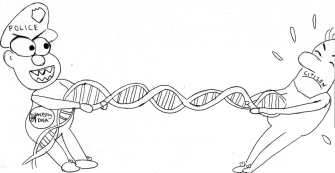

A genetic testing service gave a client’s genetic results to police without consent, falsely implicating the client to a murder-rape, a privacy advocacy group found.

Once implicated in 2014, the Ancestry.com client was detained and interrogated without a lawyer present, according to the Electronic Frontier Foundation. In the end, the police wasted many resources and hurt the reputation of an innocent individual. Clearly the police did wrong in trusting a business with the job of a forensics expert.

This case is just one example of why we should be wary of direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic testing. DTC genetic testing is a type of genetic test that directly links consumers to genetic decoders without going through a health care professional. Websites such as Ancestry.com, 23andme, and deCODEme are examples of DTC genetic testing businesses.

Eliminating the healthcare “middleman” seems great in terms of efficiency, but what else are you eliminating with it? Quality assurance and protection, for one.

Since our genetic information is not protected by any official body, our DNA may be used against us. Companies will continue to discriminate against individuals based upon certain genetic traits, police may wrongly incarcerate individuals due to genetic or hereditary similarities to wanted criminals, and healthcare companies may charge certain people more, citing “pre-existing conditions.”

Shockingly, the issue of genetic discrimination already exists today, the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) found.

Genetic screening “examines the genetic makeup of employees or job applicants for specific inherited characteristics” and is commonly used to discriminate against individuals, according to the DOL. A 1997 DOL survey identified 550 people who were denied employment or insurance based on their genetic predisposition to an illness.

This number has likely increased, as “15 percent of the 400 companies surveyed have planned, by the year 2000, to check the genetic status of prospective employees and their dependents before making employment offers,” a 1998 DOL survey found.

As it has in the past, DTC testing will put citizens at a disadvantage. We must protect ourselves from business, or else we could very well lose control over who sees and shares our genetic information.

Luckily, legislation was put in place to combat what is called “genetic discrimination.” The 2008 federal law, called the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act, “prohibits group health plans and health insurers from denying coverage to a healthy individual or charging that person higher premiums based solely on a genetic predisposition to developing a disease in the future,” according to the Department of Justice.

Acts such as those are strong first steps, but more detailed acts must be created to ensure full consumer protection.

Another issue with DTC testing is that most private genetic information is poorly protected by the decoding companies. Companies such as Ancestry.com have privacy agreements with loopholes that allow for data sharing in “extraneous circumstances,” meaning that the governmental bodies can access something as private as your genetics without your consent.

DTC businesses are rapidly expanding without bounds. Clearly, regulations on “genetic sharing” are desperately needed, as no strong federal rules exist in the current market.

Even more troubling, the Food and Drug Administration has yet to claim that the majority of DTC genetic tests are accurate, according to a recent FDA press release. Though there are hundreds of tests available, only a few are approved by the FDA. Approved devices are sold as at-home test kits, and are therefore considered “medical devices” over which the FDA can assert greater control.

Other types of DTC tests require customers to mail in genetic samples for testing. This makes it difficult for the FDA to regulate such tests, since the actual testing is completed in the laboratories of providers.

Although there are some benefits to DTC testing, such as the accessibility of tests to consumers and the promotion of scientific innovation, one must remember what is really at stake. We aren’t just talking about phone numbers or usernames––identities are on the line. We cannot let businesses spread misleading claims while secretly sharing our most sacred information.

Academic professionals have also rightfully advocated for greater “genetic protection.” Dr. David Hunter, professor at the Harvard School of Public Health, warned of such misleading claims in a recent report.

“Without professional guidance, consumers can potentially misinterpret genetic information, causing them to be deluded about their personal health,” Hunter wrote.

With our identities on the line, it’s up to the consumer to be wary of the consequences.