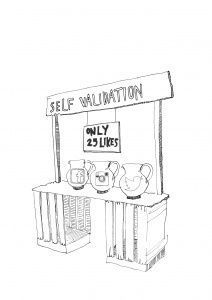

Publishing a tweet or posting a status on Facebook is an anxious experience, akin to standing on a stage in front of a thousand faceless strangers and awaiting their scrutiny.

In the wake of every comment, every posted photograph, we endure an excruciating period of expectation — nervously anticipating our due flood of likes, of approval, answering our subtle pleas for attention and recognition. Although the true ambition of each status is shrouded by a timeworn façade of conventional casualness, every post begs for acknowledgement.

So we sit and watch, refreshing the page as fervently and as frequently as an economics student reopens Market Watch. Should time flitter away and leave our post lacking the appreciation we assumed it deserved, a cutting, self-deprecating doubt seeps into our thought process. Is it because they don’t like me? We ask, horrified lest our conscience answer us. Did I say something stupid?

The inevitable product of this social media environment is a collection of children, young adults, and even grownups that, subjected to pressure, are desperate to salvage their ego from this manifestation of self-doubt.

One might suggest a rationale boycott on such mediums but the temptation of claiming the spotlight for a few precious hours is too tempting to abstain. Resisting the seductive croon of the keyboard is nearly impossible, especially after — like an addict —we have tasted social media triumph for the first time. What satisfaction to bask in the collective amusement of ten dear friends! How euphoric to know that a hundred faceless “friends” approve my picture! So, like gamblers glued to our own personal slot machine, we roll the dice again — betting our livelihood — gradually investing the entirety of our privacy and individuality.

Although I am not a frequent poster on Facebook, I probably waste half an hour each day scrolling through pages of statuses, each seeking to be deeper, wittier, or more indie than all the others — each a careless representation of the minute-to-minute adolescent thought-process — thoughts so profound that they had to be written down immediately, revised (probably enduring more drafts than an English essay), and packaged for mass consumption. Each wall post, each tweet is a representation of who we are, like our soldiers on the social media battlefield, staking our claim for legitimacy. Therein lies the problem.

We are engineers fine-tuning the gears of our mind. We are scientists empirically prodding our beakers. We are marketers, tirelessly studying the demographic of our public so that our advertisement campaign doesn’t fall on deaf ears. We are cunning contrivers, hopeless mockingbirds, shrewdly superficial in our regurgitation of accepted material.

Scroll down your news feed and the evidence is everywhere. Behind every “truth is” status, every “ask.fm” uproar, there is an ego conditioned to crave attention.

The vast majority of Facebook posts are photographs — each carefully concocted to illicit the most positive reception. For example, “Here’s me with my friends. Look how many there are! Look how happy we all are to be together!” or “Here’s me playing sports. Look, I’m athletic” or, ‘Here’s me with my dog. I’m sensitive and love animals!” Each photo, each comment, each status, is a representation of who we are—so each message we send out to the public must be properly filtered and adequately refined to exhibit ourselves in the way we want to be seen by our peers. It’s an offense of which we are all guilty.

It’s difficult to prescribe an anecdote for this disease. We are products of this era, unable to tinker with the reactants on the opposite side of the chemical formula. In concept, I am fervently opposed to the narcissism and insecurity that governs many (but certainly not all!) Facebook posts. In practice, I’m quickly becoming a Twitter addict (follow me @theBlakeShow12). There’s something very appealing about indulgently publicizing my every thought and thus developing a fairly representative documentary of my deliberations.

Similarly, I recognize the appeal and even the practical usages of other social mediums. Many will likely argue that I’m over-analyzing an innocent practice. Many will insist that Facebook is merely a tool of communication as benign as a telephone or a mailbox. But what these people neglect is the reality that we don’t use Facebook to communicate. We have phones for that. Instead, we use Facebook to broadcast our lives in the most favorable way possible. We use Facebook as a tool of comparison. Who has ever been anxious about something they sent in the mail? Frightened that they will be negatively judged about the contents of a phone call?

Doubtless, our egos are now — and for the rest of time — inescapably tethered to our online identity. But Facebook and Twitter should be used as a means of communication, and satisfaction — not as a forum for self-indulgence, subject to the petty comparisons of the insecure.