On July 12, California’s State Board of Education adopted a new, highly controversial mathematical instructional framework detailing what public school students should accomplish from kindergarten to 12th grade. It took four years, two public hearings, thousands of public comments and three revisions before the board could finalize the new framework. While it is only a guideline, a new curriculum will be designed around the framework’s recommendations over the next two years.

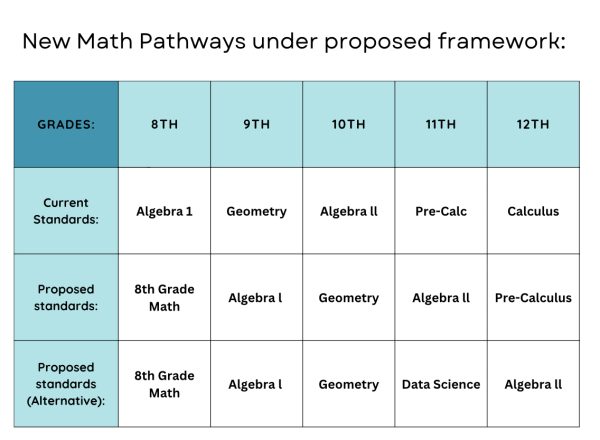

Two aspects of the new plan are still being debated today. First, the plan discourages school districts from teaching Algebra I in eighth grade. Students would instead be encouraged to wait until ninth grade to start algebra, as older students would be better able to grasp the concepts, even though this delay means they would be unlikely to take calculus in high school. Students like senior Jacob Escamila believe that doubling up on high school math courses, like Algebra I and Geometry, to address this concern may be too difficult for most students.

“A lot of things wouldn’t make sense because you learn a lot in Algebra I that you use in Geometry, like factoring, sine and cosine,” Escamila said.

By not separating eighth-grade students based on perceived ability, more students may be encouraged to pursue math and other STEM areas later on. However, students not taking calculus in high school may have a harder time getting into elite colleges and majoring in STEM fields.

A second area of debate is the framework’s support for taking data science courses like statistics instead of traditional math classes in high school. By illustrating how mathematics connects to daily life via data science concepts, the framework’s supporters anticipate students will become more interested in math. In fact, since 2020, California public universities have allowed students to swap Algebra II for data science courses.

Sonoma State University mathematics professor Ben Ford, who is one of the guidelines’ creators, supports the need for broader student participation in math.

“The people who advocate for traditional methods see the goal of math instruction as finding the brilliant ones and helping the other ones just get through life,” Ford said. “We’re thinking about the people we miss. That’s the motivation for a lot of us working on the framework.”

Escamila believes math would be easier for students if they were taught how to apply math concepts in the real world.

“People dislike the things we learn in class because we’re never going to use them — we never go over the real life applications,” Escamila said. “[Doing so] would make me more excited about math.”

But others are concerned that data science courses do not properly prepare students for college level math. A significant majority of Black faculty members in University of California (UC) STEM departments believe substituting data science for Algebra II harms students of color by representing “off ramps from pre-calculus and calculus, and thus off ramps from many STEM degrees … making students coming into the UCs very underprepared for our courses.”

One thing educators agree on is the need to improve California math instruction. On the 2021- 2022 California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress test, only 67 percent of Redwood 11th graders met state standards in math. Minority and disadvantaged students performed worse with only 43 percent of Latino students and 36 percent of socioeconomically disadvantaged students meeting these standards. Test results confirm the widely shared belief that traditional approaches to teaching math have yielded poor results.

![“[The Scotty Lapp Memorial Skatepark signifies that] Scotty’s energy, fun vibes and spirit will live on forever,” Jason Lapp said.](https://redwoodbark.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/346E3938-2C25-4CBB-9D6B-0ED4BD4A242A_1_105_c.jpeg)