The inoculation initiative: pushing to distribute the COVID-19 vaccine

February 12, 2021

A quick pinch. A couple of days of soreness. Wait a few weeks. Repeat.

After almost a year trekking through life amid a pandemic, vaccines have finally been authorized for

widespread distribution at sites nationwide. Here in Marin County, Marin Health and Human Services (HHS) has set up a point of dispensing (POD) at the Marin County Civic Center in San Rafael, where those meeting eligibility criteria can receive the vaccine after setting up an appointment with the clinic. The POD receives approximately 5,000 doses weekly and gives anywhere from 2,500 to 3,000 patients their first vaccination dose every week, according to the MarinHealth website.

Marin County Assistant Emergency Services Manager Woody Baker-Cohn has been involved in the establishment of the POD, working to fine-tune the process to maximize vaccine distribution rates for Marin residents.

“We learn a lot along the way, but I think we are really rocking it,” Baker-Cohn said. “A number of counties have come to us wanting to either visit the [Marin Center] POD or understand how we’re doing it because we’re so far ahead of most counties. It’s not like we’re geniuses. It’s sort of this virtuous feedback loop: we try something, it works or it doesn’t work, and we just keep adapting.”

Marin’s efforts mark the beginning of a push for large-scale immunization that county officials have spent months preparing for and anticipate taking months to finish. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has encouraged immunization of all Americans; vaccines deemed safe and effective by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which are currently restricted to those produced by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, have been evaluated using both data from their manufacturers as well as other clinical trials. Both vaccines prevent serious illness upon COVID-19 contraction and lessen the likelihood of contracting COVID-19 in the first place.

To maximize the rollout’s effectiveness, Marin has opted for a three-phased working model dictated by the state’s vaccination plan that outlines the vaccine’s release to various groups through the summer of 2021.

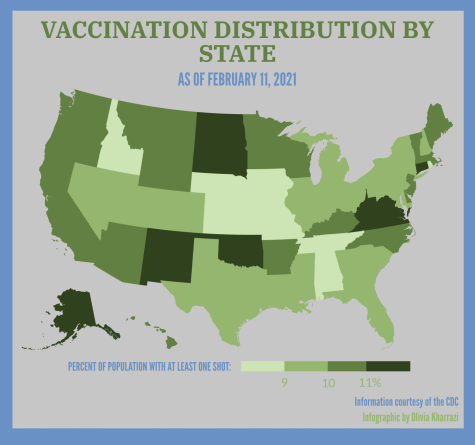

Across the nation, there has been a variety of different immunization methods, and these many modes of organization have often resulted in inconsistent success between states. Though initially expected to fall behind larger states, many predominantly rural states have been the most effective in their dissemination: Utah, North Dakota and New Mexico have currently distributed the highest percentage of their federally allocated doses at 103, 99 and 94 percent, respectively.

West Virginia is another rural state that has had success with its immunization efforts starting from early on in the vaccination process, having distributed 91 percent of their doses. According to the Brookings Institution research group, this is in part due to its reliance on independent pharmacies to distribute the vaccine; the state was the first to oppose engagement in the partnership the federal government formed with CVS and Walmart to inoculate long-term care facility residents. In South Dakota, where 83 percent of doses have been distributed, the three main health networks have divided the state into sections to distribute to, holding medical facilities responsible for administration, says CBS News.

Some of the most populous states are the ones that have fallen the furthest behind: Pennsylvania has distributed 63 percent of allocated vaccines, California has distributed 67 percent and Florida 69 percent. Early on, a potential common factor among less effective systems was more vigilant adherence to the CDC’s guidelines, which could be hindering more than helping, according to CBS News.

Many local officials look at the uneven dispersal successes as evidence for the nation’s faulty public health priorities; despite vaccine allocation being mandated at a federal level, states and counties have borne much of the burden of vaccine distribution planning. Dr. Gregg Tolliver, medical director of infection control at MarinHealth Medical Center, believes that vaccine distribution problems could have been partially prevented with adequate support and public health organization at a higher government level.

“Vaccine distribution is frustrating almost anywhere at any time. It’s never going to be perfect,” Tolliver

said. “In this situation, it’s certainly not perfect because you just don’t even know what’s coming down your supply chain, and the rules are changing all the time.”

Despite the Marin Center POD’s relative success so far in terms of vaccine distribution, frequent miscommunication –– or lack of communication altogether –– has complicated vaccine administration in Marin on the local level: not only are shipments often few and far between, but those received come with little or no prior notice.

“Right now, [the POD] knows usually less than a week in advance which vaccine we’re going to have, so

we’re trying to plan for staffing, space, suppliers and recruiting people to make appointments with less than a week’s notice,” Baker-Cohn said. “We’ve got a very flexible operation that’s doing amazing things, but that’s unsustainable. If we know what’s coming a few weeks out, that will make a huge difference and will ultimately lead to higher throughput and efficiency.”

For past emergencies, mutual aid from either other states or countries has been an integral part of remedying disasters. Unfortunately, the very nature of a pandemic makes this impossible, increasing the need for a dependable federal government. The Trump administration’s lack of guidance and fluctuating vaccine eligibility requirements consequently put pressure on local public health organizations to quickly adapt to these uncertain conditions. In less successful states, county oversight of immunization has resulted in overall disorganization.

According to CNN, the Biden administration found that there had been no vaccine distribution strategy in place whatsoever under Trump’s leadership, forcing the new administration to essentially create a completely new plan from scratch. Now, the change in leadership has roused optimism surrounding the future organization of the vaccine’s distribution for Baker-Cohn.

“With the new administration, it’s going to be a new world,” Baker-Cohn said. “We’ll have a better idea of what’s going on, and they’ll be focused on the right things.”

New priorities include hiring 100,000 health care workers to aid in the vaccination process and using federal disaster relief funds to compensate for the money states and local governments have had to use for immunization purposes. Biden has also requested $20 billion from Congress to broaden the scope of vaccination centers by including stadiums, pharmacies, doctors’ offices and mobile clinics. By enacting the Defense Production Act, he has worked to hasten the distribution process to further meet the need for vaccine supplies as well.

The new administration initially promised to inject 100 million vaccines in the president’s first 100 days in office, though Biden has since expanded his pledge to 150 million. Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna have committed to delivering 200 million doses by the end of March, and with the possibility of more contributions from other companies in the near future, the U.S. could have the resources for over two million vaccinations each day when the end of the month arrives.

Despite efforts to methodically organize immunization dispersal, the current muddled state of vaccine distribution systems has resulted in shortages of doses in some places and surpluses in others. The Marin Center POD, for example, has the facilities to work for seven days a week, but cut back to five because they were not receiving a sustainable amount of vaccines to stay open all seven days.

“I’m pretty confident that we can flex up to whatever comes our way,” Baker-Cohn said. “I think our challenge is going to be figuring out how to get [more vaccines] at the rate we can put [them] into arms or getting people to wait. Everybody wants it immediately, and very understandably.”

Conversely, at a clinic set up for COVID-19 vaccine distribution by the San Francisco Department of Public Health, there are frequently extra vaccine doses at the end of the day, whether they be due to no-shows or an uneven number of the doses in each vial, according to Redwood graduate Charlie Werner, an Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) for NORCAL Ambulance assisting with vaccine distribution at the San Francisco clinic.

“Every single time I’ve worked, we’ve had some extra [vaccines] at the end of the day,” Werner said. “[When we have extras,] the people working at the clinic who haven’t yet gotten it will be offered a chance to get the vaccine.”

Werner is one of the many EMTs authorized by the city of San Francisco to help with vaccination distribution. San Francisco and Marin have both now offered an expanded scope of practice for EMTs to allow them to partake in additional training to perform invasive procedures like vaccine injections, a step that has helped with staffing at vaccination clinics. The Marin Center POD has also partially remedied their own staffing struggles through help from volunteers from organizations such as the Marin County Medical Reserve Corps and the Marin County Search and Rescue team. Government workers have also been appointed to execute jobs that they would not do in their ordinary day-to-day work to help shoulder some of the vaccine distribution workload.

As the eligibility requirements broaden to include more populations, distributing the vaccine to all those eligible has often proven to be difficult. As California moves into Tier One of Phase 1B, those employed in education and childcare, emergency services and food and agriculture have become eligible for the vaccine, as well as individuals who are 65 years of age and older. As the scope expands, so do the difficulties in spreading information, especially when one of the primary ways clinics reach out to patients is online.

“The counties are struggling with how you get the word out to everybody, particularly the people that are most vulnerable,” Baker-Cohn said. “Many elderly people either don’t have email or don’t browse the web. They’re unlikely to get something electronically, so we’re trying to reach out through other networks.”

By working with organizations such as Vivalon and Meals on Wheels, the Marin Center POD has effectively reached out to the newly vaccine-eligible 75 years and older age group. The Marin Center POD is also planning to open smaller institutions for Marin residents who do not drive or for those located in West Marin, and have partnered with the Marin Community Clinic in the Canal District of San Rafael to open a POD there as well. Reaching Marin’s homeless population has also been a challenge, but help from the Marin HHS and various fire agencies county-wide have allowed the Marin Center POD to communicate and get vaccines to them.

Overall, the Marin Center POD has been, for the most part, successful with vaccine distribution given the current circumstances: 35, 214 people living in Marin have received at least one vaccine dose, or 13.5 percent of Marin’s total population, according to the California Immunization Registry.

Even while the vaccine roll-out begins to gain traction, it has been met by yet another obstacle: new COVID-19 variants. Though variants can always be expected of a virus, scientists have yet to determine their contagiousness and severity compared to COVID-19 as well as the effectiveness of the current vaccines against them. So far, the CDC has reported that the only known variant circulating the U.S. is B.1.1.7, a lineage that initially emerged in the United Kingdom and is associated with faster transmission and a possible increase in the risk of death, according to U.K. prime minister Boris Johnson. Whether this variant could increase illness or decrease the vaccine’s effectiveness is still being researched.

“Vaccines work best when there are low amounts of virus circulating,” Tolliver said. “Every time we put something into the environment, like a vaccine or a monoclonal antibody, we are asking for it to select variants that could potentially confer worse characteristics, like being easier to spread, and I think that’s already happened with some of these variants.”

As the variants arise, it becomes even more crucial for the continuation of the vaccines’ dissemination and the continued use of nonpharmaceutical interventions such as mask-wearing and social distancing to mitigate the risk of contraction. Especially with the impending imperfections of vaccine distribution, sole dependence on the vaccine against the virus remains unsafe.

“People need to continue to do pretty much all the stuff they’ve been doing,” Tolliver said. “The vaccination is kind of coming out to the population as the ticket, the exit strategy, but it’s not. It is only a part of the exit strategy. For a complex problem like the coronavirus pandemic, we need a multifaceted approach.”

Information last updated on 02/08/21.