Pandemic unintentionally creates more equality at the UC schools

June 5, 2022

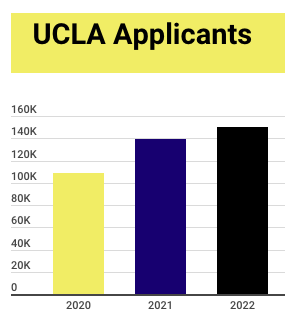

During a May 2020 meeting, the UC Board of Regents declared that ACT and SAT scores would be optional for University of California (UC) applicants. This change is just one of many ways COVID-19 has impacted applications and admissions to the UC schools. Many Americans understand how the pandemic has changed schools, work, mental health, and other aspects of everyday life. However, it has also made impacts on applications and admissions to the UC school system. Over the past year, impacts such as changes in standardized testing requirements have created more interest in applying to the UC schools and opportunities in less wealthy areas. This has led to an all time high number of freshman applicants in the 2022 admissions cycle.

Prior to the 2021 fall semester, many universities were still closed to in-person learning or enforced pandemic safety precautions for students. This unconventional college experience led many students to consider taking a gap year. Many educational researchers believe that this trend decreased overall enrollment for a period of time. National Public Radio reporter Elissa Nadoworny discussed the decreasing enrollment in colleges, stating that, “The decline of 3.2 percent in undergraduate enrollment [in the] fall [of 2021] follows a similar drop of 3.4 percent the previous year [in 2020].”

At Redwood, seniors felt a similar hesitancy in attending college during hybrid or online programs. Senior Troy Volpentest explained that students most likely took a gap year because they did not want to pay for university tuition when they did not have a chance to experience normal in-person learning.

“A lot of [students] feel no reason to be on campus, and… you’re not going to get those college experiences if you’re just in your dorm on your computer,” said Volpentest.

As a result, many students decided to wait and reapply when colleges returned to in-person learning.

According to Rebecca Koenig, an editor for an educational journal called EdSurge, “Approved gap-year requests jumped on average…from 37 to 118 among one public and two private large universities.” Additionally, deferral rates at many universities increased significantly. The effects of the increased number of students taking gap years and deferral rates showed when enrollment increased for the class of 2022 when these students applied in addition to the standard incoming class.

Becky Bjursten, a College and Career Specialist at Redwood, explained the importance of acknowledging the popularity of gap years.

“[The pandemic] has highlighted how [taking a gap year] can be a great option,” Bjursten stated.

Seniors this year are now more aware of the benefits one can reap from taking a gap year due to their popularity during the height of the pandemic. This is a development that could continue to evolve seniors’ perception on college applications in the future.

COVID-19 has also influenced the UC schools’ standardized test requirements. Universities implemented test optional, commonly known as test-blind applications, to accommodate students who were unable to take the SAT and ACT test in-person during the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, even as students are beginning to take standardized tests again, the UC schools have retained the test-blind applications.

Bjursten reinforced this sentiment and voiced that test scores and other statistics have less weight than things like extracurricular activities in the admissions process.

“It’s not all about the number. Your story has a lot to do with what you add to [the application],” Bjursten said.

The UC’s removal of SAT and ACT scores is a major step towards eliminating inequalities, such as disparities in test preparation opportunities. This action can help level out the playing field for minorities and first generation college students, especially those living in less wealthy areas who can not afford resources to prepare for standardized tests. Scott Jaschik, a founder of Inside Higher Ed, explained how income greatly affects standardized test scores.

“The lowest average scores were those with less than $20,000 in family income, and the highest averages were those with more than $200,000 in income,” said Jaschik.

With the test-blind applications, Bjursten explained how income acceptance discrepancies could be equalized.

“One of the great things about removing SAT or ACT as a requirement [is that it] has enabled so many more students to apply to [UC] schools without that barrier,” Bjursten said.

Because students in wealthier areas have more resources to prepare for standardized tests, it creates a disadvantage for students in less wealthy areas. Jose Chavez, UCSD Guardian reporter, explained that removing standardized tests is a positive for many prospective students.

“History shows that these barriers were carefully constructed to bar minorities from succeeding,” Chavez wrote in the article.

Thus, by eliminating the required standardized tests, socioeconomic barriers are being removed and many minorities and first generation students are receiving better opportunities to apply to UC schools without the burden of standardized tests.

Teresa Watanabe, a reporter for the Los Angeles Times, explained that more minorities have been accepted at UC schools and stated that, “At UCLA, for instance, 34 percent of California incoming freshmen were Black, Latino, American Indian and Pacific Islander students — the largest proportion of such groups in three decades.”

While many of the UC schools are trying to accommodate for the rising number of applications, acceptance rates will likely decrease further if trends of higher application rates continue.

Although the pandemic has undoubtedly wreaked havoc on our previous ways of life, an unintended benefit of COVID-19 is how it has increased opportunities for many applicants to UC schools. Even though the increase in applications may have driven down acceptance rates, students who are disadvantaged in standardized testing are now able to submit better, more representative applications. All applicants are now judged more on other parts of their life and education rather than a simple and often biased test.