Senior Olivia Kontinnen thought she had the whole college process figured out. Committed to playing soccer at the University of Miami, Kontinnen applied to other schools as an afterthought and was singularly focused on attending Miami.

However, when Miami’s financial aid office did not offer the aid she had expected, she soon found herself looking at other schools.

“I didn’t get [the financial aid that] was predicted and so I’m like ‘I’m not about to pay $61,000 a year to go to Miami,’” Kontinnen said.

Kontinnen eventually settled on the University of California, Santa Barbara, which offered a more attractive aid package.

“Santa Barbara is obviously in-state, UC, and the financial aid I’m getting is incredible,” she said. “Financially, it’s a no-brainer.”

Kontinnen is not alone among Redwood seniors who have found that the realities of paying for college trump the benefits of going to what otherwise would have been a top choice school.

Seniors Wynn Taylor, Zoe Poynor, and Angus Barkow all had paying for college at the forefront of their minds when they started the college application process.

Poynor, who will attend the University of Southern California, is paying for college through a combination of a half scholarship from the school and various grants and loans. She said that the scholarship she received from USC definitely played a big factor in her decision, but was by no means the only reason.

“USC was towards the middle or bottom of my list, but it pushed it up to the top three,” Poynor said.

Taylor also circled back to money as a factor in his decision on where to attend college, explaining that he avoided UCs because of the cost of possibly having to graduate in over four years.

“UCs are known for their budget cuts and stuff so a lot of kids are forced to stay in school for five, six, or maybe even seven years,” Taylor said. “My family just can’t pay for more than four years of school.”

Because of this, Taylor applied to schools that he said are known for giving out financial aid. The University of Arizona offered him $24,000 per year and a new iPad, an offer that he said he couldn’t refuse.

According to the Project on Student Debt, the Class of 2011 finished school with an average of $26,600 in student loan debt. Taylor said he looked at the long term benefits of graduating college with very little in student loan debt.

“When I realized that I most likely was not going to my top choice college, I started questioning would it be worth it to pay $35,000 a year to go to like Michigan State or Indiana,” he said. “That $24,000 [from Arizona] can make it so I wouldn’t have to take out as much money [in student loans].”

While Poynor and Taylor received significant amounts of financial aid, both will be part of the 60% of current college students who borrow annually to cover college related costs, according to the American Student Assistance non-profit group.

Taylor said he plans to take out between $5,000 and $10,000 in loans from the government, while Poynor said she is borrowing $5,500 a year and $22,000 overall through federal Stafford loans.

Of the $5,500 that Poynor will borrow a year, $3,500 is subsidized, meaning that the Department of Education pays the interest on it while the student is in school and for six months after graduation. Poynor said her parents will pay interest on the remaining $2,000 in unsubsidized loans she will take out.

Poynor, a presumptive international relations/business major, said she is not worried about paying her loans off.

“USC is one of those schools that when you graduate you are almost guaranteed a certain amount of starting salary, which is around $80,000, so I’m not that worried,” Poynor said.

According to Poynor, while the financial aid may have peaked her initial interest and helped her give it serious consideration, the school itself captured her heart as she learned more about it.

“Both the price and the academics and getting to know the school better pushed it to the top of the list,” Poynor said. “I think I still would have chosen USC even without the scholarship.”

Taylor said that while he is excited to attend Arizona, it might not have been his choice if money were not factored into the decision.

“I felt like I just didn’t want to place the burden on my parents,” he said. “[Paying for college is] definitely going to impact their lives greatly. They are going to have to make some sacrifices, which I don’t feel comfortable making them do.”

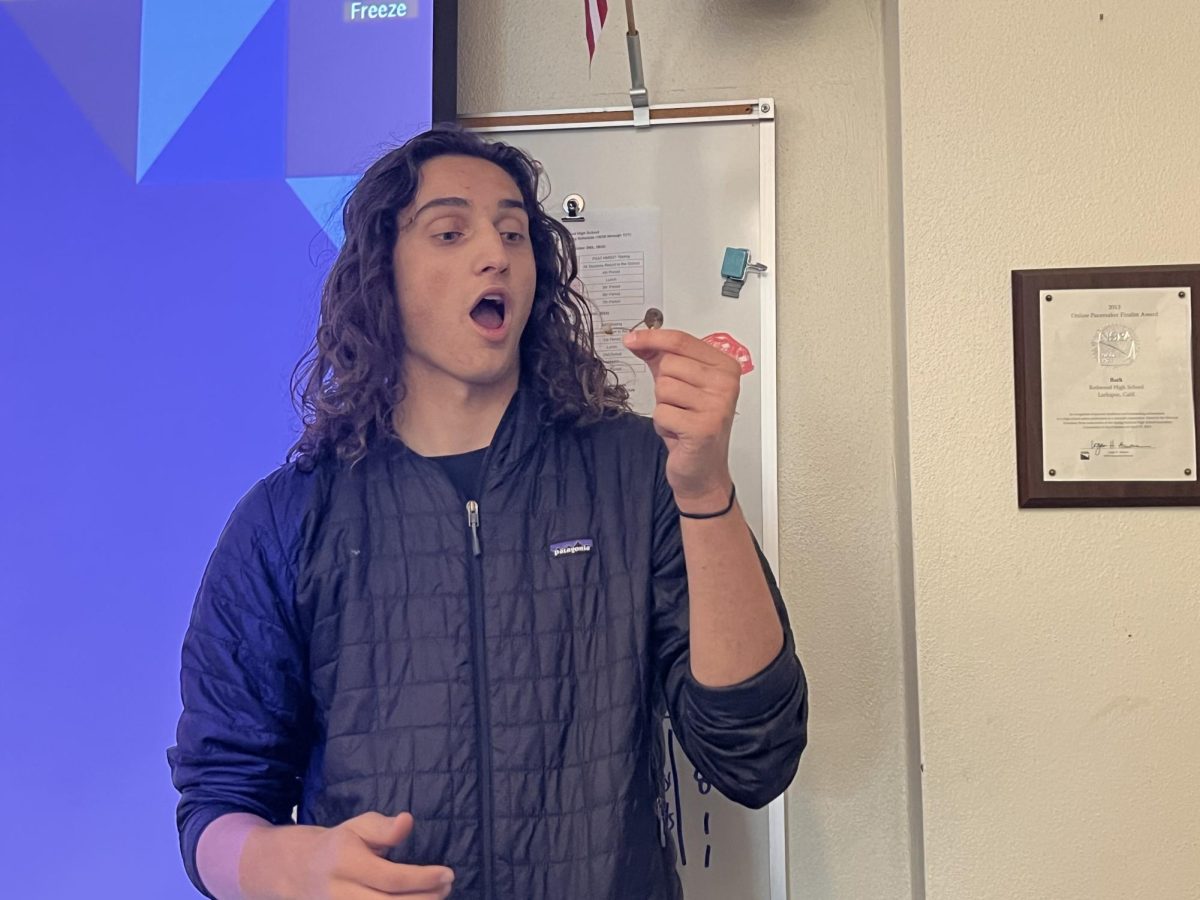

Barkow echoed Taylor in saying that his college choice of University of California, Santa Cruz was not his first choice and only came about because of his financial situation.

“Even though I actually preferred British Columbia and Wisconsin to Santa Cruz, I really had no choice,” Barkow said. “If money was not a factor, I probably would have chosen Wisconsin or British Columbia.”

He said that Wisconsin offered him just $2,000 in grants, while British Columbia offered about $2,500. UCSC gave him $14,000 in grants, and Barkow said because of this, he won’t have to take out any student loans.

For Kontinnen, attending her top choice school was also just not worth the cost. She said she felt misled by the Miami financial aid office, who predicted that she would receive much more money than she did.

“How I felt they handled the situation is that they told me I was going to get a certain amount, and once they found out I was committed, they kind of used that to their advantage and said, ‘This kid is committing, they’ll doing anything to go here now,’” Kontinnen said. “Maybe they thought it was worth it to me to pay that much, but it obviously wasn’t.”

Similar to Kontinnen, Barkow did not anticipate cost being a factor in his decision until late in the college application process and said that he wishes his parents had been more upfront with him about the reality of paying for college.

“I think the really important thing is…you have to talk to your parents and say, ‘Look, how much money do we actually have?’” Barkow said. “Our parents have this tendency to just, you know, they want to make it seem like, ‘Oh, everything is fine, we are going to take care of you.’”

According to Barkow, knowing early on in the college process one’s financial situation is important because it gives more time to look for the multitude of scholarships and grants that are available.

“So you might as well ask ahead of time, ‘What kind of sources do we have?’” Barkow said. “That way, if you don’t have that much money as a family, if you can’t afford it, you have more time to go out and look for scholarships.”

Despite the stereotype that Marin kids are so well off that they can afford to pay for any college, Kontinnen said that she believes that many Marin kids are not willing to pay an astronomical price to attend their dream school.

“I’ve talked to people who say like, ‘No, that’s too much. I’m just going to go to another school that’s either closer or in state,’” she said.

Indeed, many private colleges seem to be understanding this trend.

According to the Wall Street Journal, quoting a study by the National Association of College and University Business Officers, the average “tuition discount rate” — or the average price reduction off the stated tuition price through grants and scholarships — at private schools was an all time high of 45% for the class of 2016.

This is the 7th year in a row that the average discount rate has risen, while last year’s median tuition price for private schools increased by just 3.9%, the smallest increase in at least 12 years, the Journal said.