,” Carroll said. “I think people think they have this idea of what a low income person is and what that does is create a divide.”

Local food industry professional Ari Maslow observes similar attitudes in the context of service occupations. According to Maslow, although 80 percent of his restaurant employees live within Marin’s boundaries, most reside in more affordable areas such as San Rafael, which may affect their psyche as they serve those living in more wealthy zip codes.

“There’s probably a feeling that they’re kind of on the borderline of the community. That they feel a part of it, but that there’s certain natural barriers that prevent them from being a ‘part’ of it. I would say there is a feeling of separation,” Maslow said. “Even with the ones who do live in Marin, I feel that there’s different levels of workforce, and this workforce is definitely kind of in its own community.”

Maslow sees that increases in the density and availability of local affordable housing would not only benefit those needing it, but would assist local employers such as himself that seek an accessible workforce.

“It would increase the employer’s ability to hire at better wages with more skilled labor. The more [service workers that live locally,] the more of a pool that you have to choose from. As a professional, you want to choose what’s going to best suit your industry, and having more options [is desirable.] Then businesses grow and they’re stronger…It’s kind of this compounding effect. It’s just better for everyone when a business runs well,” Maslow said.

To foster an inclusive county that is home to various classes and workers will take time and extensive planning, policy change and dedication. Recent efforts show some promise: the Strawberry Baptist site’s rejected plan found new life in February when the property’s owner debuted a new plan that would construct more units than initially proposed. According to the Marin IJ, 50 of the 337 new residences would be affordable. Other recent MHA victories, such as secured approval for a 53-unit senior property in Fairfax, are a step in the right direction as well.

Developments will take time, however, and community sentiments may take even longer to dissolve. For now, many, including Olivia, hope for the best.

“If there was more opportunity for affordable housing in Marin, that would [further integrate] financial and racial diversity, and that would [help the county] in so many different [ways],” Olivia said.