“Everything that I’d grown up with and taken for granted burned to a crisp. I should have appreciated it more while I was there. It’s just a lesson, a lesson in gratitude, more than anything,” sophomore Cole Sandrich said, who lost his childhood home in the Palisades fire.

Growing up in Marin, wildfires are often seen as a part of the landscape — a distant threat, more of an inconvenience than a personal tragedy. The worst most have faced is ash-dusted yards, smokey skies, canceled sports practices and days spent indoors. We never truly believe it could happen to us. But families in the Palisades of Los Angeles can no longer say the same.

Five days into 2025, California’s second most destructive fire year ignited a scene no one could have anticipated. Over 16,000 homes were reduced to ashes. Thousands were forced to evacuate, some abandoning their cars and escaping on foot, as firefighters from the United States, Mexico and Canada battled relentlessly to control the flames.

The recent fires are a wake-up call, demonstrating that it could have been anyone living in California who lost their homes and their community.

“I personally didn’t think an urban fire like that could ever really affect [any] community like the Pacific Palisades or Marin or Pasadena, but it’s eye-opening. It’s not just a forest fire or big open fields; it’s urban [areas], too. Suburban fires can affect everybody, and we should all be vigilant and have plans,” Sandrich said.

Marin’s history with wildfire safety is commendable, beginning preparations for wildfires in the 1860s, years before any other county in the country. In 1917, the first forest fire-specific fire department was created, and in 2020, the Marin Wildfire Prevention Authority was established, the first known government agency made with the intent to prevent wildfires and mitigate their effects. With the first fire-safe councils, which then prompted more creations of others across the country, Marin is lucky enough to have many resources to help us prepare for potentially destructive fires.

Todd Lando, the wildfire hazard mitigation specialist and battalion chief for the Central Marin Fire Department, is working to learn from the mistakes that took place in the Los Angeles fires and apply them to Marin County.

“We realize that an ounce of prevention is truly worth a pound of cure when it comes to wildfires,” Lando said.

While everyone is in charge of their homes, certain community members, known as Community Leaders and Block Captains, are in charge of specific neighborhoods and streets. Tim Mossteller is the Community Leader of members living on Palm Hill in Larkspur, and has seen the preparation against fire in Marin increase.

“To be real honest, the Los Angeles fires reinforced what we’ve been trying to do for the last five years. Palm Hill has been a firewise community for five years, and we’re trying to ensure people are prepared to evacuate. Los Angeles wasn’t [prepared for the fires] and that just caused chaos. That reinforces the fact that everyone needs to have an evacuation plan and to practice it enough so [it becomes] second nature,” Mossteller said.

In the firefighting world, it’s unusual for fires to run rampant in early months like January, usually the wettest part of the year. Yet, with climate change ever increasing, the impacts are large weather-wise.

“We predicted that the fire season in California would be year-round. And it’s happened. This is all related to climate change. We’re living it.” Lando said.

Fires are costly to control, and the recent disasters point towards a dim future if people do not learn to live with the changing climate that now affects the future of wildfires. Lando emphasized the importance of focusing on oneself and one’s own home when preparing for wildfires.

“We need people to stop worrying in many ways about what their neighbors are doing and focus on their own homes. We’re all in control of whether or not our home burns. I want to give people hope that they can do things to protect their own home,” Lando said.

The first five feet within a home is called “zone zero,” where it is vital to clear anything ignitable from the area, such as dying plants, weeds or debris. Doing this can save residents time and provide additional safety in an emergency evacuation, as 60 to 90 percent of homes that burn in wildfires are due to embers landing within the first five feet of a home.

Preparing a “go-kit” filled with essentials like important documents ensures that people will have what is truly needed to move forward after the devastation. In the frenzy of a quick evacuation, having a pre-practiced plan for every family member, including special cases with the elderly and pets, is critical.

“Pets are often overlooked until it’s too late, and we know of lots of people who have died during wildfires because they couldn’t find their pets [or] weren’t prepared to take their pets,” Lando said. “People will take huge risks to try to save their cat or dog, and with a little bit of preparation in advance, there’s a lot you can do to protect your animals.”

If people refuse to comply with safety officials and evacuate promptly, they put themselves, their families and the broader community at risk by delaying fire control and forcing first responders to attempt rescue later on.

“Once you’re in this panic mode, your thinking ability is reduced, and unless you’ve planned it out well, you run around, and you take too much time getting out of the house. That happened in Los Angeles. People died in their homes in Palisades because they didn’t make it out in time. The key is to leave early,” Mossteller said. There can be many false truths regarding the safety of evacuation during an emergency, but separating fact from fiction is crucial.

“We know that there’s a lot of fear [in people] about being trapped in their cars while they’re evacuating; people are afraid that they’re going to burn up inside their car. That’s just not true. That’s a myth. The car is the safest place for people to evacuate,” Lando said.

As Lando described, nobody has died in their car because they got stuck in a traffic jam. Roads have been backed up, but everybody who has gotten into their car and onto the pavement has survived. While being faced with the conflict of evacuation can be difficult, the most important thing to do during a wildfire is to remain calm.

People never know when a fire is coming, so they must be ready to go in any situation, including in the middle of the night — like what happened during the Santa Rosa Fire in Coffey Park, as Mosteller described.

“I talked to a person who was there. He said he left so fast that he realized he had forgotten his wallet, and so he turned around to get his wallet, and the back end of his house was on fire. He turned around and ran,” Mossteller said.

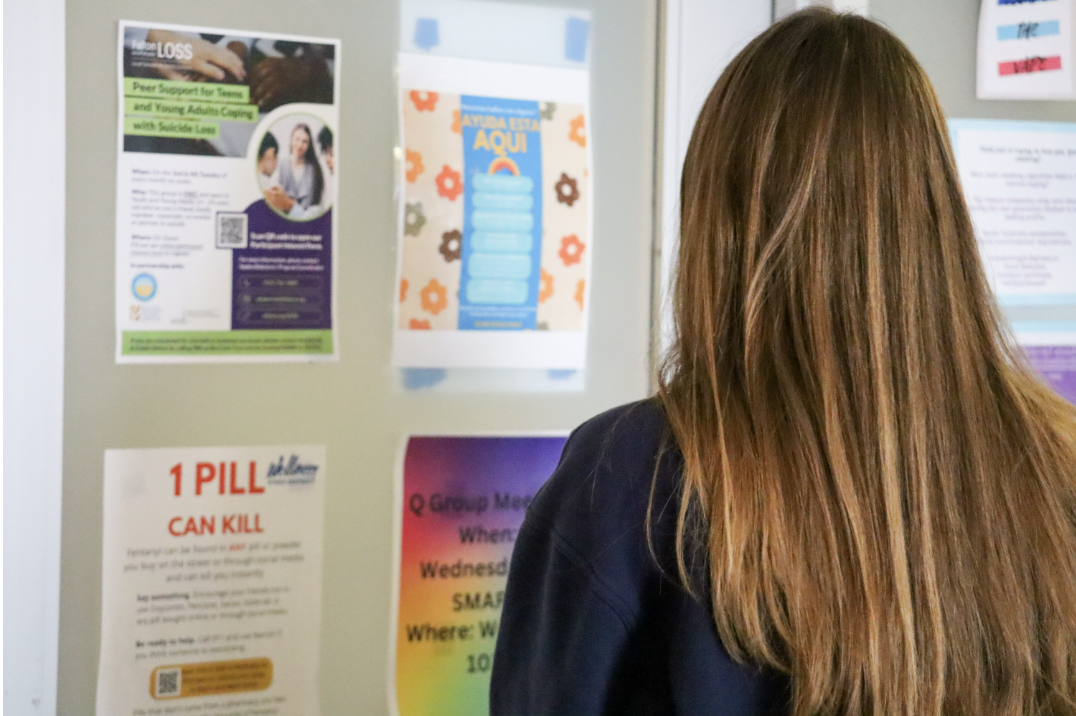

One crucial step anyone can take is to confirm the connection to alert systems. Jessamine Heist, who works with Fire Safe Marin, is signed up for multiple alerts. She finds comfort in knowing she will receive additional safety information in an emergency.

“It’s called No Emergency Management (NEM) and it has the most direct information, especially if you are getting that evacuation order. There’s going to be follow-up information about where you should go to shelter in place and which streets specifically are under evacuation order. There is always going to be more information if you’re under an evacuation order, so it’s important for people to sign up for that and have that awareness,” Heist said.

Above all, Lando wants residents to have hope and optimism even in light of devastating recent events. An overlooked reminder regarding fire safety in Marin is to remain confident.

“You need to be prepared to live with fires. They’re a part of our landscape. You need to build your home so that it will survive a wildfire. You need to prepare your family so your family can survive a wildfire, and when and if we ever get to that point, that’s part of our ethic of living here in Marin and California,” Lando said.

![“What sold me on [creatine] is its impact on brain health. Some studies show it supports mood by regulating how neurotransmitter building blocks are produced. Creatine helps with mood in the same way an [anti-depressant] helps with mood,” Baker said.](https://redwoodbark.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unjAxWLY4AvG7cPOCe5ht0J0AFo68itewOijByLJ-1200x800.jpg)