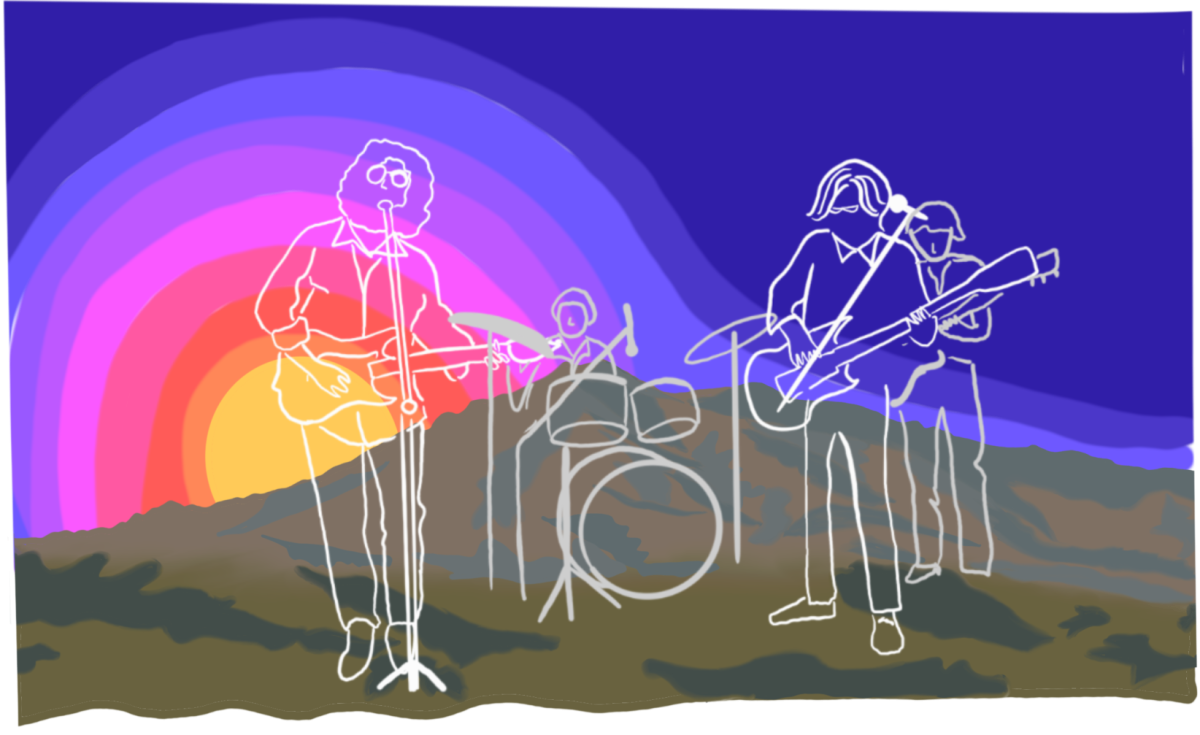

On the weekend of June 10, 1967, the quiet serenity of Mt. Tamalpais broke as 40,000 Bay Area music-lovers shuttled on school buses and the back of Hell’s Angels’ Harleys to the world’s first outdoor rock music festival, the Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Festival. From the Sidney B. Cushing Memorial Amphitheatre, rock n’ roll history was made, inspiring live festivals for years to come. Every major music festival today including Marin’s beloved Bottlerock and Outside Lands can be traced back to this weekend wherein tens of thousands of people bonded over their common appreciation for good music.

It’s fitting that rock music festivals originated in Marin, given the unique ecosystem developing here at the time. The Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Festival was about building a community of music-lovers that would continue to grow through the Summer of Love and years to come. The casual nature of the festival was representative of the community-centered era of music during the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. Talented musicians and regular people lived together without a separation of fame.

In an article by Jason Newman in Rolling Stone magazine about the festival, Jack Casady, lead bassist for Jefferson Airplane said, “When you weren’t on stage, you became part of the audience. You weren’t separating yourself as the ‘glorious performer.’ You were considered part of the community as the audience was considered a big part of your life as a musician. There was a mutual respect. People were really trying to put their best energy into this thing called ‘the community.’”

The move from San Francisco to Marin

The festival coincided with the migration of musicians from San Francisco to Marin County around and after the Summer of Love, including the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Sly and the Family Stone, Carlos Santana and Big Brother and the Holding Company. Phil Lesh, founding bassist of the Grateful Dead, thought the migration to Marin was a natural step as the band moved north in pieces.

“Sixty years ago, [Marin] was kind of like a paradise to us — the landscape especially — with all the trees and streams and mountains. All of us were city kids and it really struck a chord. I remember at one point we came out to visit somebody in Marin and we were driving on Shady Lane in Ross with all the big elms and I said, ‘Oh my god, I’d really like to live here.’ And now I do,” Lesh said.

The Grateful Dead moved to Marin from the Haight in 1968 and promptly settled into Marin’s community of musicians. Lesh said that the casual nature of Marin’s rock n’ roll culture in the early ‘70s impacted his development as a musician.

On Sunday, March 3, 1968, the Grateful Dead rolled in on a flatbed truck to the corner of Haight and Ashbury during a mayor-sponsored street fair and played a free concert, just weeks before they transitioned from the crammed Haight area to the serene landscape of Marin County. (Video courtesy of Don Douglas)

“It seems to me that it’s all one big community and everybody plays with everybody else at one time or another. It’s like a soup. [Musicians] interact constantly on a large scale. Everybody kind of moves around to play gigs. And sometimes they play in a garage, just for fun,” Lesh said. “I think of that as a kind of mentoring because when you play with someone it’s a two-way street. You absorb things from each other. So it’s a kind of natural process with musicians.”

In the case of the Grateful Dead, the move to Marin came after the establishment and success of their band. But some bands were born in Marin and developed from there.

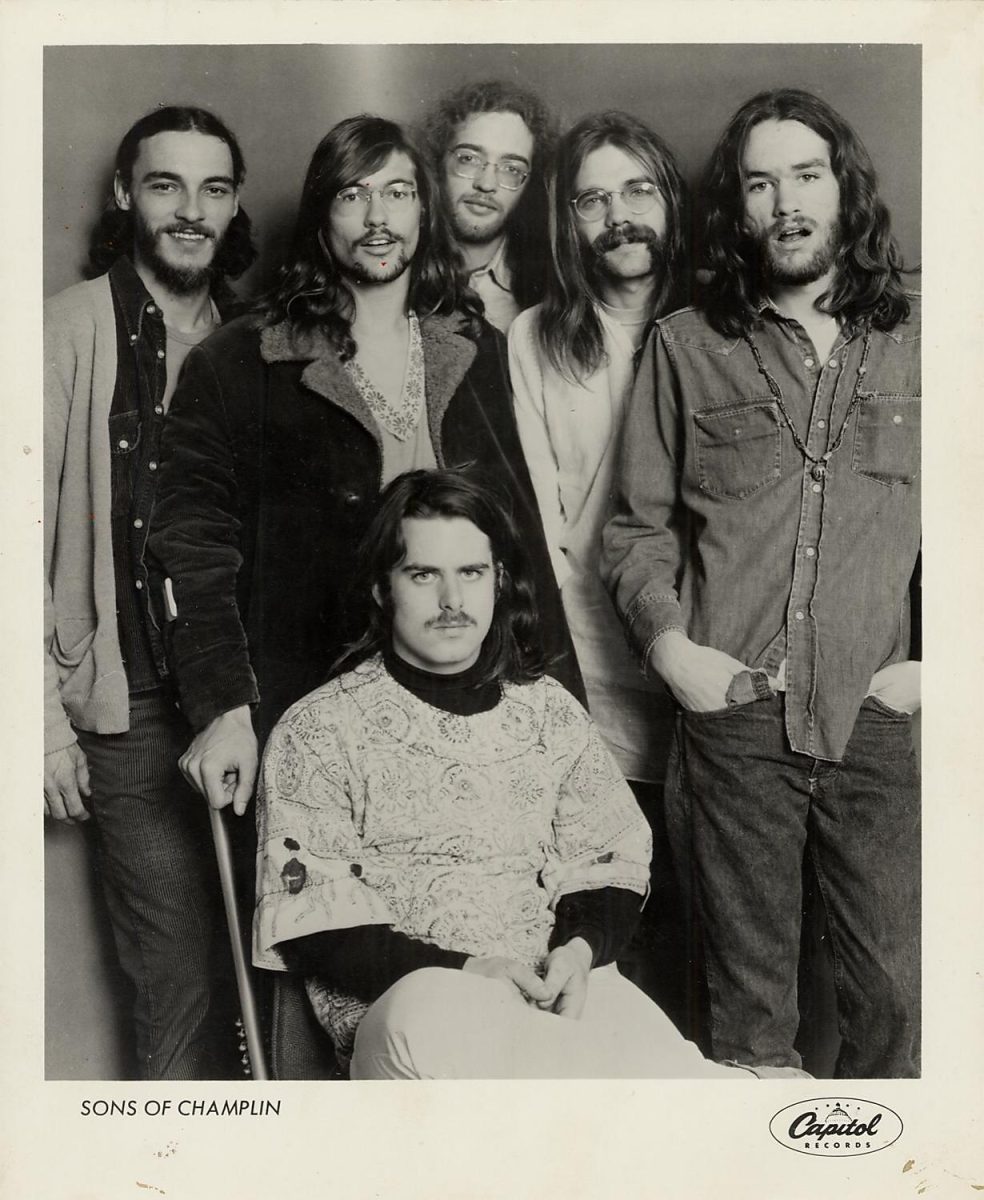

Bill Champlin, a Tamalpais High School alumna, formed a band called the Opposite Six while in high school which developed into Sons of Champlin. His musical journey later evolved into playing for Chicago and receiving several song-writing Grammys.

“There was a certain period of time when something was in the water in the Bay Area. So many great musicians grew like mushrooms after a spring rain. Great musicians everywhere you look. My old sax player in [the band] Chicago referred to [the music venues] as upholstered sewers — jazz clubs and R&B clubs and pop clubs. There were a lot of places to play. There’s not anymore. I drive through San Francisco and I’m pointing at a parking lot [thinking it] used to be a nice club,” Champlin said.

Musicians and Community Together in Marin

In the ‘70s Marin landscape, talent was in the air. And so was a shared appreciation of live music that brought the community together. Jim Perry, Archie Williams class of ‘76, is now a professional visual artist and recently shifted his artistic style from landscape paintings to more abstract poster art, a career change he attributes to coming of age against a radically changing backdrop. He grew up in what he calls “the heyday of the hippie era,” when interacting with talented musicians was part of his everyday life.

“During soccer season, at least a couple times a week, I would be walking towards [the field] and Jerry Garcia would drive by in his silver Porsche. And I would wave to him and he’d wave to me. It’s like ‘Hey, there’s Jerry.’ And Jerry probably thought, ‘Hey, there’s that soccer player.’”

Perry’s parents were traditional and he led a structured home life, but they gave him the independence to explore the wildness of the rapidly shifting music scene.

“In Bolinas, there’s a house at the end of Brighton Avenue, right on the beach, and Jefferson Airplane lived there. I can remember as a kid, probably when I was in my first year of high school, sitting down underneath the cement bulkhead and listening to them practice,” Perry said.

As the connection between musicians and their audiences naturally strengthened, more music venues developed to give them places to play. Even though tickets needed to be bought to get in and free concerts were less common, live music was still greatly accessible to all Marin residents.

“I [once] climbed up a lamppost to check out a show Jerry [Garcia] was playing in a club and the bouncer came out and said, ‘Get the hell off the lamppost.’ There was a big crowd out there and I thought he was gonna kill me and he said, ‘Come with me’ and I followed him around the corner and he goes, ‘Kid, you look like you really ought to be in this show. Come on,’” Perry said.

Music Clubs

“I used to say any place where you play is church. That’s how I feel about [performing]. Give me some musicians and a few people in a bar and we’ll see what we can do,” Lesh said.

One venue that embodied the local feeling of the time was the Lion’s Share, located in San Anselmo, where local bands would hang out and jam. Publisher Diane Sward Rapaport worked in the late ‘60s as an artist’s manager for Bill Graham, an influential promoter of the time, and wrote a description of the Lion’s Share in her blog.

“Nobody minded the bare tables and floors, the wrought iron chairs, a bar that was not 15 feet from the stage, which the owner refused to stop operating when the bands played, so that the ringing of the cash register became an integral part of the music. It was a cold room to play in, except that it was one of the few clubs north of San Francisco in Marin County that hired the hip acts and paid them and that had a sound system and piano,” Rapaport wrote.

Perry spent a lot of time at the Lion’s Share in his teenage years and considers it a huge part of his upbringing.

“One of my fondest memories [at the Lion’s Share] was a band called Cold Blood which was kind of an R&B band. Their lead singer Lydia Pense was this powerhouse; a tiny little lady with a ginormous voice. I was sitting there and the band walked on the stage and [Pense] stepped on my hand with these stiletto boots and it hurt like you cannot believe. I remember she said, ‘Oh hon, I’m so sorry.’ It hurt like crazy. But I didn’t wash my hands for a week,” Perry said.

The Lion’s Share is now an abandoned-looking manufacturing facility and you would never guess its history as such a legendary rock venue. The hundreds of events enjoyed there, including Janis Joplin’s wake in 1970, will be memorialized forever in memories of the many audiences.

“I don’t think any of those venues [from the ‘70s] are going on right now. The Fillmore was taken over by Live Nation, a giant conglomerate corporation. They buy and sell rock venues the way other people buy and sell cases of beer. The minute corporations jump into the ballgame, when a band is making decisions in a corporate boardroom, the decisions start to become a little jaded. I always liked the decisions that were made over a greasy pizza and some beer,” Champlin said.

While the perfect conditions of the ‘70s Marin music scene are long gone and the informal jam sessions of the ‘70s have been replaced by calculated and expensive concerts, it’s not too late to return to “the community” Jack Casady described at the Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Festival 60 years ago. The clues to the history of rock n’ roll music lie everywhere we look. We may not realize the hidden stories in plain sight of venues like the Lion’s Share, but we likely wouldn’t have the rock music of today without them.