A 14-year-old cannot legally obtain a driver’s license or watch an R-rated movie. They cannot vote in an election or purchase alcohol. They cannot buy lottery tickets, join the military or own property. But in the United States, they can be tried as an adult and spend their life behind bars.

Currently, only 1,200 minors are housed in juvenile facilities, while 10,000 minors are in adult facilities. According to The Economist, the number of adolescents registered in adult prisons increased by approximately 230 percent between 1990 and 2010.

The core of this issue lies in the fact that, while adolescents’ and adults’ decisions are sometimes judged within the same justice system, adolescent brains have not developed to the extent of adult brains. According to the National Center for Biotechnology Information, the brain continues to mature well into one’s twenties. The prefrontal cortex, the decision-making section of the brain, does not finish developing until about the age of 25. The reasonable solution for different stages of brain development should be different consequences for criminal activity. However, the current system allows for the same punishments to be given to both parties. Neuroscientific discoveries played a major role in the decision to eliminate the death penalty for minors in 2005, yet the system failed to make the same decision in regards to incarceration. Minors who make poor decisions are often not able to fully consider the consequences for their actions, thus the developmental state of the adolescent’s brain should be taken into deeper consideration when determining proper discipline.

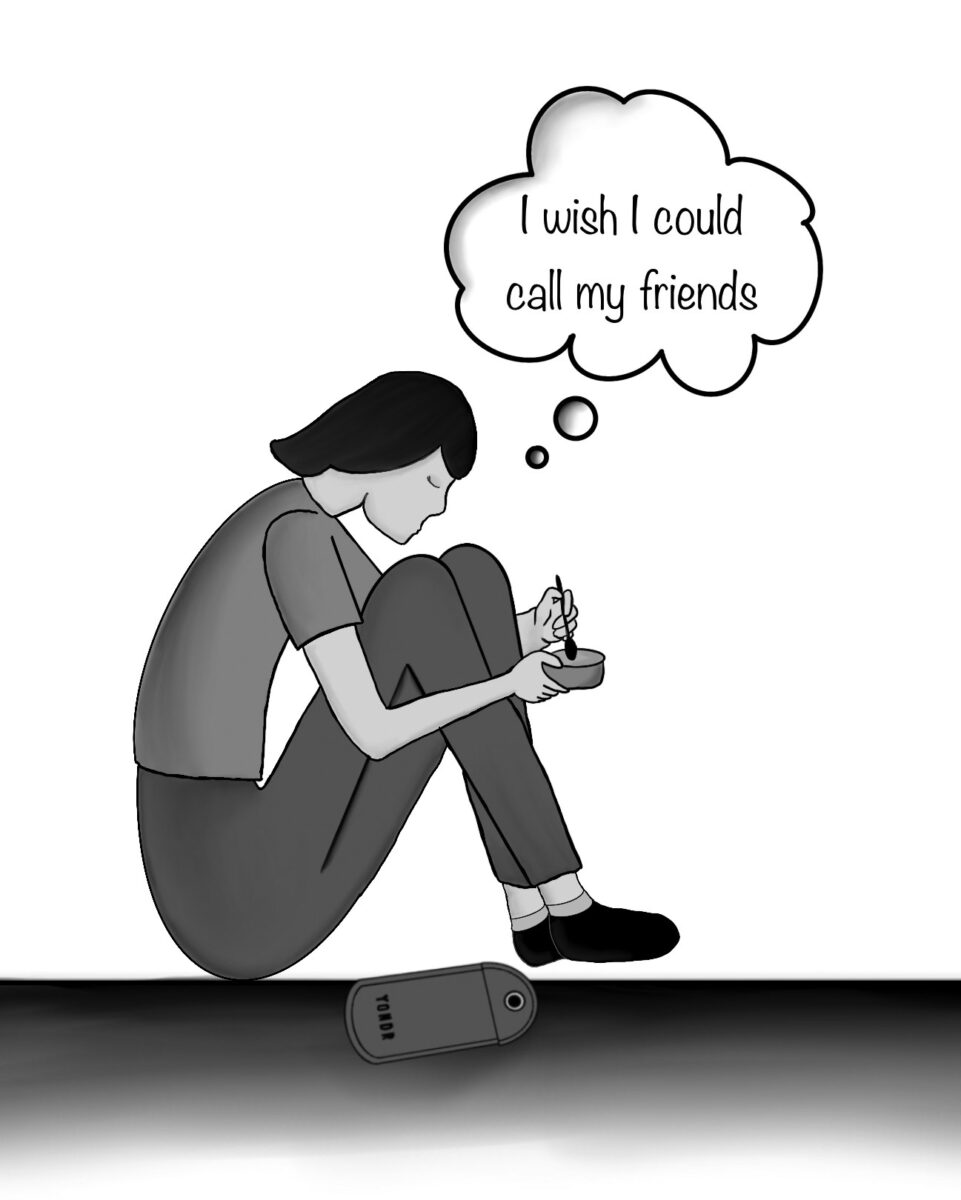

According to the Equal Justice Initiative, adolescents sent to adult facilities instead of juvenile facilities are five times more likely to be sexually assaulted and 36 times more likely to commit suicide in the years following imprisonment. Minors continue to be subjected to an environment that endangers their physical and mental well-being, despite the majority of them not endangering their potential inmates.

Besides damaging their physical and mental health, minors incarcerated in adult prisons face another issue: adolescents sent to these facilities are forever tarnished with a permanent mark on their record. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, the rate of unemployment among formerly incarcerated people is 27 percent. By comparison, the unemployment rate of the general population in the U.S. is 3.8 percent, according to Trading Economics. Additionally, children put into the adult criminal justice system are 34 percent more likely to be re-arrested as compared to those in the juvenile system.

It is cheaper to send youths to state facilities rather than to develop services to help rehabilitate these teenagers, according to the Justice Policy, a national nonprofit organization working to promote justice. Judges are often faced with no alternative other than to send minors to adult facilities because of the lack of financial means to pay for other options. By doing so they are placing money at a higher importance than the psyche of criminal adolescents. They are allowed to make these calls because Proposition 57, passed in 2016, gave judges the option to choose whether or not dependents as young as 14 should be tried in adult court.

Although it may seem like a solution to this financial dismay is unlikely, some states and counties have been able to fix this problem by implementing programs that replace proctor court cases. Adolescents in this system are usually sentenced with a type of community service instead of a permanent mark on their record. In Marin County, a rehabilitation program called Restorative Justice has been established. Jake Blum, a Redwood junior, has been working with Restorative Justice for close to three years.

“The goal is really just to help kids learn from their mistakes and give back to their community rather than being punished,” Blum said. “It’s about re-integrating these kids into the community.”

The main purpose of the criminal justice system is to remove dangerous felons from society. In contrast, the goal of the juvenile section of the justice system is to advise children to make better decisions in their future, offering rehabilitation and a chance at success. When the two systems overlap, the goals of each become conflated and are no longer effective. A 14-year-old is not seen as an adult in the eyes of our society, and for that reason it is clearly unjust that the justice system views them as one.