Crowds, food in the trash and wasted money. This describes the typical setting of the CEA at lunch. Students wait in food lines for what seems like hours, but shortly afterward most of the food ends up in garbage cans or are strewn across tables and the amphitheater, attracting seagulls and other pests. There are endless complaints about how the food tastes like cardboard, how it is too expensive and how Redwood needs to change its meal system. Many students realize that it is not worth it to eat at Redwood, and instead go off campus for higher quality food, or, like me, they bring their own lunches from home, which costs about one-third of the price of lunch from the CEA. If the prices were more reasonable and if the food tasted better, then I would buy lunch from the cafeteria. Although the food does not taste great and is too expensive, a recent move by the Trump Administration may have laid the foundation to solve this issue.

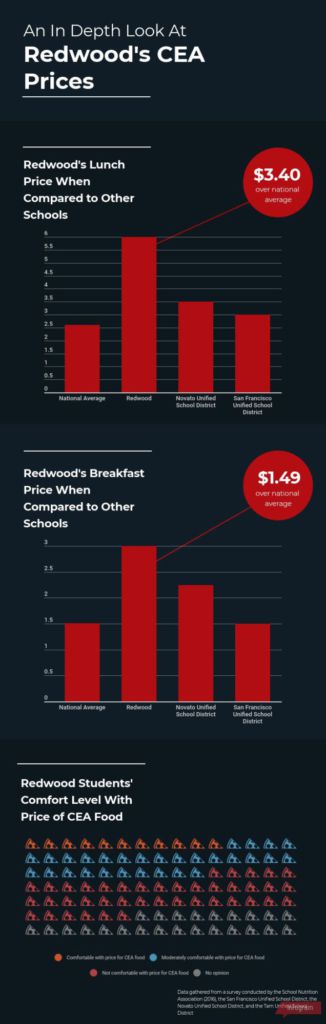

Redwood’s prices for food are more than double the nation’s average. In 2016, the average United States high school provided lunch for $2.60 and breakfast for $1.51, according to a survey conducted by the School Nutrition Association. In contrast, Redwood’s lunch costs $6 and its breakfast costs $3. This is outrageous. Redwood’s lunch and breakfast cost $3.40 and $1.49 more than the national average, respectively.

To further emphasize this problem, schools near Redwood have drastically lower prices for food. Just across the bay, students in San Francisco pay $3 for lunch and $1.50 for breakfast, according to the San Francisco Unified School District. In the Novato Unified School District, students pay $3.50 for the full-priced lunch and $2.25 for breakfast. The lunch, similar to Redwood, comes with milk, fruit and vegetables. Redwood should follow the lead of these high schools around the Bay Area and Marin by making meals more affordable.

However, having high meal prices is not entirely Redwood’s fault. The Hunger-Free Kids Act passed by the Obama Administration in 2010 requires schools to use whole grain products and reduce sodium, as well as provide vegetables, fruits and non-whole milk with school lunches. This act not only forced schools to increase the price of their meals to cover the costs, but also decreased the flavor in their menus.

Junior Noah Arias works in the CEA and is involved in seeing how the food is bought and sold. According to Arias, it is expensive for the CEA to buy ingredients because they are using organic and wholesome products.

However, the Trump Administration recently rolled back the Hunger-Free Kids Act, which will be effective starting in the 2018-2019 school year. Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue was in support of this action.

“[Schools] want to offer food that students actually want to eat. It doesn’t do any good to serve nutritious meals if they wind up in the trash can,” Perdue said.

Once the rollback is in effect, states can grant exemptions to schools regarding whole grain standards, current sodium reductions will be postponed for at least three years and schools will be allowed to provide one percent milk.

Along with Redwood, both Drake and Tamalpais High School charge the same amount as Redwood for breakfast and lunch. If students have to pay more than double the national average, then the food quality should be excellent, or acceptable at the very least. In reality, the food quality is unsatisfactory at best.

Sophomore Matt Millard frequently eats at the CEA, despite limited praise for its food.

“If you get the Asian food, there’s not enough meat. The pizza is way too greasy and the fries taste soggy and like cardboard,” Millard said.

Freshman Selena Marmolejo has similar views to Millard and the quality and price of meals at Redwood are affecting her academically.

“[The CEA food] is greasy and gross and it’s so fake and artificial-tasting. I don’t eat lunch here because of that and I don’t think it’s worth the price. Instead, I go off campus but then I get to school late. If the food was better here I would eat [at the CEA] more often, which would help me at school,” Marmolejo said.

According to the March Bark self-reported survey, just 10 percent of students are comfortable paying for what they receive in the CEA. This pales in comparison to the 39 percent of students who are not comfortable paying for what they receive and the 28 percent of students who are moderately comfortable paying for what they receive.

Hopefully the rollback of the Hunger-Free Kids Act will alleviate the cost of making school lunches, so the CEA will have no excuse for having such high prices. While they won’t have to stick to harsh guidelines nutritionally because of the new plan, they can hopefully still continue to generate healthy food. The overall impact of this rollback is that the cafeteria does not have to buy such expensive products for their food but can still make healthy and high-quality meals.

In order to enhance the appeal of cafeteria food, the CEA needs to lower its prices to match comparable schools’ lunch prices such as Novato’s $3.50 lunches. With the recent repeals by the Trump Administration, Redwood must make changes to the CEA not only to satisfy its students, but also to help them succeed. This will not only benefit the CEA by increasing business, but it will encourage a better learning environment at Redwood. If Redwood truly cares about nurturing its students so that they can flourish in their futures, then reform needs to happen.