In the late 1970s, a practice known as volunteer tourism, or voluntourism, rapidly gained popularity. Well-intentioned individuals in developed countries travelled abroad by the thousands to volunteer for short period of time in remote corners of the globe. Today, many organizations now allow individuals unique “once-in-a-lifetime” opportunities to “give back to the world” by hosting chaperoned international experiences.

Despite ostensibly good intentions, voluntourism is rooted in the concept that one person’s impoverishment is another person’s opportunity for adventure and personal growth.

I see this in comments from fellow classmates who have had the opportunity to volunteer abroad such as “it was eye-opening” or “it changed my life forever” make me question who benefits most from such experiences.

An impoverished location or community mostly only benefits while the volunteer is actually there volunteering. The volunteer goes home. The community service stops. Unless there is a long-term plan, it is hard to believe there is much sustainable value for the community.

On the other hand, the teenage volunteer will most likely be profoundly impacted by the experience. For the rest of their lives, they will be able to conveniently pull the story of their worldly adventure out of their pocket to show how “responsible,” “accepting,” and “mature” they are, whether it’s for college applications or just another space to fill on their resume.

Although trips like these can truly inspire teenagers with a passion for equality and philanthropy, there are subtle but clear messages promoting these trips for the wrong reasons. Providing a topic for college essays, building an impressive resume, and offering boasting rights to parents and students alike are not the right motivations for a student to volunteer abroad.

According to a study done by Washington University in Saint Louis, 43 percent of all international volunteers in the U.S. between 2007 and 2012 only volunteered for 1-2 weeks. Considering the amount of resources required to prepare for and travel to a foreign country, two weeks is hardly enough time to make a lasting difference in an impoverished community. It seems unlikely that the motivating factors behind a trip that short are 100% philanthropic.

Unfortunately, many teenagers who volunteer abroad fail to conduct even the most basic research about the country where they intend to volunteer.

Allowing a historically and culturally-ignorant teenager to march into a foreign community expecting they’re going to provide help to its impoverished citizens can reinforce the ideology that as privileged, white Westerners, we inherently know what is best for others throughout the world. As opposed to fostering cultural exchange, volunteers can leave their experience with reinforced negative stereotypes.

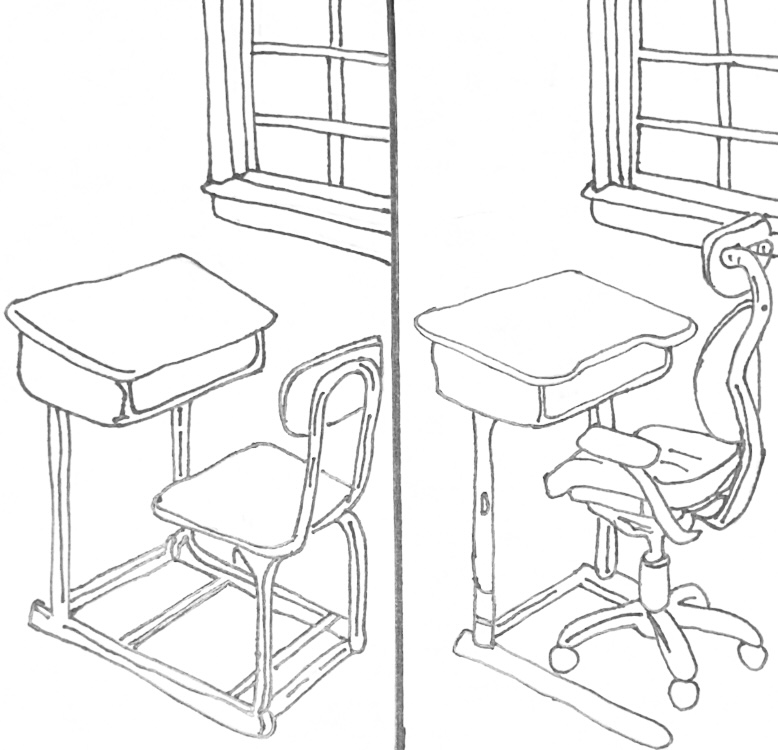

During the summer of my sophomore year, I participated in a unique 6-week immersion volunteer trip to a rural community in Central America where I taught community youth about sanitation and helped construct a local preschool.

I spent months fundraising thousands of dollars prior to the trip, but was only allowed to purchase a few hundred dollars of raw materials for the preschool project in my community.

Even though I felt I made a significant long-term cultural and material impact on the community I visited, I was left wondering how catered the experience was to my needs as opposed to those of the community.

In an attempt to foster an educational, gratifying experience, invaluable time and money that could have gone directly to the community were wasted. It seemed the experience was shaped for my benefit first and my community’s second.

I imagine that in most hosted experiences abroad, the majority of funds will likely pay the overhead and staffing costs for the chaperoning organizations as well for training, medical preparation, packing, and travel expenses.

In the end, most short volunteer trips abroad aren’t going to make a significant, sustainable change on worldwide economic disparities. The real value is the impact these trips can have on teenagers who may be inspired to create change in the world, and that’s a good thing.

It is important to realize, however, that real solutions to the real challenges in impoverished countries can be found in desperately needed policy changes.

Whether you quench your philanthropic thirst by volunteering locally or abroad, just recognize that you may ultimately be getting back a great deal more than you give.

So next time you hear about a three-week “life-changing” trip to Mexico to paint a mural for the great deal of only a couple thousand dollars and truly feel passionate about the international cause, stop and think about it. Unless you are willing to take the time to research the culture and the history of the location you will be visiting and to confirm the long-term sustainable value of the work you will be doing, I have a better idea—donate.