If you’ve read Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” about eating babies or watched The Daily Show make fun of Marin mothers for not vaccinating their children, you’ve seen the impact that satire can have.

Satire has been a highly valued part of our society for centuries, causing delight and laughter at times, while also sometimes provoking outrage and controversy. The National Lampoon, a satirical magazine that ran from 1970 through 1988, is a well-known example of this controversy, featuring covers such as a dog with a gun to its head captioned, “If you don’t buy this magazine, we’ll kill this dog.”

Co-founder of the National Lampoon Henry Beard once described the magazine’s approach: “There was this big door that said, ‘Thou shalt not.’ We touched it, and it fell off its hinges.” Nowadays people aren’t just touching the door; they’re ripping it off its hinges and stepping on it. Why? Because they can.

But are a few humorous comments and points really worth the repercussions? Writers must consider the purpose of satire: Is there a beneficial message being conveyed and will it be informative to society? If not, maybe they should rethink whether or not to publish it.

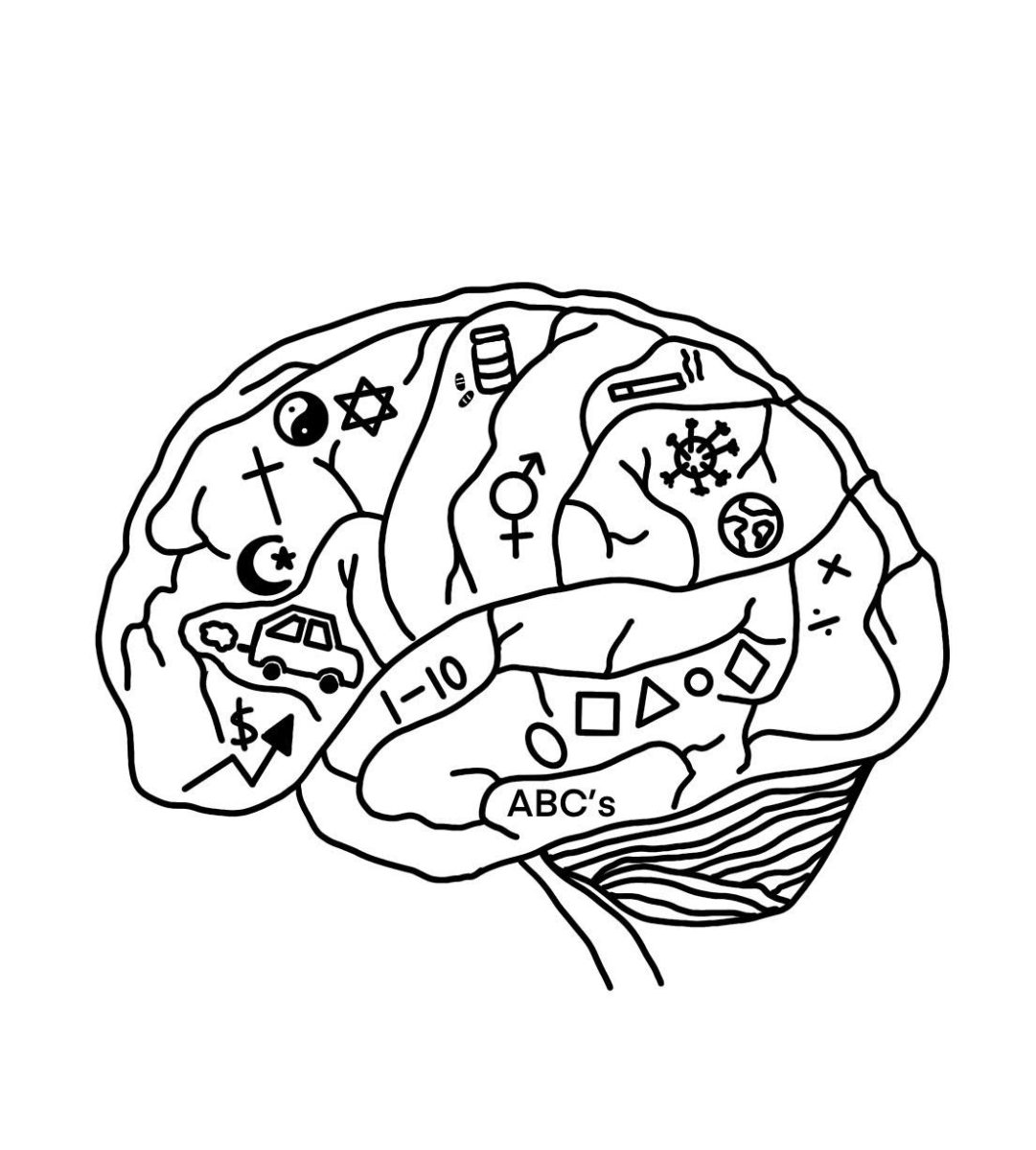

The primary purpose of satire may appear to be humor. However, satire actually has a more important objective than just arousing a few giggles. Satire is the mockery of things in our lives and society that we want to change. It is supposed to give people a new perspective on these issues and provoke change. If it fails to meet this criteria, then it isn’t really satire, but just plain comedy.

Satire is supposed to reveal corruption and unveil unjust acts, often in a witty and amusing way. Digging up the dirt on sensitive and important topics can have its risks, some of which are worth taking, while others may cross the line.

There comes a point where publishing something can do more harm than good.

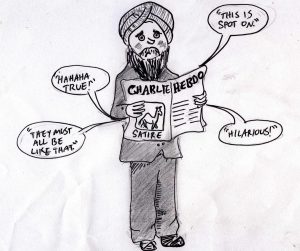

Charlie Hebdo, a French satirical magazine known for their provocative religious and political cartoons, was recently the target of a shooting involving Islamic extremists in which 12 lives were lost. The shooting was the tragic outcome of cartoons depicting Muhammad which the extremists found blasphemous.

While there is no justification for the shooting, it is clear to see why some Islamists were deeply offended by such cartoons. Unless there is a valuable message being conveyed or an issue being addressed, mocking someone’s faith is demeaning and unfair to those on the receiving end.

Another important factor to consider in satire is the audience. We live in such times where the world is our audience with the media and the internet. Because part of satire is the mockery of a person or idea, someone will most likely always be offended, but once again, this is the risk we must take. But how do we know what is okay and what’s taking it to far?

For instance, Sony’s recent movie, The Interview, is a story of two reporters invited to North Korea to interview the country’s dictator, which ends up turning into an assassination. This movie was a failure of satire because not only did it channel an immature message of killing a current leader, but it put the United States at risk of North Korean terrorist plots. Either way, when making a movie on North Korea, risks are being taken. Rather than taking risks for “stoner” jokes, writers should take them to make a change in society and to uncover unjustified practices which are still in practice this very moment.

With this all in mind, next time people come to the door labeled, “Thou shalt not pass,” consider whether it’s worth ripping it off its hinges. If its not, just shake the conventional door because you never know what lies on the other side.

To read the opposing view, click here: https://redwoodbark.org/2015/02/charlie-hebdo-offensive-or-not-its-their-right-to-print/