Hands allow people to communicate emotions, commands, and ideas to one another. For 21-year-old Theo St. Francis, however, they are a sensitive topic.

“The hands are hugely tied into how we relate to our environment. They were designed

to allow us to

manipulate things and to change our environments and to express ourselves,” St. Francis explained. “I

just saw early on that whether or not I was going to be able to get back on my feet and run and do all these things, if I could move my fingers totally fine, I would be able to type and write code and manipulate objects and just like do basic things, even if it was from a seated position.”

When St. Francis was a student at Marin Academy (MA), he swam for his school team as well as for North Bay Aquatics, where he befriended some Redwood peers. Despite living in Sonoma, St. Francis managed to get to Redwood at 5:30 every morning to swim before before arriving at MA on time for school and then participating on his school’s swim team, eventually captaining it his senior year.

St. Francis had committed to Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to study engineering. Physics, especially aerospace, enthralled him, and he arrived on campus in August of 2013 ready to partake in pre-orientation activities. However, his future was suddenly snatched from under his fingertips on the last day of pre-orientation when he fractured his C6 vertebra during a diving accident in a designated swimming area on a beach. By the time classes began for the fall semester, St. Francis was struggling to accept the doctor’s diagnosis that he would never walk again.

In fact, St. Francis never did accept this diagnosis. He could still feel every limb, every muscle in his body, but just couldn’t control most of them. However, he set the huge goals of returning to school and living on his feet again, and has been reaching them one step at a time.

Above, a video of Theo St. Francis showing his progress as he relearns to walk. Below, he trains with a machine to mimic a perfect walking gait. Both videos are courtesy of Theo St. Francis, from his blog www.theovercoming.org.

He was particularly inspired to overcome his injury by a friend he made while hospitalized who, despite suffering a “very complete injury,” resumed his medical residency because he had complete use of his arms, allowing him to assist in surgeries and other procedures.

“Within just weeks of being injured, he was right back to his residency actually right at a hospital in Boston, and was very shortly thereafter installing pick lines and sutchering and doing all these things—from a wheelchair—but doing them,” he said, smiling.

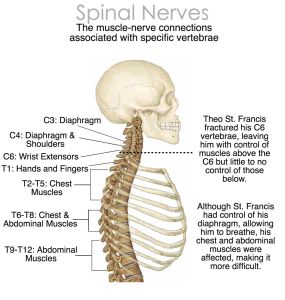

The C6 vertebrae controls the wrist extensor muscles and innervates the biceps. However, a spinal cord injury of the C6 will impact much more: paralysis in the hands, trunk and legs are common, and despite control of the diaphragm and wrists, C6 spinal cord injuries leave little untouched.

St. Francis retained control of his deltoids, biceps, and some forearm muscles, allowing him free use of his arms. He counts himself as lucky for not having injured a vertebra higher up.

“It was a totally fluke incident, and because of that, I could have broken a higher vertebra,” St. Francis said. “For example, the diaphragm, the primary breathing muscle, is innervated by the nerve roots that come out of C3, C4, and C5.”

He continued to explain that despite the fact that other muscles involved in breathing were impacted because they are innervated by lower vertebra, he always had control of his lungs, allowing him to survive in the water and live without a trache for machine.

St. Francis’s engineering mindset has helped him understand his condition and explore novel treatments to repair the “biological machine” that is his body.

“In my experience it’s helped tremendously to understand what’s going on [with my body],” St. Francis said. “Even a joint slightly out of place or slightly irritated can impact my neurologic connection to it quite a bit. I’ve read quite a few physiology books and I’ve picked the brains of people in [physical therapy] a lot, saying, ‘What is this’ or ‘How is this movement different from that, and what should I be paying attention to.’ I think it’s a good thing to be really engaged in that way with understanding your own body.”

Through various friends, St. Francis got in contact with Alejandra Monsalve, a physical therapist who specializes in a new form of pilates called Neurokinetic Pilates, to undergo physical therapy with her. Neurokinetic Pilates aims to use fascial lines of connective muscle tissue to support the body after spinal cord injuries and establish new connections between the muscles and the nervous system.

“It’s actually much less in the body and much more in the practicing new neural pathways to say, ‘Okay, the highway down the spinal cord, there is a traffic jam there. We’re not going to go through there, we’re going to take this detour along this connective tissue,’ and then ‘Brain, I want you to do that every time I send a message,’” St. Francis explained, stressing that through repeated movements he and his trainers are establishing automatic nerve-muscle responses when prompted. “The exercises that we do are very positionally dependent, so we focus a lot on putting the body in the position to physically feel that fascial line…The exact position every joint in my body is in is crucial because [when] the brain remembers the movements, the position of the joints is recorded with that movement.”

Above, a video created by one of Theo St. Francis’s gyms depicting his overall progress since his injury. Video courtesy of Theo St. Francis from www.theovercoming.org.

Alejandra developed the method after sustaining a spinal cord injury of her own. St. Francis acknowledges that the practice is very new and localized but strongly believes that it is the new frontier for spinal cord injury therapy.

His pilates-based therapy is very different to the activity-based therapy to which he was originally exposed.

“I would describe the activity-based [therapy as] much more closely aligned with crossfit for people with spinal cord injuries. It was so good for me to get moving again and be able to sweat and move around, and I did regain a lot of function,” St. Francis recalled. “I think that function was kind of finding these old neural pathways which had been preserved through the injury, and using my body to feel the movement so it can find those. But it is not making new pathways, which is what I’m doing with pilates.”

St. Francis works with another physical therapist, Kinley McCracken, who comes to his house to do pilates-based training. According to McCracken, working with St. Francis has been “absolutely amazing.”

“I’ve never worked with somebody who’s so interested in learning every aspect of his body and I find that it’s a real collaborative effort between us figuring out what he needs to work on and how we’re going to work on it the best,” she said.

McCracken has always believed in St. Francis’s abilities to reach his goals. However, only recently has she seen a mental shift in the way he approaches his recovery.

“He’s always been determined and he’s always said, ‘this is going to happen no matter what,’” McCracken said. “But I do think recently he’s become a little more open to the process and being able to really focus on the goal in front of him instead of allowing that further big-picture goal to be his main focus every day.”

An example of new versus old connections can be found in his legs. Over the course of several months after the accident, St. Francis slowly regained sensation in his toes and legs.

“I can feel the wind on my legs, which is a really small thing but at the same time it’s like, that’s big!” he said. “When you’re outside and you’re able to feel that, that’s you participating in the environment, that’s you sensing.”

But despite his euphoria over the discovery that sensation pathways were still working in his legs, St. Francis was not able to send signals down along movement pathways, an obstacle that he still cannot explain.

St. Francis has dedicated hours to the tiny movements demanded by pilates training, and says that he has reaped massive rewards.

Above, a video depicting on of the many pilates-based movements that St. Francis practices every day at home. Video courtesy of Theo St. Francis from www.theovercoming.org.

With the pilates method, he has gained immense stability, to the point that he is able to conduct a full 90-minute long interview without slouching, falling over, or having any additional support, as he might have before, and has the ability to perform many basic movements without assistance from his trainers anymore.

St. Francis has begun to participate in various physically strenuous activities again. He has attended over half a dozen concerts in the past few months, competed in swimming races, and went skiing for the first time in January. While these activities might not compare to the extensive backpacking trips he took during his freshman year of high school or the ability to swim for hours a day without a problem, it represents a new beginning into a different but just as fulfilling life.

During a Kygo concert that St. Francis attended with a few of his therapists, he stayed standing for over three hours. Despite not being able to move much or do anything else, standing almost unassisted for so long was a milestone. But the most memorable moment happened before the concert began.

“We got to the concert pretty early and wound our way to the front, and I had [my therapists’] help standing up, and so people who filled in behind me hadn’t seen me come in in a wheelchair,” St. Francis recalled. “As they filled in behind, we got so many questions of ‘whose wheelchair is this, what is it doing here?’ because it was taking up space up in the front. I didn’t want it taken away because if I needed to sit down I wanted it to be there, but we were laughing so hard because people were so confused. I remember turning around one time and saying, ‘I don’t know, I don’t need it.’ And of course [people] didn’t know, but it was a good moment.”

St. Francis’s overall optimistic view of life has also helped him succeed at so many of his goals and adapt to his new normal.

“I have much less ability to adapt in the moment to things as I would have. When things go wrong, I will often have to get help as opposed to solving it on my own,” he said.

Backpacking serves as a perfect example in his eyes because you carry everything needed for survival on your back. “It’s just you and nature. That’s to me such a fundamental essence of earning your stay on this planet and being able to fend for yourself and handle whatever happens. I’m not as good at that now, because things are harder for me and I need to plan them out more, but as I get more able and more

dependent, the ability to adapt more in the moment is getting better.”

Perhaps the most visible markers of recovery have been the pieces of equipment that St. Francis received,

ironically on his birthday.

“The day of my nineteenth birthday, December 23, the medical supply equipment company sent a representative to fit the wheelchair to me. It was a Monday in 2013. And that was it was just kind of a

sick joke,” St. Francis recalled. “Then exactly a year later, the we installed this Galileo machine. It kind of to me signalled a shift in the the tone of recovery and coming to develop ways to get function back and kind of getting better at getting better.”