Drive up the side of the Marin Headlands, past the towering Golden Gate Bridge, and there lies the Marincello trail — a rugged path that winds through pastoral landscapes. The view is strikingly bare: a vast expanse of deep blue ocean extending as far as the eye can see. It is almost inconceivable for one to fathom that this very land of unspoiled terrain was once marked for a massive suburb, a bustling community that never came to fruition.

In the early 1960’s Thomas Frouge, a developer from Bridgeport, Connecticut, had a fascination for the land of Marincello and the grand development he could make upon it. Eager to realize his fantasy, with help from the Gulf Oil company, he purchased the 2,139 acres of land and made plans for this new Marin community, to be named “Marincello.”

Senior Gabby Hoeberichts, when learning about Marincello in her high school class, also became fascinated with the vision of the potential community sparking a passion project.

“I’m in a program at [Tamalpais High School] called Social Enviromental Justice and Action (SEJA). My teacher mentioned [Marincello] in one of our classes and it hooked me,” Hoeberichts said.

Hoeberichts went to the Mill Valley Public Library and asked if they had a folder on Marincello. She went in with the expectation to not find anything, but instead discovered old articles from meeting minutes from the old board of supervisors, emails and other remnants of Marincello’s past.

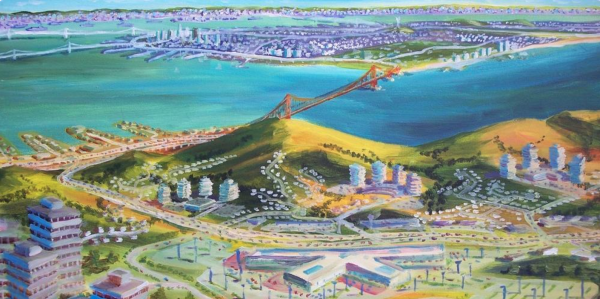

Frouge initially envisioned Marincello as a suburban utopia, a community that aimed to transform the Marin Headlands into a thriving residential area. The grand vision included 50 apartment buildings, 30,000 residents, thousands of townhomes, one hotel and a shopping mall, all connected by a single road, Marincello Street, which would lead off from the Golden Gate Bridge.

He did not want this land to be like other suburban communities in the U.S. Frouge wanted all of the apartments and homes to be built with an “open space architecture” that would blend into the vast landscape of the Headlands. According to Bay Nature, Frogue made the promise that Marincello would be a carefully planned city and would not fall siege to the mistakes of other dense suburbs around the country.

At the time the project was proposed, a small group of activists, known as the Golden Gate Headlands Committee, opposed the development. They presented a petition bearing 6,000 signatures to the County Board of Supervisors regarding the Marincello project, but it was disregarded. A subsequent petition submission was discredited when the county invalidated 300 signatures and proceeded.

In Nov. 1965, Marin County officially granted approval for Frouge’s plan, giving the green light for building. Soon after, gates were swiftly erected at the base of Tennessee Valley, what was to be the future entrance to the city. Bulldozers began carving out a sizable five-lane boulevard up the mountainside, intended to serve as one of Marincello’s primary thoroughfares. These developments signaled, in 1965, that the metropolis’ construction was now well underway, with no obstacles in sight.

Filmmaker and director, Nancy Kelly, heard about the Marincello story and wanted to feature the story in a film, “Rebels with a Cause.” Her film helped to inform many new Marin residents about the history of the open space. She highlighted the resilience of Marin legend Robert “Bob” Praetzel in defending the land as an attorney.

“[Marincello] never would have been saved without the efforts of Bob Praetzel. That was true because the other lawsuit, they lost, and the other developer won,” Kelly said. “Bob had found that they didn’t give 10 days for public opinion [regarding Marincello], they only gave seven.”

As highlighted by Kelly’s film, the efforts and sacrifices of Praetzel and other lawyers went financially unpaid. Additionally, they encountered significant challenges and adversity.

“They had families. They were young men with young families. They all had day jobs. They managed to fight for this. They were doing this at a time when environmentalism was [barely] a word,” said Kelly.

By 1966, Marincello’s budget had swelled far beyond its initial estimate of a 20-year, $250 million endeavor. Gulf Oil executives, the project’s primary financial backers, grew increasingly doubtful of Frouge’s Gulf Oil Land Development Division and their plans for Marincello. Arguments erupted within the company, and a legal showdown between Frouge and Gulf Oil grew large.

This pause in progress allowed Douglas Ferguson, Bob Praetzel and Marty Rosen, three lawyers closely monitoring Marincello’s development, to intervene. Representing the City of Sausalito, they were incensed by the legal shortcuts taken to expedite construction and launched a formidable lawsuit against Marin County, Frouge and Gulf Oil. Their argument centered on the improper zoning of Marincello in 1964, contending that the public had been granted a mere seven days to review the zoning, rather than the mandated ten.

The legal battle marked a turning point in Marincello’s fate. Ultimately, the National Park Service acquired the land in 1975, putting an end to the dream of Marincello. The proposed suburban community would remain unrealized, and the Marin Headlands sustained, untouched by the specter of suburbia.

The story of Marincello serves as a cautionary tale: A reminder of the enduring struggle between development and preservation in the face of evolving urban landscapes.

According to the Sept. Bark Survey, 44 percent of Redwood students visit the Marin Headlands at least once a month. Junior Sadie Hann frequents the Marin Headlands with her family and friends. “It is just a really peaceful [place] and a good way to disconnect,” Hann said.

The Marin Headlands, once threatened by urban sprawl, now stands as a testament to the power of environmentalism. It offers visitors a chance to experience the unspoiled beauty of nature, with hiking trails, scenic overlooks and a deep connection to the land’s rich history. Marincello may have failed to become a suburban utopia, but its legacy lives on in the natural beauty of the Marin Headlands, a place where nature and history converge in harmony.

Explore an interactive map of the Marincello project