Discomfort. Resentment. Anger.

Junior “Lindsay” sees thin girls around her and wants to look like them. “Candice,” a junior, wishes she was born with the petite bone structure of her extended family and resents her parents for being “bigger boned.” Lindsay is swamped by pictures of perfect celebrities and uses them as “place markers” for what she wants to look like. Candice feels out of place and “uncomfortable,” being taller and bigger than all her other friends, and wants to change her looks. Both begin to drop weight dramatically, and as Lindsay says, she is “scared of getting help.”

Today, Lindsay and Candice are still recovering from their eating disorders.

Forty to 60 percent of girls aged six to 12 are concerned about their weight or becoming fat, according to the National Eating Disorder Association (NEDA). The National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders (ANAD) stated that 47 percent of girls in fifth to twelfth grade want to lose weight because of the media.

Lindsay developed anorexia in middle school. She had already been seeing a psychiatrist for clinical depression since the age of eight––she was diagnosed with anorexia in seventh grade, and bulimia in eighth.

“A lot of it was pressure from society, but I also compared myself to other people,” she said. “I started noticing other peoples’ physique and I’d want or not want what they had, and I started using people as place markers for where I wanted to get myself.”

Ten million women suffer from anorexia or bulimia in the United States, according to NEDA, yet only 10 percent of those get professional help. A December Bark survey revealed that 32.5 percent of females at Redwood have considered themselves to have an eating disorder at some point and 7.5 percent have been medically diagnosed.

Lindsay received counseling from her psychiatrist, but never went to an eating disorder specialist to be treated.

“It was really hard at first to accept my physique and what I look like, but starting with high school, I surrounded myself with good people who made me feel accepted,” she said. “They pushed me, they had me eat good meals and made sure they stayed in my stomach.”

Lindsay said that recognizing if a person has an eating disorder is difficult and often goes unrecognized. She said that people in Marin often seem “oblivious” to the fact that some people may have an eating disorder.

“Everyone, especially at this time, in this area, are pretty focused on themselves, and most of it goes unrecognized,” she said.

Lindsay added that she has met people who assume that eating disorders are a way of getting attention––she said they should realize that there’s always a deeper reason.

Compared to the 10 million women suffering from eating disorders, 1 million men have anorexia or bulimia, according to NEDA.

“I think they’re far less likely to ask for help, and because the disease is associated with women, they might be afraid of asking for help––like it makes them seem more feminine,” said psychotherapist Elizabeth Scott.

Scott is the co-founder of The Body Positive, a nonprofit that treats people with eating disorders and helps people develop positive body images.

Junior “Edward” was on a strict diet during his entire sophomore year because he was a lightweight rower.

In order to stay under the 150 pound weight limit for races, Edward worked with a dietician. He said that he didn’t have an eating disorder, but was conscious of what he ate.

“Everything I ate, I felt worried that it would affect my weight,” Edward said.

Edward said he never developed an eating disorder because of his close work with his dietician. He is among the more fortunate athletes. According to ANAD, athletes who participate in sports that are classified by weight or aesthetics are at a higher risk of eating disorders than athletes whose sports don’t impose weight standards.

The Bark survey showed that 5 percent of males at Redwood believe themselves to have an eating disorder. 3.8 percent of males have been medically diagnosed with an eating disorder.

Edward believes that fewer boys may have eating disorders because they don’t worry about their weight as much, though he reiterates that this doesn’t mean they aren’t self-conscious.

“I feel like guys don’t worry as much, like when they step on a scale, they aren’t worried about their weight, but they care about how they look,” he said.

Boys are just as influenced by magazine advertisements as girls, Edward said.

“We see guys in advertisements, and they’re always just very fit and don’t have a lot of fat and have a lot of muscle,” he said. “It could cause [boys] to be insecure.”

The Bark survey showed that 32.5 percent of girls considered themselves to have had an eating disorder at some point, compared to five percent of boys. 3.8 percent have been medically diagnosed.

Candice developed bulimia as a byproduct of the end of her sports season. Upon going home after school, she would be sedentary, which caused her to be less fit than before.

“When I didn’t have sports, I would go right home after school, eat a full meal instead of just a snack, and watch TV and sit on the couch,” she said.

Candice’s bulimic patterns began in the seventh grade, but it was never formally diagnosed like Lindsay’s anorexia was.

Her patterns began after getting food poisoning. Once recovered, she realized that throwing up had caused her to lose weight, so she began to force herself to throw up.

“I was so uncomfortable, and had given up on myself, not trying to work harder to become something I was proud of.” Candice said.

At the end of her sophomore year, Candice began to recover solely with the help of her boyfriend. She never told her friends about her eating disorder.

“I don’t want my friends to think differently about me. It’s not something I’m proud of,” Candice said.

She added that she kept it from her parents because she feared that the truth would tear her family apart.

“I didn’t want to tell my parents and have my parents be disappointed in me. I think they’d be disappointed that I didn’t say anything about it, that it got to the extent that it did, and that I never told them or they never noticed.”

Where to get help:

If you or anyone you know is suffering from an eating disorder, the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders can provide help at anadhelp@anad.org as well as on a helpline, which can be reached at 630-577.1330. The National Eating Disorders Association also provides help at 1-800-931-2237 and has support groups which can be joined at supportgroups@myneda.org. The Body Positive also offers help at 510- 528-0101 or on

http://thebodypositive.org/ and their offices are located in San Rafael.

The Redwood counseling office can also help anyone suffering from a disorder, and can be reached at 415-945-3626.

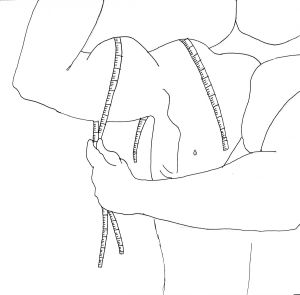

Different body types:

The concept of body types, called somatotypes, was coined by psychologist William H. Sheldon in the 1940s, and have since been referred to by doctors, nutritionists and other experts. In Sheldon’s classifications, three basic body types exist: ectomorph, endomorph, and mesomorph. Given which basic category a person falls into, they will have a different body build and metabolic rate. People with an ectomorph body type have long slender limbs, a thin bone structure, and a fast metabolism, making it hard for them to gain fat or muscle. Those with an endomorph body type are more round, with shorter limbs and less developed muscles. This body type makes it hard to gain muscle and easy to store fat. The last basic body type a person can have is a mesomorph. They fall in between ectomorphs and endomorphs, and thus share characteristics of both. While they have a medium bone structure, they also have a low body fat percentage, burning fat while gaining muscle faster than people in the other categories.