A Humvee is an armored vehicle built to transport soldiers across any terrain. It’s a five-ton fortress of reinforced steel and bulletproof glass, often topped with a turret for mounting a gun or a missile.

Humvees have been around since the 1980s, and they’ve been deployed everywhere from Iraq to Somalia to the Balkans to Afghanistan. Oh—and there’s also one a stone’s throw away from Redwood, at the Central Marin Police Department’s headquarters on Doherty Drive.

Central Marin received its Humvee “as a hand-me-down,” according to School Resource Officer Scott McKenna. Though a brand-new Humvee can cost up to $140,000, the police got theirs for free through the Department of Defense’s 1033 Program, which distributes surplus military equipment to local police departments.

The 1033 Program was created in the early 1990s to help community police departments combat drug trafficking. A few years later, it was expanded to include law enforcement agencies across the country with the goal of preventing terrorism and drug use.

Since its inception, the 1033 Program has distributed nearly $5 billion worth of military equipment to more than 8,000 law enforcement agencies that have signed up for the program, according to data released by the Pentagon in November. This includes $1.4 billion of “tactical military equipment” such as guns, grenades, helicopters, and Humvees.

The Central Marin Police has modified their Humvee for use in search-and-rescue missions—they painted it and removed some of the insides. Since the Humvee can go up to five feet underwater, it’s useful in the case of flooding, according to McKenna.

“We don’t use it for what it was used for in the military, which was armored transport,” McKenna said. “Even though it has a turret on the top of it, a gun turret, we don’t actually have the gun that’s attached for the turret.”

McKenna emphasized that the Humvee is an anomaly for the Central Marin Police Department.

“The weapons that we have for our department have actually been in our department for several years,” McKenna said. “For instance, the handguns that we use for our department have been issued for almost 20 years, if not longer. They haven’t gone out and bought new, crazy equipment.”

According to the 1033 Program’s website, “Law enforcement agencies use the equipment in a variety of ways. For instance, four-wheel drive vehicles are used to interrupt drug harvesting, haul away marijuana, patrol streets and conduct surveillance.”

The website does not specify what some of the other equipment has been used for, such as the mine resistant vehicles, helicopters, and Explosive Ordnance Disposal Robots. A robot and a mine-resistant vehicle currently reside in Napa, and the Sacramento County Sheriff Department has eight helicopters.

McKenna said that the 1033 Program allows the department to get equipment for free instead of using taxpayer dollars.

“If you don’t go through a program like this…there’s no way a department our size would be able to afford those things in the first place,” McKenna said. “As far as our department, we choose to make sure that the equipment that we have is functioning properly, and we’re good with what we’ve got so far.”

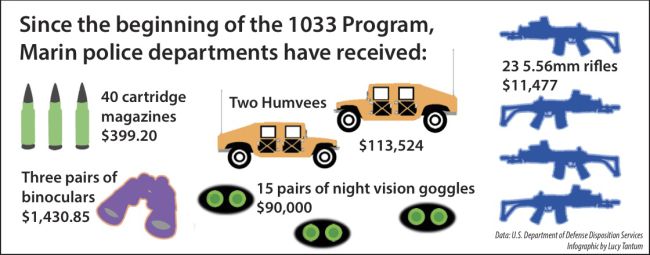

The Central Marin police department has received $75,511 worth of equipment since the beginning of the 1033 Program, according to data released by the Pentagon last fall. The Humvee and its turret comprise the bulk of this cost.

Other Marin police departments have also received various quantities of 1033 equipment. San Rafael has gotten $72,085 worth: one Humvee, one night vision sight, four silencers and 16 rifles.

Somewhat surprisingly, the Fairfax Police Department has received much more 1033 equipment than all other Marin municipalities combined.

Fairfax is home to, among other things, seven rifles, 15 pairs of night vision goggles, 22 reflector sights, and 40 cartridge magazines, according to the Marshall Project database. In total, the equipment is valued at a total of $242,274.

The Fairfax Police Department recorded 162 crimes in 2013, according to data from their website. That’s a ratio of almost $1,500 of military equipment to each crime.

The Fairfax and San Rafael police departments did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The distribution of military equipment has been happening for a while, but it was thrust into the public eye last fall when a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, shot teenager Michael Brown. During the protests that ensued, the Ferguson police department was criticized for its use of militarized equipment.

In the eyes of some experts, Ferguson was simply the culmination of years of police militarization. According to Dr. Peter Kraska, Ferguson was the “flashpoint” of a larger issue.

“All of that angst has been building over a 25-year period,” Kraska said. “Ferguson was just the tipping point that made people say, ‘You know, enough is enough.’ This stuff has been building for a long time.”

Kraska is a professor and the chair of graduate studies at the Eastern Kentucky University School of Justice Studies. He’s spent years studied trends in police brutality and how military equipment affects the community. Kraska is currently serving on a White House commission that is reevaluating the effectiveness of the 1033 Program.

The general mindset of police departments has shifted in the past decade, according to Kraska.

“We had a massive community policing reform effort in the 1990s and through the 2000s that really started to make a difference in policing, but there’s been a backlash effect to it,” Kraska said. “What we’ve seen now is a trend towards militarization instead of democratization.”

Kraska said that he believes that the 1033 Program sends the wrong message to community police departments.

“It just adds to an increasing mindset in the policing world, which says that the military model and the military approach is the best way to handle our domestic and social problems,” Kraska said. “It sends those local community police departments a message that, ‘You are waging a war on crime and drugs. And in fact, it’s such a serious war that we’re willing to give you these war-like materials.’”

Though there are some instances where 1033 equipment is helpful, Kraska said he believes it’s not necessary in many cases—especially considering that a fair amount of the equipment goes to police forces in small communities who don’t necessarily need it.

“To argue that armored personnel carriers or bayonets or M16s are something that a police department needs on a regular basis really stretches credibility,” Kraska said. “The truth of the matter is they’re very unlikely to encounter, and probably have never encountered, a situation where something like that might be appropriate.”

But, Kraska said, the use of the equipment has prevailed, partly due to what he calls “what if” scenarios. He gave an example that he witnessed while testifying before the Kentucky State Legislature.

“There was a chief of police testifying next to me. He was arguing that his police need the military bayonets in the trunk of their car in case they have to cut a baby out of a car seat from an auto accident.” Kraska said. “Amazingly, most of the legislators were nodding their heads as if that sounded reasonable. If people are going to see a cop running across the street holding a double-sided 12-inch-long bayonet to cut a baby out of a car seat as reasonable, then how are we ever going to get them to shut down the 1033 Program?”

Kraska said he believes one of the biggest issues with the 1033 Program is the lack of regulation, which is something the White House commission is trying to fix.

“One of the big issues that Senator [Claire] McCaskill has covered, and I’ve known for the last 20 years, is that there is very little oversight,” Kraska said. “When the federal government has been asked who specifically got what, and why they got it, and how they’ve used it, they can rarely answer those kinds of questions.”

Some legislators are working to halt the 1033 Program altogether, while others are more focused on providing training and oversight to police departments who receive equipment.

Despite the reactions to the Ferguson protests and the work of the White House commission, Kraska isn’t confident that the 1033 Program will ever change dramatically.

“The police are a powerful political body, and they’ve demonstrated it,” Kraska said. “When this all started in Ferguson, I naively thought there was a chance that Obama or Chuck Hagel would step in and put a stop to 1033. But the police lobby kicked in.”

Of course, Kraska said, the paradigm could shift on a local level, due to pressure from community members. But national change could take a while, he said.

“Obama and his administration actually want to put some restrictions on the 1033 program, so he’s asking our body of people to come up with recommendations,” Kraska said. “The trendline is not going to reverse, in my opinion. But that doesn’t mean that in individual circumstances and communities, things can’t change.”

The Central Marin police have taken steps toward community-oriented policing. McKenna said that many of the officers have begun to use “less-lethal” shotguns, which shoot a “bean bag” instead of a bullet.

“It’s a shotgun shell but it has a little beanbag that’s inside of that, so if you shoot it basically shoots a beanbag at somebody,” McKenna said. “It hurts, but it would also knock somebody down. It’s designed to stop people, so it gives us more options.”

Kraska said that a less-militarized policing model could improve relations between police and their communities.

“It’s just a more democratic way of doing policing—it’s a way of building trust in the community,” Kraska said. “It’s a way of officers communicating directly with community members as opposed to driving down the street in an armored personnel carrier.”