Data reveals Redwood has highest truancy rate in the district

By Kendall Rhoads and Amanda Trusheim

It’s test day. The study guide was handed out exactly two weeks ago, and the students were made fully aware of the upcoming exam. Yet when the tardy bell rings, only 11 of the 25 students are present.

One day later, the bell rings, indicating the beginning of SMART period. Once again, over half the class is missing.

Upon checking attendance records, the teacher discovers that most students attended every other period and that their absence had not been excused, an increasingly common trend at Redwood.

As the new school year begins, scenarios like these have been bemoaned by teachers and staff. Last year, Redwood had the highest truancy rate of any school in the district, according to Principal David Sondheim. Throughout the past four years, there has been an increased amount of excused and unexcused absences across all grade levels.

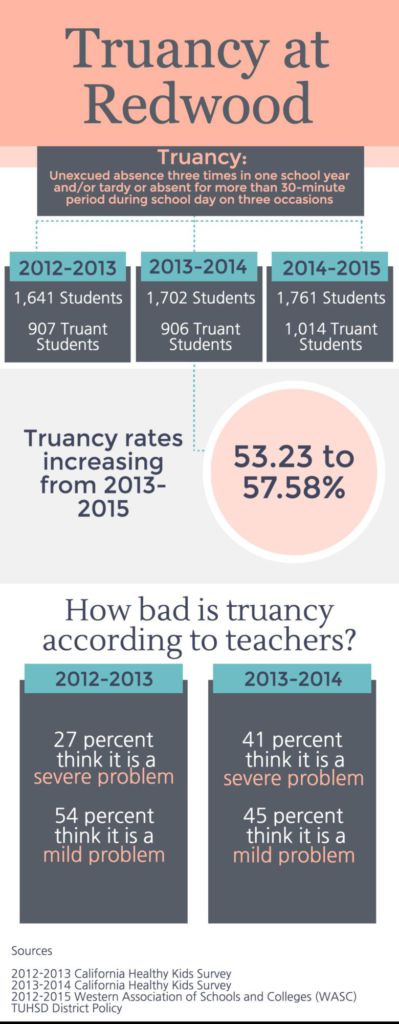

Truancy is defined as when a student “is absent from school without valid excuse three full days in one school year or tardy or absent for more than any 30-minute period during the school day without a valid excuse on three occasions in one school year, or any combination thereof,” according to the TUHSD district policy.

According to the latest Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC) reports available from the 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 school years, the truancy rate at Redwood has increased from 53.23 percent to 57.58 percent, surpassing both Tamalpais High School and Sir Francis Drake High School.

Throughout Sondheim’s eight years at Redwood, he has seen a dramatic increase in unexcused and excused absences. While Redwood is well below the current truancy rates of other schools in California, Sondheim believes that unexcused absences negatively impact student learning.

“[The administration] is all looking for ways to get students in class as much as possible. So when they miss class, we are trying to find ways for them to still be able to learn,” Sondheim said.

In 2014, the Redwood administration formed a committee to come up with solutions to solve the issues regarding attendance, according to Sondheim. Made up of several teachers, the group meets occasionally to discuss reasons for absences and ways to solve these problems.

While some possible solutions involved consequences such as punishment and loss of credit, the committee felt that rewarding students for good attendance was a more efficient way to promote attendance, according to Sondheim.

However, despite the teachers’ best efforts, many students still choose to ditch.

Alumnus Parker Laret, who graduated in 2016, often ditched school throughout his junior and senior year.

“I skipped classes junior year but then at the start of senior year, first semester, I skipped 108 classes, so that was the main part of my ditching. Then second semester I didn’t go at all,” Laret said. “All my friends were ditching and we had better things to do than be at school, and I just didn’t want to be in class.”

As Laret began to ditch, he was aware of the potential consequences he could face.

“I knew [teachers] would react badly. My history teacher handled it okay. My English teacher did not. I knew [admin] was going to get angry but I didn’t really care and wouldn’t listen to them. So I just ditched,” Laret said.

Due to Laret’s consistent absences, he was unable to walk at graduation.

“I tried to excuse my absences and then [Assistant Principal LaSandra White] took away my privileges from me when I turned 18, so then [the absences] were mostly unexcused,” Laret said.

Senior Peter Cline, who often ditched class his junior year, accredited his unexcused absences to a feeling that they wouldn’t negatively affect him in any significant way.

“Freshman year you kind of think you’ll get hunted down and that it’s a big deal but as you get more used to Redwood you realize unexcused absences aren’t that big of a deal considering how many kids get them,” Cline said.

Cline said he usually ditched about three to five class periods a week last year.

“I didn’t see the practical value in most of my classes,” Cline said. “There’s no way I’m going to need to find the area of a triangle later on in my life.”

When not in class, Cline said he would work out, get food or do homework for other classes.

While Cline said he received threats about his attendance from administration, no further action was taken, although he said he did receive some “snarky” comments from several teachers.

Last year, Cline was caught attempting to call himself out as his own parent, resulting in the school emailing the parents asking to confirm the absence. Afterward, Cline accepted the unexcused absences.

Although he experienced no repercussions, Cline said he wished he had acted differently last year.

“If I could go back to last year, I definitely would have ditched a lot less. However, I don’t think it will have a large impact on my life,” Cline said.

Cline has new plans for the upcoming year.

“I’m definitely going to ditch less, mostly for my parents’ sake and the senior in good standing policies. I also want to be able to walk at graduation,” Cline said.

As students began to ditch more frequently, teachers acknowledged the severity of the issue. Nineteen percent of TUHSD staff members believed truancy was a moderate to severe problem in 2012, according to the California Healthy Kids Survey from that year. By 2013, that number went up to 45 percent.

“Ditching is interesting because it shows up as an unexcused absence. We all know that ditching includes when someone is calling in an excuse for you. We know we have significant number of parents who will call in for their kids, or students who will call in as their friends’ parents, etc.,” Sondheim said. “That’s why our concern is larger than just unexcused absences.”

Administrators are hoping to counteract this by keeping parents as informed as possible, according to Sondheim.

“One of the desires for me as principal is to send more messages home to parents enforcing how important attendance is,” Sondheim said.

On Aug. 29, Sondheim sent out an email to all student guardians regarding attendance. In this email, Sondheim stated that good attendance is an administrative goal this school year in order to ensure academic achievement.

In the email, Sondheim wrote, “The point is that regular school attendance is very important and we expect all students to be in school every day. Poor attendance is not just about unexcused absences or students willfully not attending class.”

Ann Jackson, Redwood’s attendance clerk, said there are several ways students try to excuse their absence, but calling in is the most common.

“There always seem to be students who try to call themselves in or sign their parents’ names. I can often tell right away, and if not, I contact a parent to confirm the note,” Jackson said.

These strategies are often seen during the spring when “senioritis” and “spring fever” hit, according to Jackson.

The administration is working on trying to find new ways to prevent students from ditching classes.

“We all want students in class as much as possible and you cannot have the same learning opportunity when you miss classes as you do when you’re absent,” Sondheim said.

Redwood teachers have noticed the increase in absences, and some are modifying their policies in an attempt to resolve the issue.

Marta Di Domizio, a science teacher, has decided to change her personal attendance policy from previous years to the current district policy as she observed students being irresponsible with absences and tardies in her class.

“It wasn’t really the fact that Redwood is number one in absences that affected [the policy change], it was more that what I saw last year was a few students being absent very often or being tardy very often and this affected their learning a lot,” Di Domizio said.

Di Domizio said she had students who ended with Cs, Ds and Fs due to their low rate of attendance. If students had gone to class and been on time, they would not have failed the class.

According to TUHSD policy, “a teacher may lower a student’s grade a full grade or assign a failing grade if the student has four or more unexcused absences.” However, this policy is largely no longer enforced at Redwood.

With the absence of summer school, Sondheim thought that the grade reduction would be too much for students. Because the school is not following that policy, new methods of truancy prevention have been researched.

However, some teachers choose to follow this policy, while others refrain from lowering a student’s grade based upon attendance.

“I wasn’t in class so my grades started going down, but I was able to keep my grades decently high without going to class if the teacher didn’t take away points,” Laret said.

Students decide to ditch school for a variety of reasons. While some kids leave class to mess around, others are missing school for reasons linked to stress, according to Sondheim.

A 2014 CA Healthy Kids Survey showed that 32 percent of Redwood students in 11th grade ditched class because they felt like they weren’t prepared for a test. Thirty-one percent felt as if they did not get enough sleep to come to class and 16 percent were bored and uninterested.

In 2012, 14 percent of Redwood ninth graders ditched school once a week and 2 percent of 11th graders ditched school once a week, according to the CA Healthy Kids Survey. In 2014, 20 percent of Redwood ninth graders ditched school once a week and seven percent of 11th graders ditched school once a week.

“I think of attendance as a community issue, not just a school issue,” Di Domizio said. “It’s a combination of the school, the students, and the parents all being on the same page.”