The truth about stuttering: navigating past the media’s stereotypes

May 27, 2021

“I know exactly what I am going to say, but it’s almost like I am choking. It’s like there is something in the back of my throat,” sophomore Alec Marasa, who has a speech impediment, said.

Marasa describes stuttering as the feeling of losing control –– the same sensation one would have on an ice skating rink, where one moment you’re skating and the next you’re slipping to the ground. Despite the 70 million people worldwide struggling with stuttering and other speech disabilities, there is still a profound stigma and deep misunderstanding around what stuttering really is and how it affects people.

As Redwood students, it is essential to educate not only peers and family, but teachers and school administration as well on the truths behind stuttering. By recognizing the strength it takes to overcome speech disfluency-related challenges, students who struggle with speech can feel more accepted and confident at school.

The Mayo Clinic defines stuttering as a speech disorder that involves frequent problems with the normal fluency of speech. The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) categorizes stuttering into three different types: repetitions (li-li-li-like this), prolongations (llllike this) and blocks (—–like this). Stuttering is more complicated than many realize, affecting individuals in very different ways. Because the effects of stuttering are so versatile, misconceptions are far too common. These stereotypes continue to discredit people that have worked hard to overcome their challenges with speech.

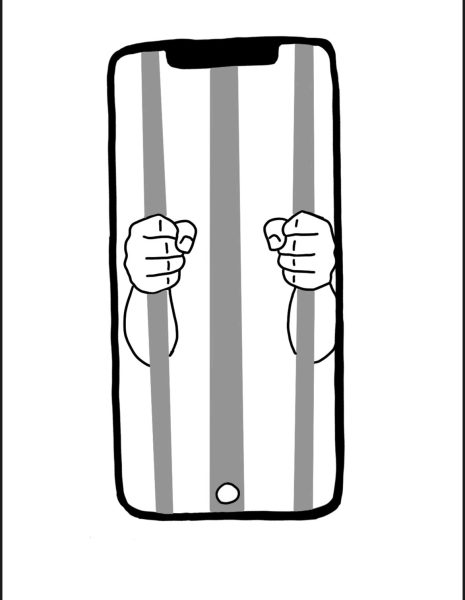

According to the National Stuttering Association, stereotypes often magnified by the media question the intelligence of people who stutter. Because social media has the ability to spread information on a global scale, this electronic highway houses a vast number of misconceptions, generalizations, myths and false interpretations often pertaining to the intelligence of those who stutter.

Myths and stigmas about stuttering deeply impact students, especially in classroom settings where everyone has their own conscious and unconscious biases. In fact, according to a 2001 survey conducted by Marshall University, 81 percent of children who stutter are bullied.

Redwood is home to a multitude of students, all with personal thoughts, ideas and biases. Marasa explains his own experiences at school, specifically highlighting how peers often treat him differently because of his stutter.

“People always cut me off. A lot of times people believe that when I think, I stutter too. I am eventually going to get the words out, [but] being patient and listening is not something I can expect from everyone,” Marasa said.

While most students at Redwood do not struggle with a diagnosed stutter or speech impediment, the fear of misspeaking during public exchanges is fairly common. According to a Cub-Bark survey conducted in February 2021, more than 60 percent of Redwood students feel an anxiety-related panic in regard to the fear of messing up when called on to speak in a large group, a feeling felt by those with speech impediments even during casual one-on-one exchanges.

There are many hurdles those who struggle with speech disfluencies work to overcome. In fact, social media is not the only culprit of perpetuating the stuttering stigma. According to Barry Harbaugh from Slate magazine, filmmakers often project false and unhelpful theories about stuttering instead of accurately educating their audience. According to Harbaugh, movies, books and other forms of social media often portray a person who stutters as someone who has the inability to present themselves (whether it’s through lack of social skills or limited intellectual ability.) Not only do such stereotypes misconstrue what it means to be a person who stutters, they also condone normalizing the use of inaccurate and hurtful stereotypes through film.

Political figures such as President Joe Biden have openly spoken about their experiences with stuttering, along with the communication barriers they face. Biden in particular touches on how the media misinterprets stuttering, creating labels that are incredibly hard to get away from.

“[People who stutter] are thought to be slow-witted. We are thought to have emotional problems,” Biden said in a 2008 speech. He frequently expresses his own frustration with the media, wherein many platforms frequently correlate stuttering to signs of mental decline. This is false, as, according to the National Stuttering Association, people who struggle with stuttering and other kinds of speech disfluencies are as capable and intelligent as others.

As fellow students, we can help to create more comfortable spaces by offering support while being more educated, open and aware about certain stigmas that misinterpret the realities of stutters and speech impediments. Because there is only ever a small part of people that we actually see, it is vital to try to separate one’s biases from fact. By recognizing the expansiveness of social media, pinpointing and spreading only the truth will remain an upward battle –– but one worth fighting for. As peers it is important to stay patient, aware and educated. Through educated minds, students who struggle with such speech disfluencies can hope to feel not only more understood, but comfortable.