How is it that humans living in the same country and contributing to the same economy can have completely opposing perceptions of the world that surrounds us? Today’s national landscape is marked by divides so extreme that Americans’ ability to solve collective concerns has stagnated. And in this stagnation, mistrust in the institutions designed to support and represent Americans has risen. Underneath this division lies a deeper psychological factor: skepticism — our skepticism of the information we receive, our skepticism of the institutions we are a part of and most importantly, our skepticism of each other.

On some level, possessing a skeptical mindset — or expressing doubt toward the claims with which one is presented — is more important now than ever, as news has become driven by profit to emphasize only the most sensationalized information. We have become predisposed to accept much of this information without further question or analysis. Part of the issue is social media. While its accessibility and individually curated content makes it a fan favorite for news coverage amongst teens, it has also resulted in a decline in skepticism when it matters most. According to a 2023 study by Pew Research, 32% of Americans ages 18 to 29 regularly get news from TikTok. However, rarely is this information looked at through a critical lens. According to a March Bark survey, 27% of students never double-check news they see on social media, while 56% of students sometimes double-check this information. Not only is misinformation more accessible through social media, but it is also geared to appeal to our interests and biases. Junior Ella Buske fell victim to this phenomenon, learning about the importance of skepticism on social media as her feed began to cater to her pre-existing beliefs.

“In sixth grade, when I got Instagram, I got really invested in current events and social activism. But as soon as I started following one or two accounts of the social activism that I was interested in, all of my recommendations shared similar voices and it was a spiral of the algorithm only providing me with the kinds of media I was already consuming,” Buske said.

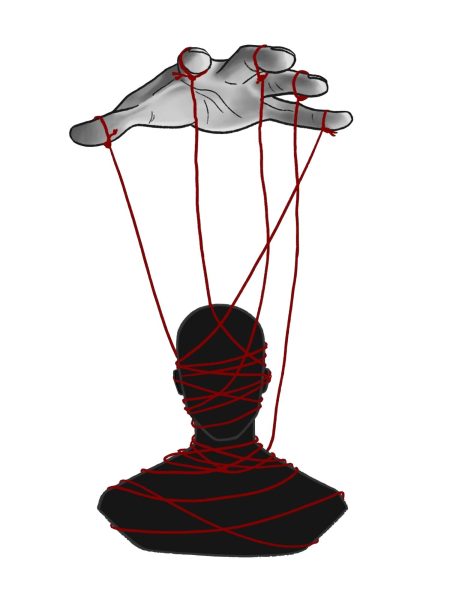

This cycle is perpetuated through the greater engagement that comes from sharing provocative information online. Facebook was one of the first companies to take note of this. From 2016-2019, Facebook’s algorithm prioritized “anger” emoji reactions over “likes,” giving the “anger” reactions five times as much weight as positive reactions. In this, they capitalized on the fact that posts that angered consumers were more likely to generate engagement than neutral posts. For senior Jake Williams, he has observed this spread of misinformation through social media.

“There is such a market with social media to misuse information, get people to watch your [content] and believe what you believe for financial incentive,” Williams said. “The most profitable content is usually the most polarizing content because it catches people’s attention.”

This can lead people to accept information blindly, without any skepticism, as psychology teacher Jonathan Hirsch explained.

“When we hear what we want to hear, or even when we think we’re going to hear what we want to hear, we’re much more likely to accept it without skepticism,” Hirsch said.

However, it is difficult to be skeptical about all the information that is present online. The number of people who get their news from social media may reflect a decline in media literacy, but it also reflects that amid the inundation of polarizing content, it is difficult to discern what exactly is worth looking at through a more critical lens.

Despite its benefits, skepticism can be a double-edged sword. Skepticism can become a force for confirming our existing biases; the instrument once so important for challenging our beliefs can become retooled to confirm them. Often, it is precisely the issues that target our most deeply held beliefs on which it is most crucial that we maintain a level of skepticism, as Hirsch explained.

“If someone has a great amount of political knowledge, they’re more likely to trust what they believe. And if they’ve invested a lot [into being informed], feeling informed is probably a part of their identity. So they are most at risk of feeling like their identity is threatened if their political assumptions are threatened,” Hirsch said.

This concept was particularly prevalent in respect to the so-called “birther” conspiracy theories surrounding former president Barack Obama’s country of birth. According to a 2019 study by the University of Michigan, Republicans with high levels of racial animus and high amounts of political knowledge were the most likely to believe conspiracy theories about the former president’s birthplace.

Today, the issue of defensiveness over information has played in regards to the Israel-Palestine conflict and the greater levels of polarization the recent war has sparked, as Hirsch discussed.

“You get the same kind of thing [with the Israel-Palestine conflict.] Someone who is pro-Israel is not likely to look at Al-Jazeera. They’re not going to look up, ‘Is Israel’s settlement a violation of the UN Human Rights Declaration?’ Someone who’s pro-Palestine isn’t going to look up, ‘Did Hamas terrorize its own citizens to get [elected]?’” Hirsch said.

This media landscape can also perpetuate division, often unintentionally, as we can become trapped in our own beliefs and perceptions of the world, with little care given to the possibility of flaws within our knowledge. Buske elaborated on this sentiment.

“If someone is relying super heavily on one source or one type of source, they are absolutely going to find their internal monologue sounding more and more like that information,” Buske said.

In this, many reject the opinions of others at face value — and the greater the divide, the worse that skepticism becomes, as Hirsch noted.

“The messenger matters as much as the message, and that works both ways. The more I perceive the messenger as like me, or as someone who I want to be, the more likely I am to accept what they say at face value and not be skeptical about [their message],” Hirsch said. “But the opposite is true as well. The more I perceive you as other — that could be on ethnic, racial, gender or national [lines] — the more likely I am to be skeptical… There’s an element of fear that’s at the root of that: the idea that other people’s opinions might threaten my perception, my beliefs and who I believe myself to be.”

Williams discussed how when skepticism is taken to the extreme, it can separate people from the reality of their situation.

“People get so nihilistic about what they see or what they hear that they think, ‘There’s nobody else I can rely on. There’s nobody else I can take any information from. I can only rely on myself and my perspective.’ But that is just using arrogance as a defense mechanism, from possibly getting hurt or detached from your beliefs,” Williams said

It is crucial, then, to be skeptical not to prove our own beliefs as true, but rather to find the truth — regardless of what that truth may be. For Williams, navigating the national landscape through political content means recognizing that all information he sees will contain some degree of bias and that skepticism will not always lead him to the correct conclusion.

by Linnea Koblik