For most seniors, their last year of high school is the culmination of their four-year journey, a time to savor their final year. Simultaneously, this time can be tainted by the stress of countless hours spent applying to college and anxiously awaiting acceptance letters. Yet there are always a select handful of student-athletes who do not have to endure this uncertainty as they have, one or two years prior – long before they have finished their academic career – been somewhat promised admission as a recruited athlete. However, only granting admission advantages to athletes while ignoring other talents creates inequality and undermines the principles of fairness in college admissions. In addition, prioritizing athletic ability over academic merit compromises the academic integrity of institutions and, most importantly, neglects underrepresented communities for whom the process was supposedly initially designed.

While colleges eagerly recruit students under academic par for reasons involving sports, we don’t see similar admission routes for students with other skills. Expertise in dance, art, music, computer science, math and journalism are equally impressive as expertise in sports, yet they don’t get the same recognition for the required talent and hard work. Those pursuing art, music, computer sciences and other aptitudes are typically admitted to the relevant department set on a trajectory for their skills. In contrast, athletes get accepted into schools and majors that have little to do with their recruited expertise.

One of the reasons colleges have said that they give an advantage to athletes is to create opportunities for talented and dedicated underprivileged kids and minorities. But overall, most recruited athletes are not marginalized; they are, in fact, privileged. The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) released data showing that out of the Ivy League and New England Small College Athletic Conference (NESCAC), 61 percent of the athletes they recruited were white. Within that, sailing recruitment was 100 percent white. There is also under 2 percent black representation in field hockey, rowing and ice hockey. This poses the question, are the students getting into colleges as recruited athletes really the ones who need a leg up? Or do they get an advantage because they’ve been born into families that can pay for these elite teams and equipment, which is simply unrealistic for most kids?

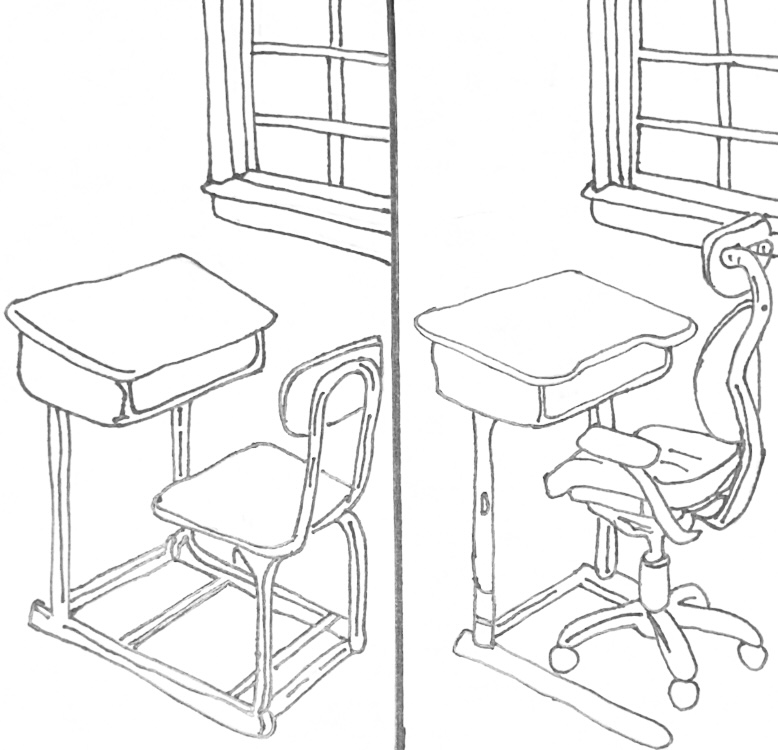

The athletic recruitment admission process also causes a drop in the overall intellectual level of a class, diminishing the scholastic experience for academically qualified students. Ivy League schools developed a system to measure a student-athlete’s academic qualifications called the Academic Index (AI). Many other Division 1 and Division 3 schools have adopted this system or developed a similar one as well. Through the AI, admissions officers combine standardized testing scores and high school Grade Point Averages (GPA) to create a total AI. At Ivy League schools, student-athletes need a minimum AI of 176, but the class average for all other admittees is 220-210. In the Patriot League, student-athletes need a 168 (basketball and football players need a 166) and the NESCAC has yet to disclose their minimum. In fact, the Ivy League’s website for Prospective Athlete Information pushes for the admission of student-athletes even if they may not be of the same academic caliber as other potential students: “Coaches may communicate to the Admissions Office their support for candidates who are athletic recruits.” Thus, the support from a coach is ultimately what pushes the student through the process. We don’t see similar opportunities and treatments for other skills that have worked equally hard.

Knowing this academic gap, The Harvard Crimson surveyed the class of 2027 and found that student-athletes’ SAT scores were a whopping 160 points behind the average student’s. William G. Bowen’s book Reclaiming the Game found that 81 percent of student-athletes graduated in the bottom third of their class at Ivy League schools. Student-athletes dedicate ample time to perfecting their sport which might lead to them not being of the same academic caliber as others. The pressure to live up to the school’s standards that the athlete isn’t suited for can cause mental strain on a developing young adult. The consequences can be grave and are not worth the psychological burden.

There is no doubt that getting recruited is a fantastic opportunity. There are countless stories of how recruitment has changed lives, such as the story of Micheal Oher which became the hit movie The Blind Side. The idea of recruitment encouraged Oher to become a better student, change his mindset and set goals. Yet, without his athletic talents, Oher likely wouldn’t have gotten into the University of Mississippi. Therefore, athletic programs can inspire kids to get their grades up to meet the school’s expectations for athletes, but if a student-athlete has the ability to get their grades up shouldn’t they undergo the same process as all the other candidates?

As the final whistle blows on the debate around colleges providing advantages to their recruited athletes, the evidence points overwhelmingly to the unfairness of the process. Colleges practice systemic bias and inequality to benefit strong athletic teams without considering all students’ well-being or right to the best academic experience. Hopefully, colleges will admit these flaws, reevaluate their system and level the playing field.