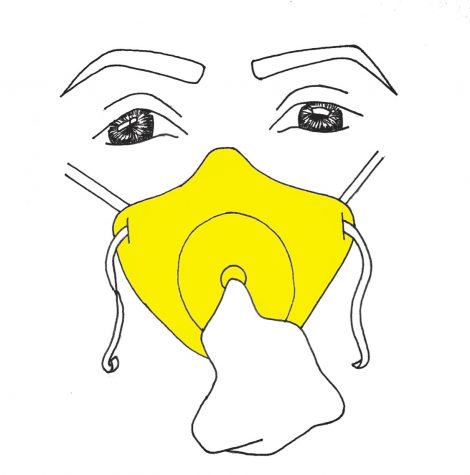

“You’ve probably flown on an airplane before. One of the things flight attendants [do] when they’re walking down the aisle doing their checks… is they’ll look at you (say you’re a parent) and tell you to… put your own mask on before you can assist your children,” Redwood parent Lisa Ames said. “And parents have the opposite inclination, right? Their inclination would be, oh, I have to help my kids first. But the problem with that is if something goes wrong, you pass out [from] lack of oxygen [and] all three of you are dead.”

Sometimes shifting priorities to focus on oneself can make all the difference. For Ames, who employs the metaphor for mental health purposes, this is certainly the case. Though her daily routine does not entail oxygen masks, the mother of two often discerns stress in her children, but regularly reminds herself of her own wellbeing’s worth as well. While juggling her numerous responsibilities, she keeps the airplane analogy close to heart—slowing down to address her personal needs proves an essential step before attending to other tasks. The value of self care applies to all generations, yet appears especially crucial in teenage demographics: 6.3 million Americans aged three to 17 have diagnosed anxiety or depression, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Flooded with various challenges unique to contemporary affairs, today’s youth can face both traditional and unprecedented strains, ranging from threats of gun violence to news of an ever-warming climate. As stressors permeate from several angles at developmentally vulnerable times, pressured adolescents can feel overworked, overwhelmed and may prematurely “burn out,” or experience decreased performance due to prolonged exhaustion. According to Penn Medicine, tuning into one’s needs and developing emotional maturity can offer a healthier alternative.

Although much of today’s youth may report strains more willingly due to reduced stigma around mental health, studies point to historic spikes in stress among adolescents. A 2018 survey by the American Psychological Association (APA) found that Generation Z, the cohort of individuals aged 15 to 21, was the least likely to report having “excellent or very good” mental health of all generations polled. 91 percent of survey participants between 18 and 21 years old admitted experiencing symptoms of stress within the month it was conducted compared to a 74 percent overall rate of all other age demographics.

Advancements still stand among these discouraging statistics. Of all Generation Z survey participants, 37 percent reported having received professional help for mental health complications, a number that topped all older respondents’ results.

To many, these progressions hold promise; to others, they aren’t enough. Local social worker and therapist Brenda Fishleder has worked in the counseling field for over three decades and has seen dramatic increases in stress, diagnosable anxiety and depression in Marin’s youth stemming from a wide range of issues. She attributes increases in local distress mostly greatly greatly to college aims, social media, drugs, peer pressures and desires to achieve.

Future aspirations and personal success often top local students’ list of priorities. A 2018 Pew Research Center poll found that 88 percent of participating teenagers felt an obligation to earn good grades, making academics a prominent stressor amongst adolescents nationally. This trend continues locally: given Marin’s status as home to many accomplished professionals, such a high-achieving environment can bring about pressure-loaded expectations for those trying to pave similar paths to success.

Redwood’s 97 percent graduation rate and 41 percent AP enrollment rate makes for a particularly competitive setting, especially compared to California’s 2018 graduation average of 83 percent. To get a leg up, many students attempt to set themselves apart in hopes of being admitted to prestigious colleges, according to Fishleder. The therapist has been an eyewitness to this increase in vying for distinction, and sees the trend as concerning.

“There’s so much pressure to do it all and to be unique in some way, but everybody stands out just by being themselves. [Nowadays] it’s like you have to create this image or this sort of schema of yourself that’s going to impress people. [Students take] more AP and honors classes, [and are engaged in] more work after school,” Fishleder said. “[This] cuts away into whatever time kids used to have for self care, for connections with family and friends or for even getting to know themselves and to develop an identity in a natural way.”

Despite this, stress, in the context of education and extracurriculars, is not necessarily harmful all of the time. Introduced irregularly or in small doses, “eustress,” a beneficial type of strain, can increase motivation, support the growth of certain skill sets and bring about a sense of accomplishment, according to TIME Magazine. However, when “distress,” the negative counterpart of eustress, is present regularly or too often, a more harmful narrative can follow.

Despite this, stress, in the context of education and extracurriculars, is not necessarily harmful all of the time. Introduced irregularly or in small doses, “eustress,” a beneficial type of strain, can increase motivation, support the growth of certain skill sets and bring about a sense of accomplishment, according to TIME Magazine. However, when “distress,” the negative counterpart of eustress, is present regularly or too often, a more harmful narrative can follow.

At the point where these everyday stressors persist or cause minor panic episodes over extended periods, chronic stress can come into the picture. APA characterizes the condition as “constant,” which in effect can be “psychologically and physically debilitating.” Left unmanaged, chronic stress can pose long-term threats to adolescents and adults alike.

Psychological strains can manifest themselves physically, and many teenagers may miss telltale signs of being overwhelmed. Physical symptoms such as headaches, muscle pains or spasms and faintness can provide insight on distress levels.

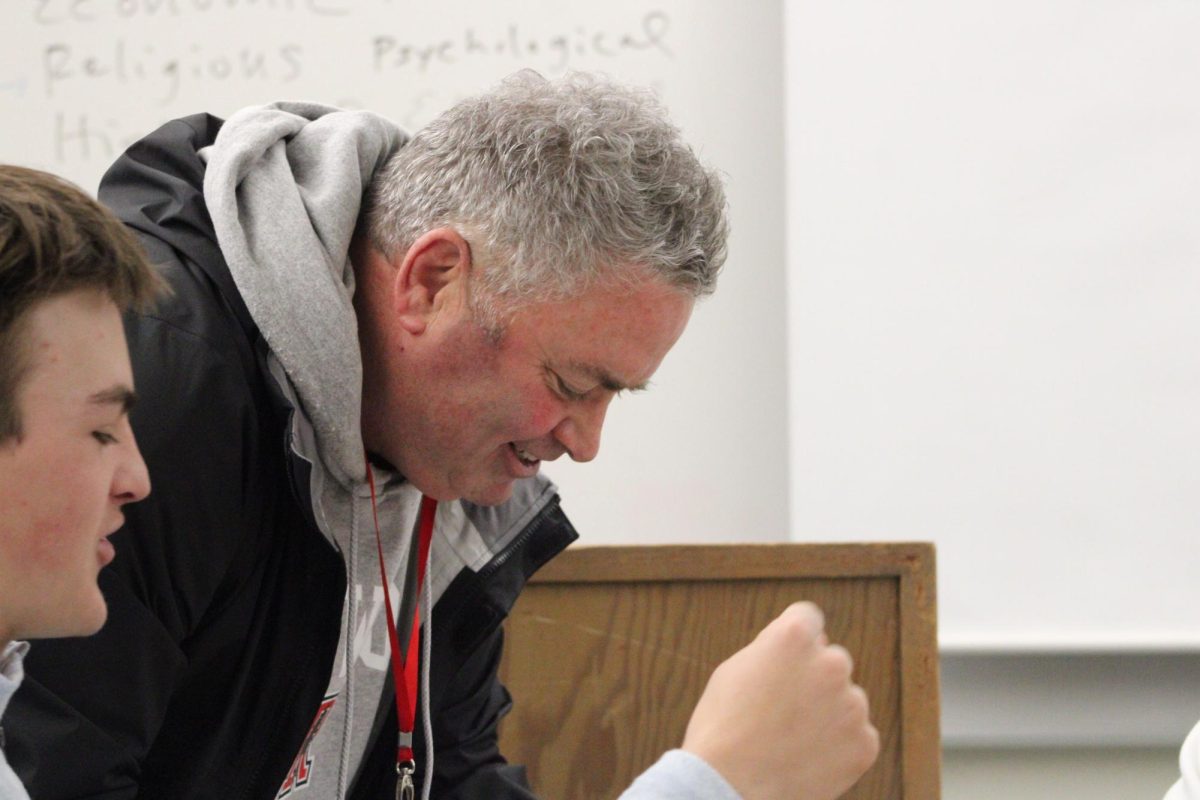

Redwood’s Wellness Center attempts to combat looming stressors by providing students with resources and counseling to manage mental and physical tensions. Wellness coordinator Jen Kenny-Baum sees numerous distress cases daily, and takes note of what students’ bodies may be communicating to them.

“I feel like [physical effects of stress] are one of the reasons a wellness center like this exists. Sometimes people are more comfortable with acknowledging what’s happening in their body rather than what’s going on mentally,” Kenny-Baum said. “Some talk about ‘health below the neck’ rather than ‘above the neck,’ and that’s how we pretend to separate the physical from the emotional, but they completely interact and affect each other.”

Over time, these relatively minor headaches or stomach pains can translate to much more alarming conditions if stress persists. According to APA, physical effects or indications can range from “anxiety, insomnia…and a weakened immune system” to major ailments like “heart disease, depression and obesity.”

Fishleder is well aware of the long-term consequences of chronic stress, and fears younger generations will suffer these fates if stress is not reasonably lowered or dealt with.

“If you have chronic stress, your heart is working harder, right? So it’s going to enlarge. The larger your heart, the more risky. Down the line [one can be] likely to get a heart attack or to get blood vessels filled with plaque. So that’s why I’m really passionate about it—I think [the way the world works] is setting [today’s youth] up for health issues,” Fishleder said.

Though local and national conditions are difficult to change, stressed individuals can make relatively simple adjustments at the personal level to better manage what is thrown at them. Many teenagers carry their coping mechanisms into adulthood, so early development of these strategies is vital, according to Fishleder.

“I love working with adolescents because it’s this great window of opportunity: you’re growing and you aren’t yet defined. This is the time to strengthen your [stress-coping habits]… It’s more important than math [and] English. It’s absolutely essential to have in order for your learning to really be exciting and promote stimulation, growth and success later in life,” Fishleder said.

Fishleder recognizes the positive developments districts have already made, but hopes local schools will place a greater emphasis on emotional regulation and coping education to give students head starts down healthy paths. Though many patients initially resist it, she personally recommends meditation, which she defines loosely to fit the needs of a range of adolescents.

“[Meditation] is any activity that you do that really takes your mind off stress and puts your body in a deeply relaxed state,” Fishleder said. For some people it’s playing music [or] drawing. For [others] it’s literally learning the skills of ‘emptying yourself.’ I don’t care what you do, but… commit to quieting your brain and nervous system.”

Kenny-Baum advises prioritizing nutrition, decent sleep and exercise even when time does not seem to allow for it. She also believes students must narrow their ambitions at times, for taking things day-by-day can make all the difference.

“I [have observed] a really common line of thought with people here,” Kenny-Baum said. “I see students [who will] take one test in the ninth grade and tie it to the outcome of [their] entire futures. They begin to only see one path…but it’s really about being in the moment.”

The toll stress can take on both the emotional and physical wellbeing of an adolescent today can impact their performance in the present and reverberate into their future, but Fishleder sees that if mental health literacy and self care is better taught, conditions may change. The therapist emphasizes change on a considerable scale to better prepare younger generations for higher education, the working world and beyond.

“We can’t really stop the road from changing… but the truth is, there’s a lot [we] can do to help [ourselves],” Fishleder said. “[Teenagers] are inheriting a lot now—that’s why I think change is so key because we want [them] to be healthier, stronger, more mindful and more capable of running this country… [they] are the ones that are next up. This is going to be in [their] hands. Let’s take better care of [them].”