It’s okay to be okay

May 6, 2023

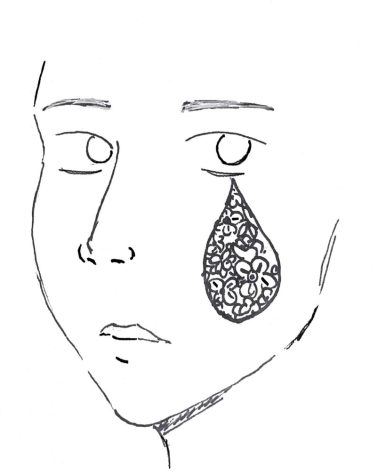

A girl online dabs Vaseline under her eyes; she paints copious amounts of cream blush across the bridge of her nose; a watery line of mascara runs down her poreless cheek. This is the expectation of the “crying girl makeup,” a representation like no other of the recent glamorization of sadness. If nothing else, we know that she is pretty when she cries.

Such is the state of modern pain — equal parts romanticized and aspirational. It’s no coincidence that the rise in the aestheticization of sadness corresponds with the pursuit of mental illnesses as new forms of social capital. Be it in the trivialization and widespread use of terms such as “kms,” the acronym for “kill myself,” or in the prettily lit and sequined aesthetics of mental illness in “Euphoria,” suffering is on the rise.

At the same time, mental health is more widely recognized than ever. In a 2018 survey by Pew Research, teens listed anxiety and depression as top issues among their peers. The multitudes of glamorized portrayals of sadness in media — the book “My Year of Rest and Relaxation” and Lana del Rey’s “Sad Girl,” to name a few — have in some ways provided an outlet for the expression of mental health issues and a greater awareness of sadness as a real aspect of the human experience. We have become more comfortable with understanding sadness and pain as essential parts of life. We have learned that it’s okay not to be okay.

Too often, however, these representations of sadness tend toward the romantic rather than the realistic. With such portrayals comes a view in which pain is placed on a pedestal, in which it is seen as necessary, as a means to a more authentic experience of life. To be beautiful, artistic or insightful — under today’s interpretation, all require some level of misery. “Beauty is pain,” goes a common mantra; the trope of the tortured artist represents a longstanding correlation in our society between cynicism and intelligence. “Sittin’ on the sofa, feelin’ super suicidal,” sings Lana del Rey on her 2023 song “Candy Necklace.” But trauma isn’t necessary to be intelligent, self-reflective or any of the traits that pain could seem to impart upon its recipients.

In recent years, mental health struggles have, for some, become a source of identity. Jinan Jennifer Jadayel, co-author of a 2018 study on the glamorization of mental illnesses, spoke about her research on the influence of social media on mental health awareness.

“People label their sadness as depression and their nervousness as anxiety when the problems that they’re facing often don’t reflect those psychological problems,” Jadayel said.

This search for meaning in emotions — by equating temporary emotional states with mental illness — has often proven a harmful pursuit. A participant in the 2018 study elaborated on his experience with depression and its portrayal online.

“I resorted to the internet in order to try and find something I could relate to… The pictures were all driving me to believe that I was alone and that I didn’t belong socially. The seemingly deep and poetic imagery on social media definitely contributed to aggravating my mental health problem,” he said.

The concept of “good damage” in “Bojack Horseman,” for example, represents this striving for trauma as social capital. The character of Diane, a writer, finds herself in crisis when she isn’t able to transform her suffering into an insightful work of literature.

“That means that all the damage I got isn’t ‘good damage.’ It’s just damage. I have gotten nothing out of it and all those years I was miserable was for nothing,” Diane says. “I could have been happy this whole time and written books about girl detectives and been cheerful and popular and had good parents, is that what you’re saying? What was it all for?!”

As Diane discovered, sometimes suffering can be just that — painful from every standpoint, resistant to transformation and unwilling to be romanticized. And yet her initial perspective on sadness is no coincidence; it is precisely from the glamorized portrayals of suffering that pain has falsely emerged as something aspirational.

Certainly, there are circumstances in which the representation of sadness can be beneficial. The emotional connection triggered by tragedies, for example, can allow viewers a greater understanding of the relationships in their own lives. Sad songs can also open the doors to a wide range of emotions. According to a study by University of California (UC) Berkeley, participants who listened to sad music included nostalgia, peacefulness and wonder in their emotional responses. Indeed, by limiting the response induced by “sad” music and movies to just one emotion, we may be stifling a better understanding of our own lives. According to a study by UC Berkeley, accepting rather than judging or suppressing emotions can lead to less stress and better psychological health. Similarly, it is in embracing sadness for what it is — an emotion rather than an aesthetic — that we can truly improve our mental health, far beyond the years of pretty crying to Phoebe Bridgers songs.

Sadness will always be a part of life. Yet as we grow comfortable with experiencing the more painful aspects of our lives, we shouldn’t shy away from the potential found in positivity and joy either. It’s okay not to be okay, and it is just as okay to be okay. Damage is not a replacement for meaning; suffering is not a requisite for beauty. It is through acceptance, not romanticization, that we can fully experience our emotions — and with them, the world.