The racers emerge from the trail, splattered in dirt and blood. Their faces express the exhaustion of the past 7.4 miles, but miraculously, their bodies continue to pick up speed. Each runner pushes to be the next added to the distinct list of people who can call themselves Dipsea Race finishers.

Sunday, June 8, will mark the 104th running of the historic race. This prominent race has overcome more than a century of challenges and is the second oldest footrace in the United States.

“It’s Marin’s own. It’s something that people throughout the country and even the world associate with Marin,” said Barry Spitz, a Mill Valley runner who has been the Dipsea finish line announcer for the past 32 years.

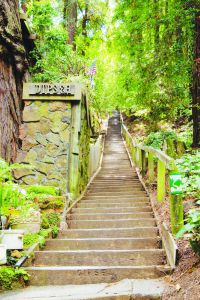

In addition to the camaraderie and local feel, the race is unusual in every sense, complete with time handicaps, legal short-cuts, and 2,200 foot climb over the narrow dirt rails of Mt. Tamalpais.

Julia McInnis, a senior who has run the Dipsea for the past seven years, noted that one unique aspect of the race is the beautiful yet dangerous course.

“The terrain is extremely diverse, there’s roots and it’s really steep and it gets muddy, every year I’ve been on it people have gotten hurt,” McInnis said.

Spitz explained that the high injury rates are partially due to the treacherous course, but are also compounded by the frequent passing that occurs due to the race’s head start handicaps.

Each runner is assigned a start time based on his or her age and gender. These head starts even the playing field so that theoretically anyone can win the race.

Alex Varner, last year’s fastest racer with a race time under 48 minutes, passed more than 400 runners by the time he crossed the finish line.

This staggered start system leads to lots of dangerous passing on small trails as the faster runners catch up with the slower racers who started before them.

One particularly perilous segment of the race is the shortcut known as “Suicide.”

“The first shortcut of the race is called Suicide because it’s insane. I remember the first year I was running with my friend and we actually had guys leap over us because we weren’t going fast enough,” said Leah Cohen, a senior who has run the race five times.

In spite of the injuries, the sense of camaraderie of the Dipsea seems to prevail.

Cohen said she remembers a time when she saw racers stop running to call the the paramedics and help a man who was sitting on the side of the trail dehydrated.

“Some people take it really competitively. It does attract world class runners, but also there’s a whole other part of it that’s just people trying to help each other,” said McInnis.

The injuries are only one of the many challenges the race organizers must face. Another obstacle is simply getting the approval needed to have the race.

Prior to the race, the Dipsea Race Committee is required to get six separate permits from each of the governmental jurisdictions that oversee the different segments of the trail.

Obtaining these permits has created many challenges and caused many changes to the race over the years.

The State and National Parks Services have placed restrictions, including a cap of 1,500 runners, on the race due to the concern of the harsh environmental impact from such a large event.

This participant cap has led to an extremely competitive entrance process, as many more than 1,500 people want to run the race each year.

The first 750 spots are reserved for invitational runners who have qualified in previous years, the next 500 are given out on a first-come, first-serve basis, another 100 are auctioned off to the highest bidder in a silent “bribe” auction, and the final 300 are randomly drawn from a lottery of everyone else who applies.