Senior Lucretia King was sleeping about 2 1/2 hours a night in seventh grade before she finally went to the doctor and was diagnosed with insomnia.

“I would stay up really, really, really late and couldn’t fall asleep,” King said. “I would try to read a book or watch TV until I could fall asleep and then I’d get caught up with that, and then I’d never fall asleep. It was very difficult.”

Insomnia is characterized by the persistent inability to fall asleep or stay asleep, or the persistent waking up at a time earlier than desired, according to Britney Blair, Psy.D., CBSM, an insomnia expert at the Stanford University School of Medicine. Blair specializes in cognitive behavioral therapy, one form of treatment for insomnia.

When King’s insomnia began, she was unable to fall asleep until 5 a.m. and then had to wake up at 7:30 to make it to school by 8:30.

“I was really tired, and I’d run out of energy really quickly,” King said. “It was really bad because it affected my grades and being friendly with people, and then I had sports, so it was taking a toll on my body and my brain.”

King said that her grades used to hover in the A and B range. She said that since the onset of her insomnia, however, she can only manage Bs and Cs with the occasional A.

“It’s very difficult [to stay focused in class],” King said. “I’ll start thinking about things because I can’t focus on the teachers. If we watch a movie, my eyes will start to droop and I have to wake up. But I can’t wake up, so I have to get up and go to the bathroom or go somewhere to wake myself up. And then when I really need to sleep, I can’t.”

After living with insomnia for many years, King has figured out ways to fall asleep more easily. Today, she manages to squeeze in four or five hours of sleep a night, hitting the sack at about 2 a.m. or 3 a.m. most nights, though it can be closer to 4 a.m. on rougher nights.

“I try to wear myself out throughout the day, go 110 percent throughout drama or school or whatever I have,” King said. “When I’ve worked my body physically and mentally, it’ll make me fall asleep more easily.”

The ability to focus in school is not the only thing affected by insomnia. King noticed that when her sleep quality tanked, her mood did, too.

“It makes me crankier than I should be at this age, and more irritated. I also don’t have a big tolerance with people when they’re annoying, which is a problem,” she said.

King also finds that she has a hard time remembering names and memorizing material for school, which she attributes to her insomnia.

“I have bad short term memory, which I believe comes from not sleeping,” she said.

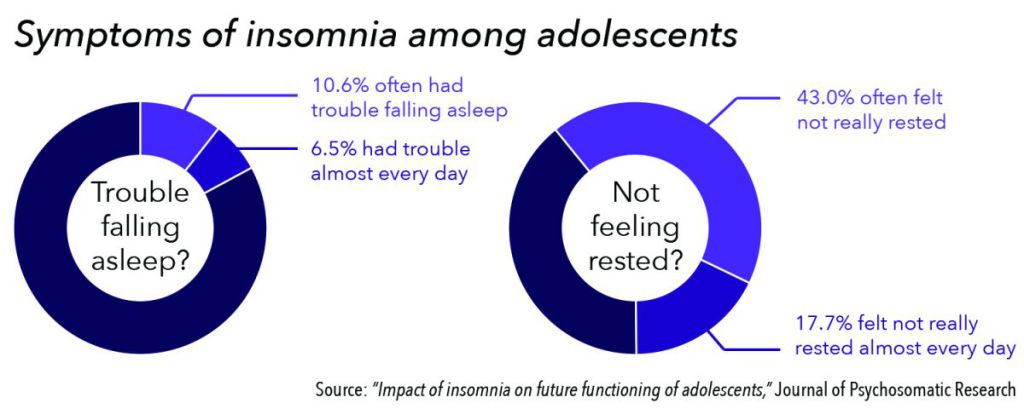

Insomnia affects only a small fraction of the adolescent population, but significantly debilitates those who have it. While King’s sleep challenges may seem characteristic of any other teen who can’t get enough sleep, what distinguishes her from the average sleep-deprived teen is that she can never catch up on the weekends.

“For folks who have chronic insomnia, it’s almost as if the brain has forgotten how to sleep,” Blair said. “It’s really difficult. It makes everything much harder. It’s harder to think straight, and it’s harder to do things physically because your body’s not working as well as it would after a good night’s sleep.”

Unlike King, junior Marguerite Renner is a self-diagnosed insomniac. She said that her doctors simply tell her to go to bed earlier when she tells them she can’t sleep. It often takes her two hours to fall asleep at night, putting the clock at 12 or 1 a.m. when she finally falls asleep.

“I feel like I start waking up around the end of the day, so I kind of get used to being awake right when I’m supposed to be going to bed,” Renner said.

According to Blair, this inability to fall asleep is the result of a biological clock shift called delayed sleep phase syndrome (DSPS), and it affects about 20 percent of teens. For teens with DSPS, getting in bed at 11 p.m. would be like a healthy sleeper getting in bed at 7 p.m, Blair said.

“They’ll lie in bed awake for a couple of hours and then try to get to sleep, which doesn’t work, and then they have to get up for school at 6 a.m., which is very painful,” Blair said. “For them, it’s like a usual sleeper getting up at 3 a.m.”

Renner said that she often waits to do her homework until late at night, when she’s more awake, though she tries to turn off her electronics at 9:30 or 10 p.m. since she’s heard that the bright light can affect the ability to fall asleep.

Blair cautioned against doing mind-straining work at night, since the activity can keep the mind preoccupied when trying to fall asleep.

“In those late night hours – from 10 p.m. on – do something that’s really mellow, and make sure that the mind is super calm,” Blair said, adding that reading a magazine or watching reruns of sitcoms can be soothing late night activities.

Why does insomnia start in the first place? The causes are varied, but major stressful life events seem to be the main factor for most.

For Renner, the insomnia started in sixth grade when family issues and worries about friends kept her awake at night. Ever since then, she’s had a hard time falling asleep.

Other causes of insomnia include a break up with a partner, chronic pain, a mental health condition such as depression and anxiety, PTSD, substance use, and side effects from illicit and prescription drugs.

“A lot of people will drink to help them fall asleep, but then it actually disrupts their sleep in the middle of the night,” Blair said. “They’ll smoke pot to get all relaxed and fall asleep, and then that disrupts their sleep in the middle of the night.”

Blair has seen some high school seniors develop insomnia after the hectic college application process. Even after acceptances are announced and the stress is over, seniors whose sleep was disrupted during the process might never return to their original sleep patterns.

“The healthy sleep doesn’t come back,” Blair said. “The person will live with poor sleep indefinitely.”

Insomnia can be compared to a train that’s been derailed, Blair said. If a stressful event throws sleep “off its tracks,” the sleep will never “get back on its tracks” unless it’s treated. Blair noted that she’s seen people whose sleep was disrupted in college and who still can’t sleep soundly in their forties.

To get the sleep back on its tracks, Blair recommends limiting the time in bed to the actual time asleep. Getting in bed before the body is ready to sleep can actually backfire, as the mind will begin to associate being in bed with being awake.

“Your body gets used to laying in bed and stressing out about the sleep and trying for the sleep,” Blair said. “The more you try for sleep, the more you focus on it, the less likely you are to actually get to sleep.”

Adhering to a morning routine is also critical to healthy sleep, Blair said.

“The single most important thing you can do for healthy sleep is get up at the same time every single day, no matter weekday or weekend and no matter whether you’ve slept for 10 hours or six hours,” Blair said. “By getting up at the same time every day, you anchor your biological clock, which helps create a strong sleep system.”

Insomniacs can also see specialists like Blair, who will work with patients to customize treatment.