Nextdoor is a popular social networking site that serves as a virtual neighborhood hub and a key platform for connecting community members. Founded in 2008, the app gained popularity as a way for neighbors to stay in communication, find and receive help with tasks, ask questions, reach out to local businesses and promote community safety. The app’s user base has skyrocketed since its creation, with a current total of 75 million global users.

The Teen Perspective

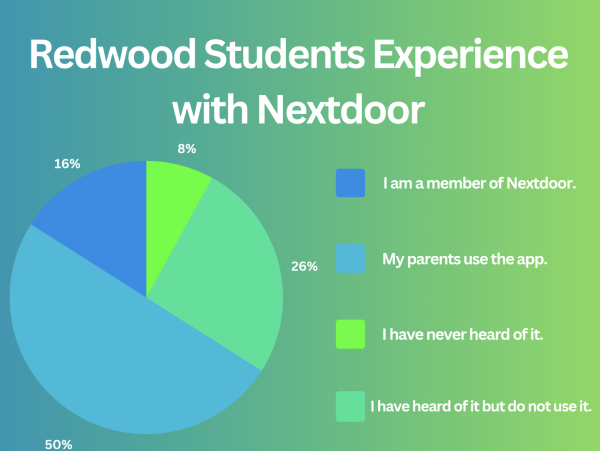

Despite the app’s good intentions, many local teens have felt negatively impacted or targeted by Nextdoor’s ability to expose individuals. While the posts often hold validity, some cases have sparked a conversation about the morality of posting about teens publicly when the single post can’t tell the entire story.

This past month, junior Henry Behrens and his friends were posted on Nextdoor with a caption including the lines “hazing a friend … it looked cruel and inhumane.” Behrens and nine other juniors were participating in a punishment for fantasy football in public in the Paradise Cay Neighborhood. At the beginning of the football season, the friends had agreed that the person with the losing team would be subject to a punishment: being tied to a chair while the other friends poured store-bought products, such as milk or eggs on the individual. Though a gross and unpleasant punishment, it was one consented to by all members. However, when a local boat owner, Stacy Newcomer, saw the punishment happening in the marina, she snapped photos to post on Nextdoor.

A lengthy explanation of what she had witnessed and photos of the teens’ faces were posted to the app, where it sparked local attention, receiving over 200 comments and reactions. To Newcomer, it seemed that the other kids were bullying Behrens, as he was on the receiving end of the punishment.

Some commenters joined the conversation, saying they hate “this type of punk behavior.” Another commenter under the name Billy McLean even suggested violence. McLean compared the mess left behind from the fantasy football punishment to the mess left behind in Lake Tahoe after July 4, saying, “those people should be shot.”

Other neighbors came to the Behrens’ defense, arguing that minors’ faces should never be posted online. Newcomer received numerous requests to take the post down. She edited the post a few times, eventually blurring the faces of the teens pictured. The post was taken down by Nextdoor a few hours later.

Other neighbors came to the Behrens’ defense, arguing that minors’ faces should never be posted online. Newcomer received numerous requests to take the post down. She edited the post a few times, eventually blurring the faces of the teens pictured. The post was taken down by Nextdoor a few hours later.

Following the incident, during the first few weeks of school, the boys involved were taken out of class individually to go into the principal’s office to discuss the event. Behrens expresses mixed emotions regarding the incident and how Nextdoor dealt with it.

“I think Nextdoor has some good features, but the people that use it, and spend their day commenting [create a culture of complaining about teenagers]. It makes the app a total waste,” Behrens said.

Behrens is not alone in his sentiments, as other teens in the community feel that the app is filled with vapid complaining. Graham Weir, a junior and Nextdoor neighbor, used to be an avid user of the app and would frequently scroll through it when he was bored.

“I was introduced to Nextdoor [by] my mom because she [thought it was] a joke,” Weir said. “She explained that people [would] complain and [share] funny stories on [Nextdoor].”

Weir also expressed that he found issues with minors being posted without consent and shared that a few of his friends had been posted about on Nextdoor.

Incidents like the one involving Behrens pose the question of how Nextdoor prevents the spread of false accusations and misinformation.

Preventative measures

According to local parent and Nextdoor’s Chief Executive Officer (CEO), Sarah Friar, despite

Nextdoor’s sometimes unfavorable reputation among youth, the app does take preventative measures to protect users. Friar has been the CEO of Nextdoor since 2018 and she has worked hard to emphasize the app’s primary purpose.

“People look at Nextdoor for three reasons: They come for trusted information, to get help and to create connections online that they can then take offline,” Friar said. Friar also explained that numerous measures are taken to ensure the online safety of all neighbors.

According to the Nextdoor website, 92 percent of all reported posts on the platform are reviewed by community moderators, who ensure that a post is not slandering anyone. If it is, the post will be removed. Nextdoor also uses generative AI to make sure that the app remains a safe space. For example, users who craft a seemingly targeted or harmful post are sent a “Kindness Reminder,” which reminds people to use thoughtful language and think more carefully before hitting the post button. “Constructive Conversation Reminders” are also sent out when comments on a post seem to be sparking an unproductive argument.

Newcomer has been using Nextdoor for a long time to stay updated on her neighborhood. She is a big proponent of the app, as she believes it’s an excellent tool for ensuring personal safety and staying informed.

“If I were a parent, I would want to know what my kids were out and about doing…it is important to be aware of these situations. [The fantasy football punishment] was the first time I ever posted calling someone out,” Newcomer said.

Additional measures have now been taken to ensure no single person is targeted or slandered on the app.

“We have made it harder to post about safety issues on purpose because we are mindful of making sure Nextdoor stays a welcoming platform,” Friar said.

Nextdoor’s website now says that “harmful content” only accounts for around 0.2 percent of posts.

Community Perspective

Is it Nextdoor’s responsibility to fact-check posts, or is it the responsibility of the neighbor? And how does misinformation or simplification of facts harm our community?

A recent Nextdoor post aimed toward the Redwood yearbook sparked major local commentary. The post was titled, “Redwood High Excludes Senior with Special Needs,” and was written by parent Janet Lewin. In her post, she said that her daughter had been left out of the yearbook after her senior year because of her special needs, saying that she was “outraged by this careless exclusion of [her] incredible daughter.” The post received over 300 comments from enraged parents and community members, mostly supporting the family without further questioning the impetus for the exclusion.

The post lacked some crucial information and resulted in students, teachers, administrators and community members receiving aggressive feedback online. What community members did not know was that the yearbook class was cut in 2022 due to low enrollment, and since then has been run as a club with several student editors. According to yearbook sales representative Brooke Renna Pang, this meant they relied on an automated system to filter photos and names into the book. Lewin’s daughter was not an enrolled Redwood student but was under the umbrella of the Marin County Office of Education (MCOE) in the special education department. Although systemic changes should be made to integrate MCOE students into the Redwood community, the whole story was not told by the short Nextdoor posts, leaving yearbook staff and volunteers victim to hundreds of complaints from the community.

Whether you are a teen, a parent or a neighbor, according to Friar, Nextdoor’s goal is to make effective and positive changes in communities. The platform can be used when looking for a job, organizing neighborhood events or getting involved in local news. But when used to share misinformation or biased accounts, particularly about minors, it can have unforeseen effects. Ultimately, it is up to users to conduct themselves with integrity and kindness towards others and help inform others so individuals do not miss important perspectives.

“When you see a post where you feel like your demographic is not being treated well, have a constructive conversation,” Friar said.

If we all are reminded to treat our neighbors with kindness and help out others in need, we can make a real change with Nextdoor, and maybe erase some of the venting or complaining that often clouds the true intentions of the app.

“There is a way to change the world, one neighborhood at a time,” Friar said.