Only 33.8 percent of students at Redwood identify as feminist, according to a February Bark survey. Yet 88.8 percent of students say they believe there should be equality among genders in all aspects of life, according to the same survey.

Sophomore Audrey Gaither is in that majority. She said she believes in the equality of the sexes wholeheartedly, but doesn’t want to call herself a feminist because she thinks the movement has been misportrayed.

“I think feminism in general has been kind of misconstrued as female domination, females being more powerful than men, and I’ve also seen a lot of advertisements hating on chivalry and I kind of disagree with that,” Gaither said.

Gaither said she’s also been turned off by the stubbornness of the feminists she knows and the way that articles and feminist media tend to expose the problem of gender inequality without offering solutions for how to fix it.

“Lots of people who seem to be advocating for feminism aren’t very willing to change their views, which seems kind of counterproductive,” Gaither said. “It’s more about people venting about problems that they’re seeing without really having a plan on how to fix it.”

However, a person cannot believe in the definition of feminism without claiming the feminist label, according to Roxane Gay, author of the New York Times bestseller Bad Feminist.

“The word feminist is simply a succinct way of saying I believe in equal rights and the equitable treatment of women. Sometimes, less is more,” Gay wrote in an email.

For junior Ruby Elson, it was a simple choice to identify as feminist.

“I’m a feminist because I believe in the social, economic, and political equality of the sexes,” Elson said.

So why is there a discrepancy between those who identify as feminist and those who believe in gender equality?

According to social studies teacher Ann Jaime, many students simply don’t know the definition of feminism.

“It’s a very simple definition, and that makes it a little less scary,” said Jaime, who used to teach Women’s History. “When you describe what [feminism] actually is, which is equal rights for sexes…almost everybody goes, ‘Oh yeah, that makes sense.’ Nobody says a qualified women shouldn’t have access to whatever she wants to do.”

This lack of a clear definition comes from the media’s skewed portrayal of feminism, according to Nova Rivera, a feminist studies major at UC Santa Cruz and student representative for the department.

“Often, we are socialized to believe that feminists are coming from a place of man-hatred, also known as misandry, and that all feminists believe in the eradication of all men in the world,” Rivera said. “This is just a very untrue and cliche argument used to minimize feminists in order to write them off as overtly radical.”

Perhaps this association is why the word carries negative connotations for quite a large percentage of Redwood students, as Bark survey data showed. One in five students associate the word feminism with hating men, 10 percent associate it with being lesbian, and 8.1 percent of students associate it with being unattractive.

Elson said that the stigma that surrounds feminism has seeped into Redwood culture.

“Misogynists, who have tried to keep the movement down, have stigmatized the label ‘feminist’ to such a degree that it is now seen to the common media, the dominant media, that being a feminist is equated to being a crazy man-hating, radical anarchist liberal who doesn’t wear deodorant,” Elson said.

And a time when the pressure to conform is high, many high school students may not want to label themselves as something so seemingly extremist, Rivera said.

“It is not uncommon for people to be bullied for their beliefs, especially if what they believe in goes against popular opinion,” Rivera said. “We build up this idea of what a feminist looks like so that we can identify, label, and then proceed to react to someone who is what we have been taught to believe is feminist.”

Survey data further shows that 32.5 percent of students associate being a feminist with being politically liberal, despite feminists’ assertions that the two are not contingent on one another. While 37 percent of males associate it with being politically liberal, only 27.8 percent of females associate it with being politically liberal.

“It’s certainly possible to be politically conservative and be a feminist,” said junior Anabella Bazalgette, who adamantly identifies as feminist. “Political conservatism does not equate to total rejection of the equality of the sexes. I don’t think that conservatism and feminism are mutually exclusive.”

Boys and Feminism

While many girls may hesitate to call themselves feminists, it appears that boys at Redwood have an even harder time using the label.

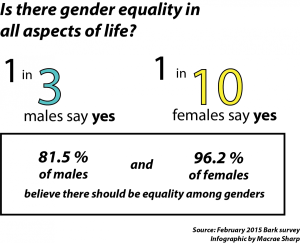

The February Bark survey found that only 17.3 percent of males at Redwood identify as feminists, whereas 50.6 percent of females do. The survey did not have an option for students to select non-binary genders.

Furthermore, 81.5 percent of males believe there should be equality among genders, in contrast to the 96.2 percent of females who believe there should be.

Junior Matthew Moser, who serves as the vice president of the Gay Trans* Straight Alliance, offered that boys at Redwood may not want to call themselves feminists because of the social implications of the “fem” in feminist.

“I think that for boys at this age, their masculinity is so fragile, and they’re so proud of it, that anything associated with being womanly or girly, they don’t want to associate with because they see it as being unmasculine,” Moser said. “But what’s more masculine than helping people and fighting for someone else’s rights?”

According to senior Ben Dreskin, the aversion to the label of feminism may be the result of negative associations with the word.

“Maybe identifying as a feminist is a sign of weakness to some. I don’t agree with that,” Dreskin said. “To me it isn’t even a question. It’s just genders are equal––there’s nothing more to it than that.”

Data from the Bark survey supports Dreskin’s theory about negative associations. Results show that 34.6 percent of males at Redwood associate feminism with hating men, whereas only 3.8 percent of females do.

Furthermore, 14.8 percent of males associate feminism with being unattractive, while only 1.3 percent of females do.

The quality of “being lesbian” followed a similar trend: 16 percent of males associate feminism with being lesbian, in comparison to the 3.8 percent of females who do.

The Need for a Label

With its myriad negative associations, some might propose that we discard the feminist label altogether and simply say we believe in the equal rights and treatment of women.

Moser suggested that people may choose to call themselves “equalists” if they’re in an uncomfortable situation.

“I think that by saying you’re an equalist, you’re not only saying you’re pro-women’s rights you’re pro-everyone’s rights, so it just depends on the situation you’re in,” he said. “As long as you’re fine with the cause, in the end I don’t care what you call yourself. You just need to support.”

But terms such as “equalist” or “pro-human rights” are too vague for Bazalgette, who said that the term “feminism” is necessary for the advancement of gender equality.

“The word ‘feminism’ has a specific and direct course of action, and that’s what we need. We don’t need something so ambiguous as an equalist because the problems facing our society today are mainly a result of the patriarchy,” she said.

Jaime noted that the label still has a place in modern society, despite its negative connotations.

“There are still so many pockets of sexism in this country that we don’t necessarily challenge. We sort of do the civil rights like, ‘It’s much better than it used to be, so that’s good enough,’” she said.