Recovery starts with kicking the stigma of addiction

December 14, 2020

“Hunter got thrown out of the military … dishonorably discharged for cocaine use.”

I was sitting with my family watching the first presidential debate when Donald Trump made this remark about Joe Biden’s son, Hunter Biden, who struggled with drug addiction. And after the debate, when the country was in an uproar over Trump’s comments regarding the Proud Boys, or the candidates’ unpresidential behavior, I couldn’t help but think of my dad, who had celebrated 20 years of sobriety over quarantine. Once again, addiction had been sensationalized without addressing the root of the problem or those affected.

I grew up knowing my dad was a sober alcoholic; April 8 was always spent in a church or community center, my sister and I holding hands with him as he received his sobriety chip, our eyes blurred with prideful tears. As the years passed, we went from calling it “daddy’s allergy” to researching our family history of drinking and failed attempts at sobriety. From a long line of alcoholics who succumbed to their addiction, my dad got sober young, a feat I have trouble writing about without tearing up.

Regardless of political affiliation, drug and alcohol misuse is a medical issue, one that has only worsened during quarantine as binge drinking and drug use have replaced traditional social outlets. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, Bay Area residents drank 42 percent more alcohol during the shelter-in-place than they had prior, a trend supported by other news sources. In a country reeling from a racial reckoning, a worldwide pandemic, economic turmoil and a presidential election, condemning those who have chosen to self-medicate is cruel. Coming at it from a moral high ground, using someone’s addiction to sidetrack a political campaign, only adds insult to injury.

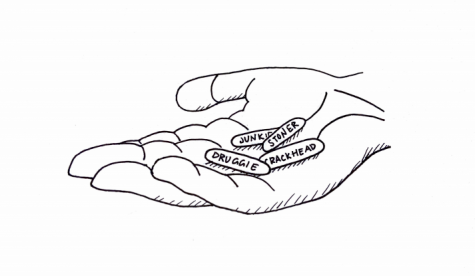

But this stigma is hardly new. In the 1980s, Nancy Reagan’s campaign, “Just Say No,” introduced the idea that those struggling from addiction were moral failures to kids at a young age. Even earlier, the Nixon administration synonymized addiction with their political enemies. As Nixon’s domestic-policy advisor said in a 2016 Harper’s Magazine article, “We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

The Nixon administration criminalized such drugs as an act of war on these communities, but they unintentionally caught over 31 million people and their families in the crossfire.

The effects of these attacks on addicts can still be seen today, most profoundly in society’s opinion of those who suffer from addiction. According to a Bloomberg School of Public Health article, the general public has more negative feelings towards addicts than towards those struggling with a mental illness. And when Donald Trump condemns addiction on a stage in front of 73.1 million people (according to CNN), this stigma only increases, which can deter addicts from receiving help.

If, conversely, the media showed the benefits of recovery and addiction success stories, this shame could drastically decrease. Regardless of my dad’s past, recovery turned him into a compassionate man, slow to anger and quick to forgiveness. I know these traits are partially attributed to his recovery and he and the other addicts I know actively spread this inner peace to others.

Unchecked, addiction has a ripple effect. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, there are more deaths from addiction than from any other avoidable affliction, with 750,000 deaths since 1990 from drug abuse alone, according to the CDC. While this number is high, it’s nothing compared to the mothers, fathers, siblings, friends and extended family impacted. Drug use is not a victimless crime; my dad’s family tree is pocked with alcohol-related tragedies: suicide, divorce, depression that caused estrangement with generational impacts.

But the same is true for recovery. My dad, his dad, his mom and his uncle are all sober, as are many of his high school friends. I know that, should I ever experience addiction, I will have the support I need to get sober, a sentiment I intend to pass on to my children. Just as my dad was born into a cycle of alcoholism, I was born into one of recovery.

As our country tries to gather its pieces, addicts are not often invited to the conversation. They are cast into the shadows and villainized in the media, with relapse used as a cheap plot point on TV shows. Instead, we need to bring them into the light, covering stories of redemption and recovery rather than those of overdose. My dad transformed from a depressed young man to a calm adult who meditates frequently and sponsors other recovering addicts in their sobriety. I cannot help but wonder if the same would go for more addicts if addiction was destigmatized in the media.