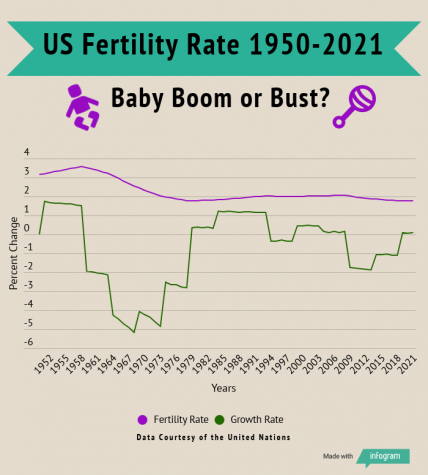

In light of growing climate concerns, younger generations are questioning the future of an overpopulated planet. On a national level, the population fluctuates for three reasons: birth, death and migration. Although the U.S. population continues to increase, the growth rate has slowed each year since 2015. In 2020, the U.S. birth rate fell for the sixth consecutive year to the lowest levels since 1979. The replacement rate to maintain population levels is 2.1 births per woman, but the U.S. currently sits at 1.6 births per woman.

Fewer children being born impacts more than just numbers. Demography, the study of statistics relating to population, illustrates the changing structure of human populations and how it affects the economic, political and environmental makeup of a country. Sociology and political science professor at the College of Marin, Robert Ovetz, believes that both the U.S. and the global population are tapering off. A decreasing population, however, does not automatically solve all pre-existing issues relating to the population size. The term overpopulation does not necessarily signify a planet overflowing with people; it refers to the scarcity of resources, which fuel discrimination.

Fewer children being born impacts more than just numbers. Demography, the study of statistics relating to population, illustrates the changing structure of human populations and how it affects the economic, political and environmental makeup of a country. Sociology and political science professor at the College of Marin, Robert Ovetz, believes that both the U.S. and the global population are tapering off. A decreasing population, however, does not automatically solve all pre-existing issues relating to the population size. The term overpopulation does not necessarily signify a planet overflowing with people; it refers to the scarcity of resources, which fuel discrimination.

“It’s hard to say what overpopulation is. It depends on what your priorities are. We also have to be careful about saying we are overpopulated because that has some eugenic consequences. What’s too many people, and what kind of people are too many?” Ovetz said.

Essentially, affluence is the primary cause of the declining birth rate in the U.S. Today, more women attain higher degrees of education than ever before, making up the majority of college students, according to The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). A study from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) found that women with at least one year of college education have sharply lower fertility windows than less educated women, regardless of race or origin. Joel E. Cohen, a professor of populations at Columbia University, explains that women who have children by their mid 20’s are more likely to avoid long educational tracks. Careers also cause women to delay having children, giving them less time to give birth while fertile. Along with the increase of women in the workforce, the ambitions of women have changed too, according to a current senior who does not plan on having children.

“I think our generation might be less inclined to want children because as times go on, women realize that their purpose is less to have children. In older times, I feel like women didn’t think they had much of a choice,” she said.

During times of widespread financial insecurity, the desire to have children decreases. Regardless of a country’s affluence, some generations may face more challenges than their predecessors. The Federal Reserve’s study on consumer finances suggests that U.S. millennials are amassing less wealth, and falling into greater debt than previous generations. Ovetz connects this financial insecurity to many millennials’ decision to not have children.

“There are no real child support or childcare systems. Women are refusing to take on a second and third [jobs.] So, the response is women are saying ‘I’m going to wait until I’m more financially secure.’ You have an older age of birth, which means fertility rates are going down because you have that much less time to give birth while you’re still fertile,” Ovetz said.

Environmental concerns also affect the decision to have children. According to an Amnesty International survey on the state of human rights, four out of 10 young people view climate change as one of the most pressing global issues. Fearful of the planet’s future, the current senior does not plan on having children for this exact reason.

“I do not want to bring children into a world that is being ravaged by so many environmental and humanitarian issues. I think if our government was able to work with scientists and put together a short-term and long-term plan that we could actually see coming through, I would feel more comfortable,” she said.

Despite enough land to accommodate a growing population, the Global Footprint Network estimates it would take five Earths to support the human population if everyone’s consumption patterns were similar to the average American. However, population is just one part of the environmental equation and does not eliminate the impacts of consumption, according to Mitch Cohen, AP environmental science teacher.

“Environmental impact is a function of three things: population, consumption and technology. If the population rises, the only way to mitigate the environmental impact is to reduce consumption, improve technology or some combination thereof,” Cohen said. “What you see is consumption going up on a global level: as less developed countries become developed, they are consuming more. We are putting a lot of hope into the technology.”

Instead of solely relying on technology to save the environment, having one less child could remove a lifetime’s consumption. Published in the journal Climatic Change, a survey of 600 people aged 27 to 45 found that 96 percent were very or extremely concerned about the wellbeing of their potential future children in a world ravaged by climate change.

“In some ways, you could say that having children might be a little selfish. It has a lot to do with personal utility and gratification. [You are] bringing someone into this world [that] is like a version of you,” the current senior said.

If more people have opinions similar to hers, the climate could benefit from the birth rate decline in the U.S. However, the question remains about what would happen to the country if it continued declining. Ovetz predicts that having fewer children combined with longer lifespans might affect the economy.

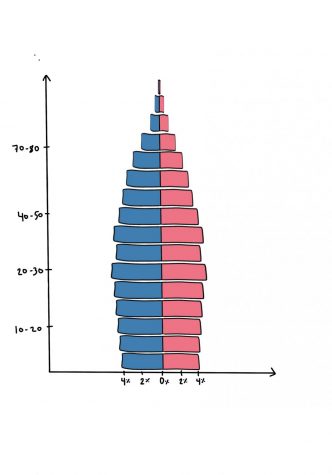

“In the global north, populations are shrinking. You have this population pyramid where the base is getting smaller and people are living longer [because of wealth]. There are all kinds of consequences for that,” Ovetz said. “For example, a lot of other wealthy countries have more generous pension systems [provided by the government] than we do. [Yet], there are fewer people paying in at the base, and [taxpayers] are covering more and more people.”

The smaller working class population, resulting from fewer children, means the U.S. has more available jobs; those currently employed actually earn higher wages. Although with fewer workers, each must work harder, Ovetz sees population decline as beneficial.

“When you have a tighter labor supply, unemployment goes down, which has an upward push on wages,” Ovetz said. “Tight labor marketing is actually good because wages have not really grown in 40 years and there are still millions of people working at minimum wage and trying to survive. I think it is a good thing that the population is shrinking.”

The consequence, however, is a less competitive economy. In order to raise the working class population without paying citizens to have kids, immigration policy must change. A 2000 simulation run by the United Nations (UN) Department of Economic and Social Affairs found that by 2050, Europe’s population is set to fall by 17 percent without migration.

“About four or five years ago, Germany took [about] two million refugees from Syria, Afghanistan, Libya. They did it for this exact reason: they have a graying population and labor shortage. It has worked out relatively well for them,” Ovetz said.

An opinion in the New York Times published in Aug. 2021 encouraged the U.S. to take similar action as Canada which initiated a Provincial Nominee Program in 1998. Based on population needs, it gives provinces a quota of immigrants to sponsor. After passing a basic background and health check, immigrants from all over the world acquire sponsorship for permanent residency. The average processing period is about 18 months, compared to the U.S. which could take years.

Another potential consequence of a national lower birth rate is its effect on retirement and social security, which Ovetz believes require reassessment.

“Medicare is on the verge of running out of money. Social security still has [about] 20 years. The demographic factors are going to cause those programs to reach the point where they are taking in just what they are putting out,” Ovetz said.

Involving the government with the birth rate does not guarantee a solution to what might come of a changing population. While birth rates certainly matter, the actions taken by U.S. citizens will do more to promote sustainability.

“Yes, population does matter to the environment; more kids, more resources. [But] I think the flip side is that the world needs educated children that are going to be able to help solve these problems,” Cohen said.

Scientists predict the earth’s population will stabilize between 9 and 10 billion people once the global fertility rate reaches the replacement rate. Without environmental action taken, whether our children will live to see that day remains uncertain.