For a growing number of Redwood students, finances are playing an important role in college decisions instead of merely choosing between acceptances. According to a May Bark survey, 31 percent of students say that concern regarding student debt will influence their college choice.

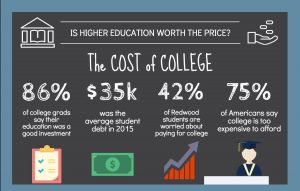

This reflects a growing concern over the sharp rise of student debt. The average national student debt for the class of 2015 was the highest ever at $35,000 per student, according to the Wall Street Journal.

AP Economics teacher Paul Ippolito, who worked on Wall Street before turning to teaching, sees the rise of student debt as a problem both locally and nationally.

“Student loans are now up to $1.3 trillion dollars; that’s how much this generation has borrowed. It is a potential bubble,” Ippolito said. “It’s bigger [per person] than any credit card debt, car loan debt; it’s bigger than all debt except the mortgage on your house. So we have a student loan crisis.”

Attitudes regarding college and the job market have shifted significantly since the 2008 financial crisis, as his students realize that paying for college and finding a job is not as easy they previously thought, according to Ippolito. This trend is reflected in the larger Redwood student body, as 42 percent of students are worried about the financial burden of paying for college.

“I have many more students going to College of Marin (COM) or another community college, even though they’re brilliant kids, and then their plan is to go to [UC] Berkeley or UCLA,” he said. “I think that’s a great move, but you lose that social aspect of freshman and sophomore year, which is sad. Kids are more concerned [about the future] than I’ve ever seen.”

One of these concerned students is senior Kylie Potter, who will be paying her own college tuition. Potter was waitlisted at UC Davis and accepted at both UC Merced and Sonoma State, but is attending community college for two years and then transferring to a state school for financial reasons.

“I would want to go to Sonoma State or Davis, but I don’t have $30,000 to pull out,” Potter said.

According to Potter, she is ineligible for some forms of financial aid because of certain rules of the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), which includes parent income in its aid estimation even if parents are not financially contributing unless an applicant declares financial independence, which is typically only possible in extreme cases.

“My dad’s income was high enough that I don’t qualify for grants like the Cal Grant or the Pell Grant, but he’s not contributing,” Potter said. “So it says that my estimated family contribution should be $13,000 a year and obviously I can’t do that on my own.”

That leaves Potter with the option of either applying for student loans or attending community college.

“I’m going to see how much help I can get from scholarships, but if I were to go away I would have to pay with 90 percent loans, which would not be ideal,” she said.

Potter believes that the freshman year of college is mainly valuable as a social experience.

“Going away to college right away is just for the experience of living on campus and the social activities because you’re really taking basic classes, at least for the first year,” Potter said. “$30,000 is a lot of money to pay just for a social experience.”

Stephen Hart, an economics and freshman social studies teacher, graduated from the University of Michigan with an undergraduate degree in 2012 and then went on to earn his master’s degree in teaching in 2013, acquiring $125,000 in student-loan debt.

“I had to support my own education financially and was expecting to come away with some student debt, as most people do,” Hart said. “But it is a significant amount of money, and to step back and think about how much money I give per month, how much total with interest over the 10-year period, it can seem very crushing or burdensome just to think about the amount of money you still owe.”

Hart didn’t anticipate taking out so much money, as he expected financial support from his parents, but the 2008 financial crisis significantly impacted his family.

“The intention was that I wouldn’t have taken out anywhere near as much as I did simply because the idea was that my parents were going to foot some of that, and that didn’t end up being the case,” Hart said.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, student debt in the United States has almost doubled, according to a report by the U.S Department of Education. In 2008, the average student debt was approximately $18,000.

“Today, kids are graduating with $30,000 in debt on average, so it’s doubled in eight years. That’s a scary trend,” Ippolito said.

Another factor in America’s student debt crisis is the increase in tuition. College tuition has been rising almost six percent above the rate of inflation, according to the University of Massachusetts.

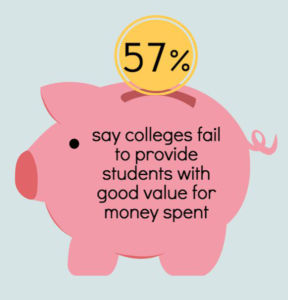

While the exact cause of this increase is due to a combination of factors, several major issues include expansion of federal aid, decreased federal funding, and increased spending on faculty, administration and amenities, according to the Department of Education’s Postsecondary Database. This does not necessarily mean improvements in curriculum or smaller class sizes, according to Ippolito and Hart.

“Class sizes have gotten bigger, and pretty much everywhere it’s been measured, quality of education has gone down and you’re paying more than ever,” Ippolito said. “Part of that is that they’ve built these fancy dorm rooms and these really nice gyms and a great food program. You have facilities we never had.”

Another influence in tuition cost is the rise of hiring non-teaching staff, such as administrators, according to Ippolito.

“Probably the universities are too top heavy, too many administrators and not enough professors,” Ippolito said. “Class size has gone up, so it hasn’t been as if they’ve been hiring for more teachers, you’d see smaller class size, then it would make sense. I would say a lot of the issue is the infrastructure.”

Hart also mentioned that tuition at Michigan did not seem to be contributing to smaller class sizes.

“A lot of my classes were pretty big,” Hart said. “At Michigan, generally speaking, if you take a class there’s a lecture session you go to twice a week and my basic economics classes could be 300 people all in one room or even more for certain classes.”

However, Ippolito questions whether these campus additions are worth the significantly increased price

tag.

“You’re not paying for education, you’re paying to be more comfortable on campus,” he said. “Is it worth it?”

Both Hart and Ippolito believe that, though a college education is overpriced, it is generally worth the cost. A recent Pew Research survey showed that 86 percent of college graduates say their schooling was a good investment.

“I know that I wouldn’t be where I am right now without the education and degrees that I have, so I understand that getting the education level that I got was necessary to be in a very fortunate situation like I am now,” Hart said. “But there were times when you think, ‘What is $60,000 for every person I see here right now going towards?’”

The primary reason Ippolito believes higher education is valuable is because of the edge it provides in the job market.

“I think college is still worth it. Statistics show that you’re much more likely to be employed if you get a college degree than a high school degree,” he said. “Unfortunately, college graduates are taking jobs that high school graduates used to take.”

Pew Research data also supports that higher education is profitable in the long run. According to a 2012 survey, the average college graduate earns $650,000 more in a lifetime that someone with a high school degree.

However, Ippolito said that student debt can have an impact on the economy that reaches further than just the education sector.

“It’s not good when young people graduate in debt because, what don’t they do? They don’t buy cars, they don’t move out of their parents’ basement, they don’t get their careers started, they don’t get married, they don’t have kids,” Ippolito said. “And if you look at your generation, all those statistics, we’ve never seen numbers so low for buying cars, moving out of homes, getting married, having kids and part of that is the debt.”

Hart also mentioned the effect his debt will have on his immediate economic future.

“The idea of me getting a house or any piece of real estate is not going to be feasible until my loans are paid off. I’m basically paying a small mortgage payment to student loans every month,” he said. “The larger purchases are not going to happen for quite a while.”

Fortunately, Hart is on track to repay his loans within the 10-year period before the interest rates adjust, as all of his loans are federal with the exception of one higher-rate private loan.

“I’m lucky that I’m going to be able to pay it off in 10 years, some people take 20 or even 30 years to pay it all off,” Hart said. “I’m not worried about it simply because I have a very good and stable job and income that I can depend on, and therefore I know that as long as I’m working I’ll be more than fine.”

However, although Hart’s situation is stable, the amount of money he has to repay can still be a burden.

“I’ve already been paying for over two years, and you still see that amount and think ‘Is that amount even changing?’ It can be very overwhelming at times,” he said. “ I can’t imagine what it’s like for other people who have as much debt as I do or more, and not knowing where that next payment will come from.”

While Hart remembers his time at Michigan fondly, he also questions whether a different route could have led him to the same point in his career.

“Sometimes you’ll meet people who didn’t go to anywhere as near expensive as a school, and they’re in the same position you are in terms of jobs and salary, so at the times you ask, ‘Was it worth it?’” Hart said. “Maybe it would have been better to take the junior or community college option and transfer or to consider other opportunities. Maybe it would have been better for me to go to a not as great school, but stay in state instead.”

Potter also thinks that the community college route is just as valid as a four-year education plan, although it is not always recognized in the Marin community.

“I hate that many kids in Marin have a negative attitude towards COM. They look down on it, which I think is really disrespectful because it’s not like I’m an idiot or don’t have good grades or don’t do well in school,” Potter said. “Sometimes your situation with your family or your finances just doesn’t work out the way you want it to.”

Potter also considers COM a good option because she doesn’t have the money to try various options in case the first one she tries isn’t the right fit.

“A lot of people in the past couple years from Redwood have gone off to school and either not liked it or not done well and had to come home anyway, so COM is nothing to be ashamed of and shouldn’t be disrespected,” Potter said. “Going away right after high school and paying $60,000 and coming home anyways doesn’t make any sense to me.”