Edmond Richardson is a 34-year-old father, filmmaker and computer programmer whose 2020 goal is to prioritize his happiness. He works to combat “oppression, separation and the dehumanization of all people” by helping produce videos that illuminate the injustices of the criminal justice system. His goal of happiness, however, sometimes feels unattainable, as he is surrounded by barbed wire and guards with over a decade until hope of parole. After meeting him at San Quentin State Prison on a field trip in February, we discovered the reason, or lack thereof, for his long sentence.

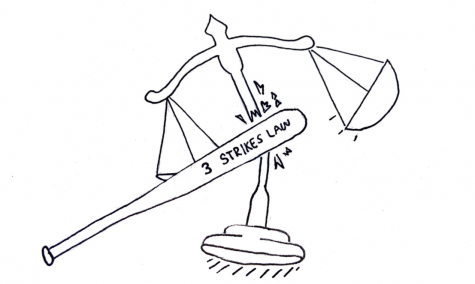

Growing up, Richardson struggled as one of eight children being raised by a single parent. He also encountered racial discrimination and continuously grappled with self-acceptance. After committing his third felony in 2010, an armed robbery in which he stole a book bag, he was sentenced to 25 years to life in prison under California’s 1994 Three Strikes Law. So far, he has served eight years of his sentence behind the bars of San Quentin State Prison. Richardson has dedicated his time in San Quentin to the prison’s acclaimed video channel, FirstWatch, and years of self-help rehabilitation through prisoner programs.

The restorative justice and educational aspects of San Quentin are nationally renowned, to the point where many incarcerated people told us they fought to be sent there. However, California’s Three Strikes Law directly counteracts San Quentin’s reformative efforts. It automatically sentences someone who has committed their third felony to life in prison regardless of the crime they committed, with 25 years until they can apply for parole. The rigidity of the law limits the flexibility of the trial as well as the judge’s ability to make varying decisions based on the gravity of the case.

According to the original proposal for the law, its purpose was to “keep murderers, rapists, and child molesters behind bars, where they belong” and stop repeat offenders. Albeit, the law was enacted for all serious felonies, which can range from murder and rape to burglary and drug trafficking, but it puts all third-time offenders in the same category and locks them behind bars for a significant amount of time. Though the law’s supporters claim it deters violent crime and stops repeat offenses, the homogenous nature of this law needs to be reformed.

Former U.S. President Bill Clinton regrets signing the bill. According to BBC, he admitted his “three strikes” crime bill introduced in the 1990s contributed to the problem of overpopulated prisons. Speaking to a civil rights group, Clinton said, “I signed a bill that made the problem worse, and I want to admit it. It put 100,000 more police officers on the streets but locked up minor actors for way too long.”

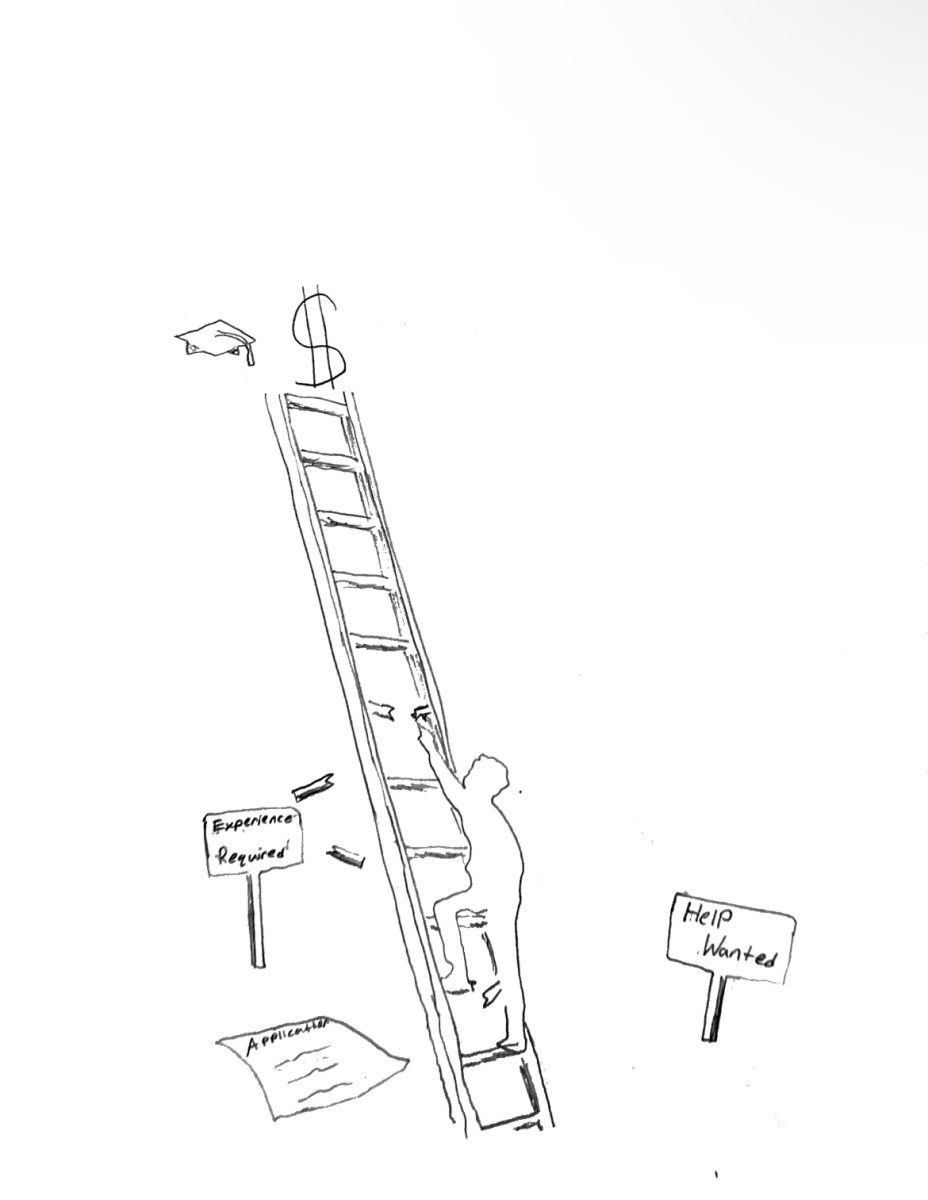

With the largest prison population in the world, it appears as though the U.S. wants to keep people in prison for as long as possible with laws like Three Strikes. In California, over 30 percent of incarcerated people are sentenced to life. It’s not only unjust to put varying crimes under the same standards, but a massive waste of money. According to the Legislative Analyst’s Office, it costs an average of $81,000 per year to incarcerate one inmate in California. These costs multiply under the Three Strikes Law as sentences lengthen considerably. The inmates incarcerated under the Three Strikes Law cost $1.3 billion in 2012, and the California auditor predicts that the law will cost up to $19 billion each year in the future.

In addition to its costs, statistics from the California Department of Corrections show that the law disproportionately affects minority populations. Over 45 percent of inmates serving life sentences under the Three Strikes Law are African American. The Three Strikes Law just adds to the prison population without addressing racial discrimination or community disadvantages.

Since its implementation, the Three Strikes Law has had a major effect on the make-up of the prison population. According to The Sentencing Project, despite the steady decrease in violent crime, life sentencing rates are still on the rise. California leads the nation with the highest number of life-sentenced inmates, according to PBS. The Three Strikes Law, despite its opportunities for parole, promotes life sentencing of prisoners without any support for rehabilitation.

With prison spending at ten percent of the state budget and education at only six percent, a better use of government funding would be to build restorative programs to prevent incarceration in the first place.

To amend the Three Strikes Law, nonprofit organization Unite The People has proposed a law called The People’s Fair Sentencing and Public Safety Act, which would impose a life sentence with the possibility of parole. It also takes into account whether a previous offense included rape, child molestation or murder. The measure needs to gain 623,000 in-person signatures from registered California voters before June 2020 to secure its place on the Nov. 2020 ballot.

Richardson has high potential and specialized skills that are being compromised by the boundaries of prison. With Three Strikes Law, he is out, benched for 25-plus years until he can petition to bat again.

To amend the Three Strikes Law, go to unitethepeople.org to help get the measure on the Nov. 2020 ballot.