I just turned 17. In retrospect, I can hardly imagine what six-year old Blake anticipated when he pulled his Magic 8-Ball down from the shelf and mapped out his future in a series of yes or no questions – though I doubt if any of his juvenile longings chronologically exceeded this date.

He must have imagined that he would have become an astronaut at 14, a millionaire at 16, and, at the very least, be penciled in the encyclopedia next to Alligator and have a few grandkids by the ripe old age of 17. Real Blake’s progress has fallen far short of trajectory.

Seventeen is an age of anticlimax – a letdown marked by the imaginary existence of a birthday cake that our parents don’t want to buy anymore, the quaint recognition that the immortalized words of that somber Von Trapp sister now do indeed apply to us as well, and the legal admission to movies deemed inappropriate because the characters talk like…well how we do every day.

I am willing, in fact, to bet money that Lesley Gore wrote her smash hit, “It’s My Party,” on her 17th birthday. So we blow out our woefully fictional candles and sit down to enjoy a meal that no other person can see or taste. But we taste it nonetheless. It tastes bitter.

In many ways (though I’m sure a neuroscientist would cite cerebral development charts to evidence the validity of our discord) turning 17 is the last farewell to childhood, which is strange because I don’t feel any different than I did five years ago. Teenage pragmatists would likely disagree, favoring 18 as this hallowed mark of experience because it is the age at which we leave home, the age at which we can vote. But they’re wrong. At 16, a misguided adolescent can get caught for shoplifting and be let off with a warning. At 17, he’s a criminal, no longer a product of his environment but an unwanted parasite upon whom the former generation may pin the blame for societal problems.

But no event marks this passage, these changes.

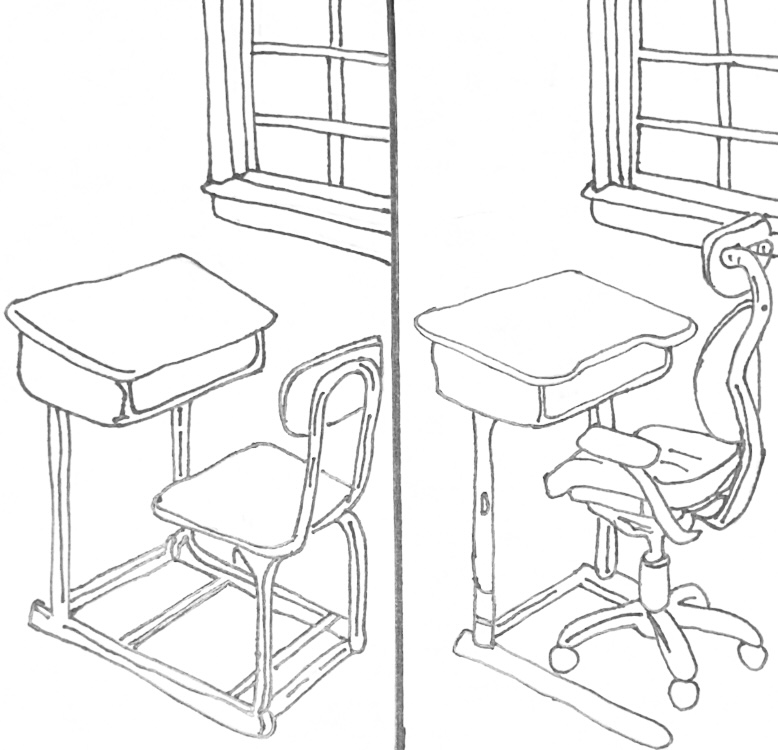

Instead, this change is strictly external, manifested not through self-realization but through the overt, yet kindly gradual mutation of the way outsiders treat us. For instance, when you’re a kid in the checkout line, gnawing at the phantom predilection of the candy bar on the register, and you hand a wrinkled dollar bill to the checker, you savor the ephemeral sojourn into maturity. And if, by chance, you came up a few cents short, even fifty cents short, the checker would usually grumble a little, shrug, and accommodatingly hand you your candy bar with an empathetic simper of nostalgia. When you’re 17, the novelty is gone. When you’re 17, the checker gripes about being handed five George’s in lieu of one Abe, and curtly folds the bills like a bad hand of cards in a poker game before shoving them in the register.

Like a stem cell, we began life with the ability to assume any shape and fill any role – a blank slate, an unshaped hunk of clay on an ambiguous sculptor’s workbench. Aging, it seems, is a process of letting go of indulgency – the humbling epiphany that you were actually right when you told your reflection eight years ago that it’s not possible for so much perfection to fit in one body. We must become comfortable with how commonplace we are, a cathartic detox accompanied by a long and lethal list of side effects including implosion of the ego.

When we are younger and we do something well, the victory, however minute, is lent import by our age – a limited sampling of which we can, given the right achievement, claim to be magistrate of the minute, deity of the day. For instance, if a child scores ten points in a basketball game at age 13, he’s “wet for his age group.”

If a 17 -or 18-year-old scores 10 points in a game, he’s a decent basketball player who has reached an acute apex of mediocrity from which he may only fall until he shakes the dean’s hand, brandishes his diploma, and never steps on a basketball court again. Why? At 18, a high school basketball player realizes that he’s the same age as the real Jabari Parker and that, at this point, he’d have a better chance of actually laughing while watching the “Big Bang Theory” than of being drafted in the NBA.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. If Peter Pan teaches us anything, it is that we must grow up. There are drawbacks to not being considered a child anymore. There are opportunities I left behind in the past. My five-year-old alter ego envisioned a brighter future. But that’s okay.

As Robert Frost wrote, the afternoon knows what the morning never suspected. It’s easy to council the of Blake’s gone by, but although we look back, the clocks keep ticking. 17 then, must not be an age of remorse, but an age of resolution. It’s never too late to carve a better future from the new world ahead.