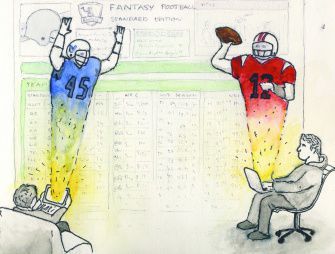

This September, all over America, a record number of devout fans convened to celebrate a sacred ritual: the fantasy football draft.

About 33.5 million Americans — organized into respective leagues of friends, co-workers and distant relations — registered online this year to play fantasy football during the 2013-2014 season.

Conceived in 1961, fantasy football was gradually thrust into the public eye culminating in 1997 when CBS created the first commercial league. Initially the brainchild of a small cult of fanatics, 13 percent of Americans and nearly 20 percent of men now play the game which shoves each player into the shoes of a general manager in the National Football League by allowing them to draft and manage a team comprised of professional athletes.

Each week, a manager’s team is matched up against an opposing squad, the success of which is determined by the statistics accumulated by a real life player during a game. For instance, if a professional running back rushes for 100 yards and a touchdown, his virtual counterpart will contribute 16 points, using standard scoring, to all owning managers. The team that wins a match-up is that which has the most points when the week’s NFL games conclude.

Leagues are generally comprised of eight to 14 people, each of which wagers a predetermined sum of money for entry. At the end of the season, the league champion claims the majority, if not all, of this pot.

On draft day, managers take turns drafting players, each selecting the player available who is most likely to aid their team statistically. Each league is a microcosm of the NFL, complete with a virtual counterpart for every player on a professional roster.

Although players can draft their team in the privacy and comfort of their own home, weathered fantasy veterans know that drafting with friends is mandatory for enjoyment.

“I love the draft. That’s the best part of the league,” said junior Brian Finci, who has been playing since he was in 6th grade.

Sitting around a table, fantasy owners pick their teams, yelling, laughing, chiding each other about ill-advised picks and lamenting when an opposing owner enhances their roster.

“You have to draft in person,” Finci added. “You have to see the look on other people’s faces when you get a steal or when they overpay for somebody. You have to rub it in their face.”

One’s managerial obligation doesn’t end after the draft, which only accounts for about 30 percent of a team’s success during the season, according to Finci. The remaining 70 percent is predicated on a manager’s knowledge of the game and its players as team owners adjust their starting lineup and augment their roster to address statistical shortcomings through a series of trades, and free agent signings. On Sunday, managers reap the benefits of their shrewd executive decisions by watching their players on television.

“It gives you a reason to watch every game, and makes it compelling,” said Finci. “If I have a player on the team, it gives me a reason to watch.” The statistical fixation of an experienced fantasy owner engages them in every game, even if the score differential is immense.

One of the most appealing elements of fantasy football is its propensity for unpredictability—no matter the score or the predicted outcome, anything can happen. There are 16 match-ups in a fantasy football season, one for each week. The final scoring in a week is decided in the fabled forum of Monday Night Football. On Monday night, owners losing their respective matchups huddle around their television screens in bold premonition of a magical come back.

“I was at my cousin’s house,” Finci said. “And his team did awful on Thursday, awful on Sunday, so he was down by over 100 points. But he had Jimmy Graham, Darren Sproles and Drew Brees playing on Monday Night Football and he came back on Monday to win by three. It was insane!”

On Sept. 29, Chris Johnson, a running back in the NFL, made national headlines when he took to Twitter to silence his critics—mostly angry fantasy football owners who were upset over Johnson’s poor statistical performance this season. “Public service announcement: I can care less about fantasy football,” Johnson wrote, “Key word: fantasy. As long as we win I’m happy. I rush for 200 (yards) n lose y’all happy,” wrote Johnson who was scorned by ESPN and fans alike for his reaction.

The controversy brought the underlying contradiction of fantasy football into the limelight. There’s a fundamental conflict of interest between professional players whose prosperity depends on the fate of their team and their respective fantasy owners who need players to post impressive statistics.

In the pre-tech era, such incongruities were diffused by distance and disconnection but now that fantasy owners can gripe directly to their players via social media, questions have been raised about how negative feedback from fans will affect a real player’s livelihood—especially considering that fantasy football is, indisputably, not real.

Even so, managers steadfastly support the validity of their pastime.

“It’s just like being a fan of any other team,” said junior Tommy Fant. “You just build a really specific team. It’s a game of numbers and feelings so, in many ways, (saying that it doesn’t matter) is like telling a coach that a real game is just fantasy because he’s not playing in it.”

Owners must finalize their starting lineup before games kickoff on Sunday at 10 A.M.

“You have to think about a lot of factors,” said junior Tyler Peck who usually plays in two leagues each year, one with his friends and another with his brothers. “It’s mostly who’s hot, weather conditions, and what team they’re playing.”

Many fans attest that playing fantasy football caused them to care so much about the success of individual players that the triumphs of their favorite team receded into the rearview mirror, thus compromising their fanhood.

“I root for players that I wouldn’t otherwise root for,” said Fant. “(But) in a lot of drafts, people pick who they like. So for instance, I like the Saints, so I drafted and traded to the point where I have their quarterback, running back and tight end. If you just stick to numbers, you’re probably going to compromise your fanhood, but if you comprise a team of players you like then I don’t think you do at all.”

Experienced fantasy owners have turned drafting their team into a science, building a team that maximizes point output by addressing all weaknesses.

“Drafting a strong running back is really important because even though quarterbacks tend to get more total points, the top pure running backs are really hard to find,” Peck said. “There’s only five or six really good running backs, guys like LeSean McCoy, Doug Martin, Adrian Peterson and Marshawn Lynch.”

Businesses have turned the hobby into a significant profit. Fantasy football is a growing industry that nets tremendous sums of money from participants through a variety of techniques and coercions. Aside from the abundance of advertisements that generate profit through frequency of web traffic, websites like ESPN and CBS earn money for fantasy football by selling owners premium services.

For instance, ESPN allows fantasy managers to buy advice from a collective analysis database called Insider that prescribes lineups and projects statistics for owners. A Yahoo Finance Report estimated that the industry generates nearly $3 billion each year. The Fantasy Football Trade Association estimates that the average fantasy football manager spends $111 annually towards related expenses and spent approximately three hours each week tinkering with their roster—time that high schoolers may not have to spare.

Finci, for example, is trying to wean himself off of the pastime now that his demanding junior year has laden him with responsibilities.

“I’m running out of time and I don’t enjoy devoting my entire Sunday to football,” he said. “It’s kind of like that feeling that I have to be home to watch it and I don’t like feeling like I have to watch so much football.”