Dear teachers, let’s include the introverts

May 4, 2021

“You’re quiet, aren’t you?”

“You’d seem friendlier if you weren’t so quiet.”

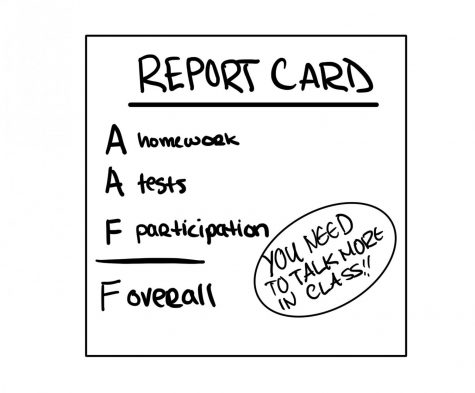

“Be less quiet during class and you’ll get a higher grade.”

Quiet. According to others, this word encompasses my entire introverted identity. Usually said in a demeaning tone, it indicates that being quiet is not ideal. Even in school, a place that should cultivate individuals’ strengths, there is a negative connotation on the less talkative students for not repeatedly raising their hands. I often wish to change the fact that I’m not extroverted, due to the lack of support from my high school.

Introvert Susan Cain, author of multiple books on introversion, recognizes Western society’s value placed upon extroverted tendencies.

Introvert Susan Cain, author of multiple books on introversion, recognizes Western society’s value placed upon extroverted tendencies.

“Our most important institutions — our schools and our workplaces — are designed mostly for extroverts and their need for lots of stimulation,” Cain said in a 2012 TED Talk.

Because of this, introverts feel out of place. Psychologist and University of Melbourne professor Dianne Vella-Brodrick found that introverts are less satisfied with themselves the more they wish to be extroverted. If they are able to accept their differences, which is hard in an extrovert-favored world, they’d be happier.

Beginning in schools, extroversion is placed on a pedestal. A February 2021 Cub-Bark survey found that 53 percent of Redwood students believe their introverted or extroverted identity affects their ability to engage in classes. The popularity of “collaborative learning,” shows societal favoritism for extroversion. Pre-pandemic classrooms had desks pushed together for convenient group work, forming noisy, overstimulating environments. Similarly, the growing importance of in-class participation grades puts pressure on students to talk more, which can be difficult for introverts.

These practices are meant to teach students to be more extroverted, a popular opinion linked to the misconception that everyone must learn people skills. However, introversion and extroversion are fixed functions of the brain. While extroverts become energized with a rush of dopamine, introverts feel overstimulated and exhausted and instead prefer a different neurotransmitter that causes them to enjoy turning inward in calmer environments. Instead of trying to teach the unteachable, society, especially schools, must adapt to these neurological differences that relate to our response to stimulation.

Online schooling seemed like an introvert’s dream and extrovert’s nightmare. Yet, Zooming affected everyone differently, no matter how introverted or extroverted. One positive was the chat feature that, for the teachers who allow it, invited everyone to participate without attention. It was great for someone like me who hates being in the center of attention. However, as introverted as I am, I hated online schooling as it drained my energy and removed personal connection. In contrast, some of my most extroverted friends loved schooling from their homes and dreaded going to in-person classes.

No matter the personality type, socializing in person is preferable. The ability to mute or stop the camera gave the conversation an unnatural and awkward flow, although leaving oneself unmuted could also be uncomfortable with loud background noise. Either way, the challenge of reading visual cues arose. Camera angles that showed just above the shoulders hindered our ability to sense body language, which could be stressful and tiring for introverts, and boring for the extroverts in need of more stimulation. In addition, being on a call with dozens of people could be draining for those who naturally prefer smaller groups, like introverts.

Schools, either in person or online, have the ability to change for this sizable group to feel accepted. The kids who prefer to work alone shouldn’t be seen as outsiders nor told to participate more — this expectation demands us to rewire our brains. I have been told multiple times that if I were to “talk more,” I would “be happier.” Likewise, my participation grades have frequently been lowered because I have been vocally “dormant.” It can start to affect the self-esteem of many, including me, making us introverts feel our personality must be improved.

Allowing students both individual and in-group work time, as well as giving the option to students for either method, can accommodate both extroverts’ need for lots of stimulation and introverts’ need for less. Teachers can also change participation grades from solely speaking to including turning in assignments on time, coming to class punctually and being prepared and focused to include introverts more in this grading process.

Schools should nurture every students’ individual strengths, encouraging them to work hard in school and in later life. If the school-system focuses only on the strengths of a specific group, like extroverts, and tells all others to change so they fit that criteria, those who are different will feel unmotivated. Not only that, but the school’s goal of encouragement will be left unreached. With some simple adjustments to teaching styles, an awareness of students’ differences and a realization that introverts cannot be taught to be more extroverted, a balance can be found that welcomes the learning styles of all students — both introverts and extroverts.