Consider the last movie you watched that left you in awe. Perhaps it transported you into another world, leaving you to rethink your reality. Or maybe it felt too real, as though whatever you just watched could actually happen to you at any moment. When exactly was this? Maybe a couple of months ago, or a few years. And where did you watch it? There’s a good chance it was not in a theater.

Right now, the film industry is in a state of uncertainty. Actors are on strike, remakes of the same movies are getting mass-produced and theaters remain deserted. Viewers are left to question what’s next. Is the film industry in a state of decline or transformative change?

A lack of innovation is one issue that seems to be hurting the film industry with every passing year. In the past, movies broke boundaries and caused conversation. However, movies today cater to short attention spans and die-hard fan bases, on which the industry is dependent for commercial success. David Minhondo, who teaches History and the Appreciation of Film course, expressed this sentiment.

“I think history is going to judge [the film industry now] as the age of the remake because most movies are either remakes or superhero films. What that says to me is that the industry is struggling. [Filmmakers] are only making films that they know will at least have a decent return,” Minhondo said.

It seems, however, that production companies’ strategy for capitalizing on franchise films has finally met its demise as audiences grow weary of the constant repetition. Senior Hannah Ritola had once been a fan of franchise films, crediting the Harry Potter series to be her inspiration for wanting to pursue a career in film writing. In recent years, however, Ritola has noticed a change within herself.

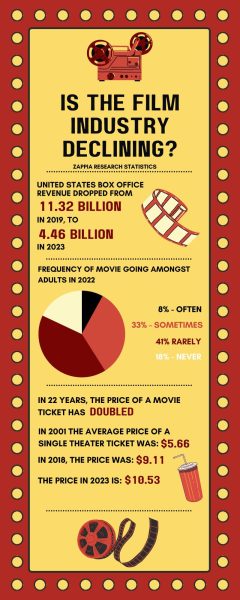

“I only go to the movie theater as an occasional activity with my friends. I feel like I’m just not as interested in going to see a lot of big blockbuster movies. You’ll hear people talking about Marvel movies or just a general decline in quality because [studios] are mass-producing them and I’m not going to spend $14 on that kind of movie,” Ritola said.

Ritola is not the only one who feels this way. In fact, companies that have typically dominated the industry in viewership have felt the effects of an uninterested audience in recent productions. Just this year, Disney’s Chief Executive Officer, Bob Iger, announced that there would be a pullback in content spending for Marvel and Star Wars products, both incredibly financially successful franchises. Iger claimed that these cuts were in response to the recent failure of films such as “Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny,” “The Little Mermaid” and “Elemental,” which all fared poorly at the box office. Production companies’ failure to understand their audience’s discontent might just be the reasoning behind this decline in innovation. Diana Sanchez, documentarian, film programmer and the education program manager for the California Film Institute, noted this trend.

“If you’re feeding audiences films that don’t make them think, connect, or consider other voices and their stories, they will adapt to that and won’t react to whatever is coming up next,” Sanchez said. “If audiences aren’t reacting to something, and being passionate about it, I think that then you know there is a lack of creativity from filmmakers.”

A decline in interest in movies and moviegoing cannot only be attributed to this reliance on franchise films and remakes. COVID-19’s impacts have been long-lasting, as regular moviegoers were forced to turn to the very streaming platforms that are being blamed for this decline we are now facing. For Minhondo, years of teaching experience have allowed him to witness the change in youths whose relationship with film has been dramatically impacted by COVID-19 and compare it to years past.

“Many of my students now have never been in a theater and watched a horror film screaming with 100 people at the same time, rolled over laughing because of something that happened in the movie or just felt so compelled at the end of a movie to just stand up and clap with the rest of the theater towards an electronic screen; there’s a collective element that gets lost,” Minhondo said.

The outlier to this decline was the sudden social shift that erupted following the release of two highly influential movies of the summer: “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer.” For the first time in years, people gathered at the theaters in high spirits, dressed in elaborate costumes, united by the anticipation of a good movie. But what separated these movies from the rest? The answer lies in the refreshing subject matter of the two films, as Ritola described.

“[‘Barbie’ and ‘Oppenheimer’] are of course really interesting and fun, but they also have a lot to say about things going on in the world. You can tell there’s care and detail put into every single aspect of them,” Ritola said.

The complex conversations on what it means to be a woman discussed in “Barbie” and what determines if a person is truly evil in “Oppenheimer” are in direct contrast with the same cliche messages we have been receiving in recent works. Lovers of film and average moviegoers, young and old, fell in love with these revolutionary movies, sitting through hours of high-quality storytelling, defying previously held notions about today’s consumer habits, according to Sanchez.

“What we see in theaters really reflects what audiences like and how audiences react. And I think what we saw with ‘Barbie’ and ‘Oppenheimer’ was such a revolution that all these people came into the theater, really liked the films and were there for their favorite directors,” Sanchez said.

It’s moments like these where we see that a societal passion for film isn’t completely lost — and that perhaps we aren’t in a state of decline but rather a state of transformation. Filmmakers are working to keep the industry alive and thriving, and the California Film Institute’s Mill Valley Film Festival is just one example of that dedication at work. The festival took place from Oct. 5 to 15, featuring films from all over the world, including local filmmakers showcasing a plethora of genres.

Sanchez and Minhondo are just some of the many lovers of film who are persistent in inspiring an appreciation for film within Gen-Z and future generations. To achieve this, Minhondo believes that more needs to be done.

“This is my 10th year here, and this is the first year ever that film did not have enough signups to run a class and out of a student body of 1,800 people to not even have 25 students that want to learn about the history of movies shows me that there’s a big cultural shift underway,” Minhondo said. “I tell students to give movies a chance. Put your phone away when you’re watching them so you can really immerse yourself. In this art form, good movies take you on a journey. Allow yourself to go on this journey.”