Senior “Julie” knew their relationship was over the moment he struck her face. She and her boyfriend had been sitting on his bed, watching a new TV show on Netflix.

“He was talking to me about something, and I got distracted by the show that was playing. And he was like ‘Why aren’t you paying attention to me?’ And I looked up and he slapped me across the face,” “Julie,” who requested to remain anonymous, said. “I just curled up in a ball and cried, and he was like ‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m sorry.’ Eventually, I got up and walked home.”

Julie’s story is not an uncommon one in Marin County. Domestic violence is the number one violent crime reported in Marin, according to Center for Domestic Peace. What Julie experienced was dating violence, a more specific form of domestic violence that is inflicted by an intimate partner. It is defined by the National Center for Victims of Crime as controlling, aggressive and abusive behavior in a romantic relationship.

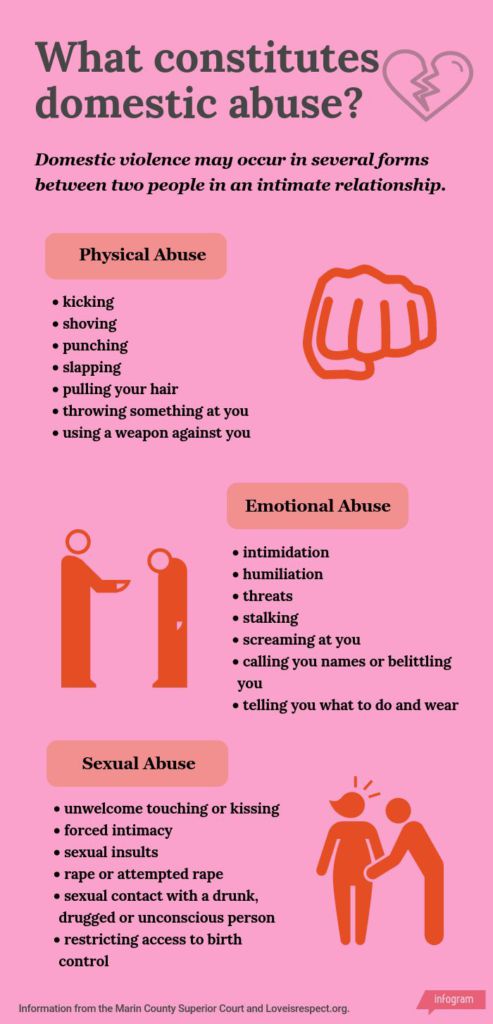

Controlling behavior includes actions like preventing a partner from hanging out with friends, telling him or her what to wear and constantly contacting the partner about his or her whereabouts, according to the National Center for Victims of Crime.

According to Loveisrespect.org, an organization founded by the National Domestic Violence Hotline that advocates healthy relationships and educates teens about dating violence, almost 1.5 million high school students nationwide experience physical abuse from a dating partner in a single year. One in three teenagers is a victim of physical, sexual, emotional or verbal abuse from a dating partner.

Julie said her relationship with her boyfriend, who was three years older than her, had begun positively. Then, she noticed that their dynamic was beginning to change around three months into their relationship.

“It started out fine. It had the typical relationship phases; the honeymoon phase was nice. And then around January of last year, it just started becoming a little strange, in the way that he was becoming possessive of my time,” Julie said.

She said she began giving in to his demands that she had to spend all of her time with him, feeling like she had to put her own needs second. She wasn’t able to hang out with other people and lost many friendships. Her school work fell behind. She said she began to feel guilty when she wasn’t able to provide for him what he expected of her.

“He was very nitpicky about the way that I acted and the way that I communicated. If I didn’t text back within 15 minutes, he would just assume that I was ignoring him or upset with him. If my immediate priority wasn’t him 24/7, he would take offense,” Julie said.

It finally got to the point where she had to tell him that she needed some space, but he took it the wrong way. Julie said they started fighting and when angry, he would throw objects.

“We would get in a fight and he would get really upset and escalate it, and he would chuck a phone at the wall or throw a book, and there were some times when they would just narrowly miss me and hit the wall behind me. It was very jarring,” Julie said. “You immediately understand, ‘I am not safe in this environment with the person that I love.’ And it’s just f***ing scary.”

The day he slapped her, she decided to break up with him. Julie said it was extremely difficult for her to end the relationship because she still cared for him.

“I was able to realize earlier on that there were unhealthy signs present, but I adored him,” Julie said. “I adored the guy. And it just didn’t seem to matter.”

Julie said she knows other students in the Redwood community who have been in similar situations; however, she said she believes that there is a misconception among students about the prevalence of the issue as they are unaware of what determines abuse.

“I think people at Redwood would look at abuse on the extreme side. They only think of it—they’re taught of it—as something that manifests itself through physical aggression, through physical bruises on someone’s body,” Julie said. “But what I’ve seen my own friends go through and I’ve gone through myself is emotional abuse, and that can be just as harmful, or maybe even more harmful, because the damage isn’t apparent.”

Julie hopes to see more educational initiatives at Redwood to increase awareness about what abuse is and how to face it.

Three male students at Redwood have taken on a seemingly Herculean task: addressing the culture of dating abuse within the Redwood community and attempting to break the silence that has shrouded it for so long.

Sophomores Matthew Millard, Scott McWhorter and Cole Panzardi are members of Marin Against Youth Abuse (MAYA), a youth-led program run by Center for Domestic Peace that seeks to educate teens on how to recognize the signs of dating violence and how to deal with abusive situations. Center for Domestic Peace is a San Rafael based social services organization that offers aid, shelter and resources to victims of domestic abuse.

According to Millard, topics of dating and domestic violence are not discussed enough at Redwood. He believes that due to the lack of information, teens who are in abusive relationships might fail to recognize the fact.

“While there are relationships at Redwood, people don’t really talk about what’s happening,” Millard said. “Maybe they don’t know that they are being taken advantage of, that there’s a pattern of control in the relationship.”

According to the Marin County Superior Court, physical abuse includes any action that hurts your body and sexual abuse consists of unwelcome touching, fondling or forced intimacy. Emotional violence constitutes using coercion, threats or anger to create a controlling and fearful relationship.

McWhorter, after experiencing domestic abuse in his own family life, joined MAYA to raise awareness about the issue. He argues that the ignorance surrounding abuse makes people more vulnerable to the abuse itself.

“I think teens in high school are desensitized to the real issue and they don’t understand what’s dating abuse and what’s not dating abuse,” McWhorter said. “So, a lot of times, they can conform to the demands of their abusive partner.”

According to Julie, ignorance plays a part in both the victim and the abuser’s role in a domestic violence situation.

“Ignorance manifests itself in the victim as denial, just thinking, ‘These things aren’t happening and these things aren’t detrimental to me because I don’t want them to be,’” Julie said. “On the abuser’s side, there is a level of entitlement that they think they have in the relationship and they’re willing to do whatever to maintain that. They’re ignorant of their significant other’s feelings.”

Meghan Kehoe, the Children, Youth and Community Prevention Division Manager at Center for Domestic Peace who heads MAYA, said she believes that youth-directed programs like MAYA are the best way to educate teens about domestic violence.

“Having young people speak to each other about this message is heard very differently than it is, say, if I, as a provider of services, were to come in and give a presentation. We trust who our friends are,” Kehoe said.

Millard, McWhorter and Panzardi are planning to start a MAYA committee club at Redwood this year, through which they will hand out educational flyers to students and present about what constitutes emotional, physical and sexual abuse.

MAYA is one of several programs directed by Center for Domestic Peace. Founded as Marin Abused Women’s Services (MAWS) in 1977, the organization started as a shelter to allow victims of domestic violence to flee abusive environments and have a safe, secret place to stay.

Though domestic violence is the top violent crime in Marin, 48 percent of students self-reported that they didn’t know if domestic violence was prevalent in Marin, and 24 percent self-reported they did not think it was prevalent in a recent Bark survey.

On a national scale, domestic violence is ubiquitous. According to the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, nearly one in four women and one in nine men have experienced sexual violence, physical violence or stalking by an intimate partner. One in four women and one in seven men have experienced severe physical violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime. Fifty-two percent of women and 17 percent of men have reported experiencing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of domestic abuse.

Redwood parent Mary Jane Elliott has been on the board of Center for Domestic Peace for three years. According to Elliott, there is a greater social stigma in Marin when it comes to domestic violence that inhibits victims from reporting their abuse.

“For upper-middle-class women and upper-class women there’s more of a social stigma and they have more barriers to coming [to the shelter] because psychologically they think, ‘I have everything, I’m educated. How can this be happening to me?’” Elliott said. “So they go a little bit into denial and the social stigma is such that they think this only happens to poor women.”

Center for Domestic Peace aims at spreading awareness, offering comprehensive resources to abuse victims and trying to make help more accessible despite that stigma.

One resource is the organization’s bilingual hotline, available in English and Spanish, that victims can call for help. If a victim is in a life-threatening situation, Center for Domestic Peace will make arrangements to transport the victim secretly and securely to a confidential shelter where the victim can seek asylum from his or her abuser and receive support.

In addition to the shelter, the organization provides transitional housing to those who qualify. According to Elliott, victims can live for up to 18 months with their children, if they have any, and receive access to psychological therapy, help with job resumes and applying to schools.

“[The transitional housing program is] just an amazing idea because you give them the tools to succeed for the rest of their lives,” Elliott said.

One of the programs pioneered by Center for Domestic Peace called ManKind trains violent men in Marin to “unlearn” their abusive patterns to end the cycle of violence.

According to Donna Garske, executive director of Center for Domestic peace, at least 60 percent of men that participate are court-ordered, meaning that they have been arrested for battery and are mandated to attend the program. Last year, 115 men participated in the program.

Garske said she believes that the deeply instilled system of patriarchy is what continues to allow society to cultivate domestic abusers.

“There’s no young boy that ever was born naturally abusive and violent. It’s a process and happens over time,” Garske said.

The phrases that boys grow up hearing—“be a man,” “don’t cry like a sissy” and “toughen up”—teach them from a young age that expressing emotions and vulnerability is unmanly, according to Garske.

“It creates a toxic self-image of what it means to be a man. And what violence does is help maintain that image of themselves,” Garske said. “So, they use violence to maintain the sense that they’re in charge, and they use control as a way to maintain that superiority over another person.”

According to Garske, a way to break the tradition of patriarchy and abuse is to stop treating girls and boys differently and by removing the pressure on young boys to express their masculinity in a certain way.

If you are experiencing domestic abuse or simply want to talk about your relationship with an expert from Center for Domestic Peace, call their hotline at 415-924-6616.