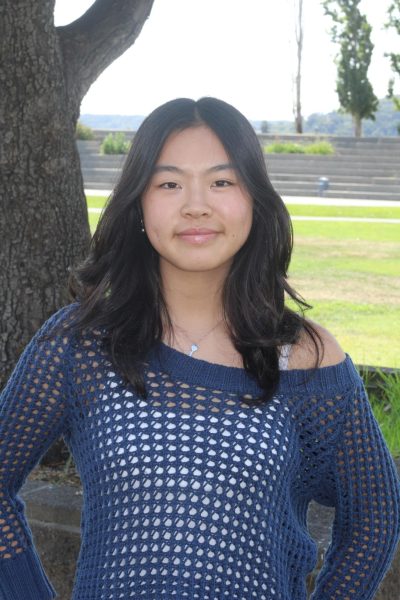

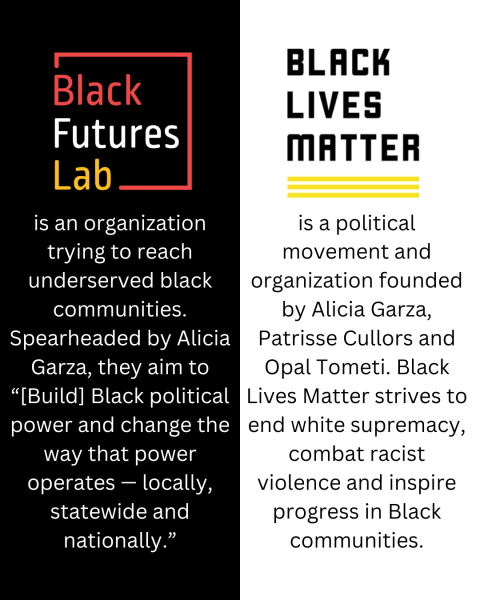

“We want to see a world where Black lives matter for us — to get to a world where all of our humanity is respected,” Alicia Garza said, a Redwood alumna from the class of 1998. Garza, who is also the principal of the Black Futures Lab and a co-founder of Black Lives Matter, has spoken out about many essential topics including voting, social justice and power distribution in today’s government.

Garza began her advocacy with the University of California (UC) Student Association, a group that voices the opinions of UC students, and since then, she has worked hard to become a global change maker

, running multiple organizations while building an online following by speaking her truth.

While Garza is the one who coined the “Black Lives Matter” hashtag after the murder of Trayvon Martin, she does not view the movement wholly as her creation. Rather, she sees the movement as a cumulative effort of resistance against systematic racial disparities, mass incarceration, police brutality and over-criminalization towards people of color in America. The “Black Lives Matter” hashtag has appeared in 44 million tweets since the beginning of the movement in 2013, according to the Pew Research Center.

In addition to advocating for Black Americans, Garza also supports progress concerning women’s equality, the LGBTQ+ community and American immigrants.

Garza’s work for social justice causes has been recognized for her dedication towards change with numerous awards, including the Sydney Peace Prize, the Glamour’s Women of the Year Award, the Community Change Agent at the Black Girls Rock Awards and others.

In the past year, Garza has turned her attention toward voter education and accessibility. With her organization, Black Future Labs, she spoke to over 200,000 under-represented members of the Black community in 2023 alone. She reached out to predominantly Black communities in deep southern states previously untouched by other voter registration programs to increase voter turnout.

In addition, Garza and Black Future Labs work to create communities and change how local, state and national power operates in underserved areas.

“[By] bringing people together to reimagine what society can look like, what government can look like, what our communities can look like, we can then work together to make [social justice] a [reality] for the betterment of all humanity,” Garza said.

Garza emphasizes the significant impact government policies have on the lives of Americans and explains that their power lies in establishing rules and changing them.

“Power can be corrupt, but it doesn’t have to be. Each of us can make an impact on how power operates,” Garza said.

In 2014, to protest police accountability, Garza chained herself to the West Oakland Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) train. She used her power to make a statement and promote action following the court case where a police officer, Darren Wilson, was acquitted after shooting and killing an unarmed teenager, Michael Brown.

Garza empowers people worldwide to speak out against racial injustice in Black communities and to promote change. She explains that this change starts with the people, but is enforced by laws and regulations that shape our country. Garza highlights the importance of participating in the democratic process through electing representative legislators. Deciding who to vote for can be challenging, especially if neither candidate completely aligns with an individual’s values. She emphasizes the importance of selecting the candidate that has the greatest potential to create changes that align with your views.

Garza argues that you don’t need to be an activist to create change, instead voting can be one of the most impactful actions in fighting social injustices. The candidates don’t have to match your ideals completely, but rather vote for what is in your best interest.

Garza also challenges traditional ideas regarding culture and race, commenting on how neither white people nor Black people have a culture, which is an alternative view that presents the idea of Black and white cultures as social constructs invented by white oppressors.

“Whiteness is not a culture. Whiteness is a category that was designed to set people apart from others and give them a rationale. All types of cultures were clumped into whiteness: Irish people, French, English, Scottish and Germans. Black is not a culture; it’s a diaspora that was then used to describe why some people belonged and some didn’t,” Garza said.

By challenging traditional notions of Black culture, Garza redefines the connection between culture and race. The statement, “There isn’t Black culture,” reflects how society views Black people with a different lens in comparison to white people and sets them into a different group based on skin color.

Garza explains that white culture is seen as the more “normal” culture in America and therefore does not require a sub-category that defines it. In contrast, “Black culture” has been established to characterize Black Americans as something different and an embodiment of their own separate culture.

Garza emphasizes that these notions were fabricated to divide people based on “their hue” of skin color and that terms such as “black,” “white” and “brown” do not accurately describe any one culture. Although the gap looks impossible to close, Garza recognizes that society has to start somewhere.

“One of my mentors used to say to me, that change is not just about the place where we’re trying to go,” Garza said. “Change is also about charting the path from where we are.”