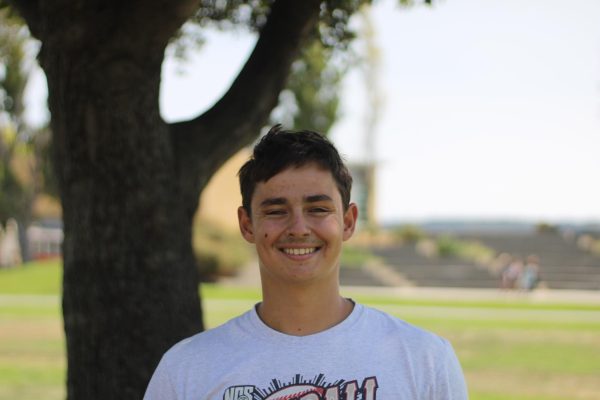

For the first time in my life, I felt timid, afraid and hopeless on the pitcher’s mound. As a sophomore on the boys varsity baseball team, the pressure to succeed, mainly coming from myself, was incredibly high. After a few positive outings, my performance started to decline, and along with it, my ability to perform a basic motor function. Despite having played baseball as long as I could remember, I suddenly could not throw a baseball with any accuracy, tossing balls far above my teammate’s heads and well below their feet. I allowed a simple mechanical flaw to sap all my confidence and remove my focus from the task at hand, instead engulfing myself in the thought of failure.

There’s no simple way to describe this feeling, but experts like to use the white elephant analogy. Imagine being asked not to think about a white elephant. Immediately, the elephant comes front and center to your mind, and the harder you push yourself not to think about it, the clearer the elephant becomes. My white elephant continued for multiple months. I was filled with embarrassment, frustration and self-doubt over my inability to execute such a simple task, one that I had always been able to do. I had come down with a case of the yips, every athlete’s biggest fear.

Dr. Bhrett McCabe, a sports psychologist and consultant for the University of Alabama athletics, has decades of clinical experience with patients who have had the yips. He believes that they begin randomly and that fear and anxiety heighten and continue the problem.

“The yips are a sudden surge of adrenaline or anxiety that starts completely out of the blue [for an athlete]. But it finds a gap in our systems and processes, and then the fear of embarrassment, the fear of it happening, keeps it going, to the point where the athlete cannot complete a simple task,” McCabe said.

Simply avoiding the issue or trying to hide it is a common response in athletes dealing with this unparalleled experience. However, avoidance is the worst way to combat the yips, often only making them worse.

“The harder you try to avoid [the yips], the worse it becomes. By avoiding it, you develop motor patterns that are actually causing and reinforcing the yips,” McCabe said.

Dr. Lazaro Gutierrez, a former mental skills coordinator for the Boston Red Sox and current pitching coach for the University of Miami baseball team, believes that directly addressing the issue before it worsens is the most effective solution.

“How I’ve experienced success with these players who’ve struggled with [the yips] is not to let it grow, not letting it fester, not looking away and praying to God it goes away,” Gutierrez said.

Curing the yips can be a tedious and frustrating process, but Gutierrez has found that creating a protocol and blueprint for recovery is the most advantageous plan.

“There’s a program that I put in place, focusing on using verbalization techniques to take the focus away from the throw. It’s really important to have some type of protocol or drill package that allows these guys to build up confidence,” Gutierrez said.

On the other hand, well-renowned Bay Area pitching coach Jeff Pick utilizes an approach without such specific boundaries or planning and instead tailors his recovery efforts to the individual player.

“Most of the drills I use completely depend on the player. I assess the situation and improvise a drill or activity on the fly. Most of it is trying to get [the athlete] to not think about the same thing they used to think about,” Pick said.

Gutierrez spent five years studying the yips before publishing his findings in 2023. He believes that the overreliance on mechanical cues, such as “keep your arm up” or “extend your left leg,” has led to a sharp increase in the number of yips cases. His studies found that when in a stressful situation, such as a high-intensity moment in a game, directing one’s focus on performing the specific movement instead of focusing on the task at hand can cause the yips.

While they are most well known for occurring in baseball, the yips also appear in other sports. In the 2022 National Football League postseason, Brett Maher missed four extra-point attempts despite previously making them 94.3 percent of the time; this fluke was later attributed to the yips. They show up in golf, too, as a study from the Mayo Clinic cites that almost half of all serious golfers have experienced the yips while putting. Perhaps the most notorious case came from Simone Biles when she dropped out of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics with the ‘twisties’, the gymnastics term coined for the yips.

“[The yips] can show up in anything with an initiation, where the athlete creates the start of a motor movement,” McCabe said.

While most yips cases stem purely from mental inefficiencies, many cases stem from physical injury. The most common is Thoracic Outlet Syndrome, a disorder that compresses nerves and blood vessels between the neck and ribs. This often leads to a partial or complete loss of feeling in the hand or arm, completely ruining an athlete’s proprioception – the ability to perceive the location of our movement in space. Current Major League Baseball pitcher Daniel Bard is a prime example; he experienced tingling in his right hand from compressed nerves in his shoulder, leading him to lose all feel for throwing a baseball.

While there is still large uncertainty surrounding the specific causes of the yips, new studies such as those by Dr. Gutierrez can give a much more educated perspective on the topic and help those struggling. In the age of the mental health crisis, it’s crucial for athletes to maintain focus on the competition and the task instead of being overly robotic or mechanical.