Sophomore Matthew Moser was one of ten high school students in California invited to present their science fair experiments to scientific professionals at the Exploratorium on May 12.

Moser competed at the Marin County, San Francisco, and California State Science Fairs. After winning first place at the Marin County Science Fair and second place at the San Francisco Science Fair, Moser was chosen by the head of the San Francisco Science Fair to present his project to members of the scientific community at the Exploratorium, including Sarah Bowes, a member of the New York Department of Health.

Moser’s project was on the effect of auranofin on adult and larval mosquitoes–the organisms, or vectors, which carry malaria. Auranofin is a gold complex anti-inflammatory arthritis drug that has been FDA-approved for over 25 years. The goal of Moser’s experiment was to test whether auranofin could kill mosquitoes infected with malaria.

“[Researchers] found that when auranofin is in a culture, it harbors a certain enzyme good for killing certain proteins,” Moser said. “They took a sample of malaria and found that when tested in an auranofin culture, [auranofin] can kill parts of malaria. My project didn’t want to test malaria, rather, it tested the vectors of malaria. So I kind of went one step ahead of the researchers.”

Moser obtained the mosquitoes and mosquito larvae from the Marin-Sonoma Mosquito and Vector Control District. He hatched the mosquito larvae and let them naturally absorb high, medium, or low concentrations of auranofin and sugar water while inside small cups.

Moser found that the high concentration of auranofin killed the most male and female larval mosquitoes in their early stages, while the medium concentration of auranofin killed the most adult female mosquitoes.

“With my and other scientists’ results, it shows that [auranofin] has a dual usage–one for arthritis, and the other as a possible malarial treatment or insecticide,” Moser said.

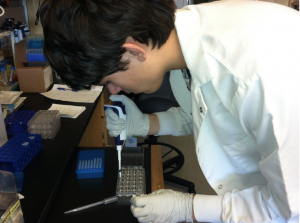

Moser conducted most of his experiment from his mother’s parasitology lab at UCSF, where she and other researchers study parasites and their hosts.

“At my mother’s lab at UCSF, I was given access to the drug, auranofin. I was also able to use a machine called the Worminator, which is the only kind in the world built specifically for UCSF,” Moser said. “It counts how many pixels per second are being displaced under a certain camera. That really helped with my research when trying to find effects of the drug on larval stages, because you can’t count under the naked eye which larvae are alive. You kind of have to wake them up and put them under [the Worminator] which helps a lot.”

Moser’s procedures were also done in part on his very own kitchen counter at home.

“The procedures were very low-scale. I kept most of my mosquitos at home in my kitchen in a small corner, hoping no earthquake came and shook them out, or else infected mosquitoes would be everywhere.”

Moser not only conducted his experiment at home, but found inspiration to fully pursue this project from his parents. “My entire life I have been surrounded by science,” Moser said. “My dad and my mom are both parasitologists and I just love parasite.”

The most tedious, yet the most rewarding part of his experiment was determining the sex of the mosquitos.

“I had to go under a microscope and spend hours trying to figure out which mosquitoes were male and female,” Moser said. “Sometimes you would have mutations with only one eye, a wing, and a small piece of their body. There are a lot of unknowns, unfortunately, but I would say just having to work through everything was really fun.”

Moser hopes to continue research in parasitology. He is especially interested in finding the unknown active ingredient of auranofin. In addition, he wants to create new devices for mosquito traps incorporating his new findings.