The academic pandemic

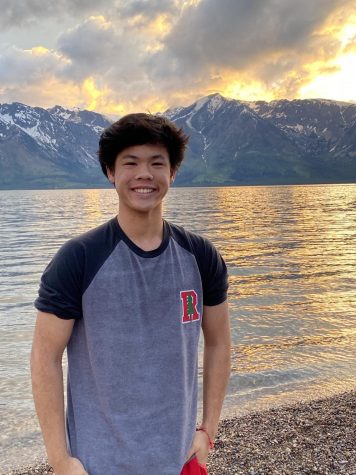

How staying remote has affected the emotional and academic well-being of students

December 14, 2020

For many students, each day on Zoom feels the same. The awkward silence is inevitable as the teacher asks the class a question and no one responds. Beds remain unmade throughout the school day as many merely sit up a little straighter in them in an effort to appear focused. Meanwhile, in a private school not far away, students pull up to another day of in person school, their lofty funding more than sufficient to pay for weekly testing and social distancing measures. And while these schools begin to heal themselves from six months of online learning, public schools only fall farther behind.

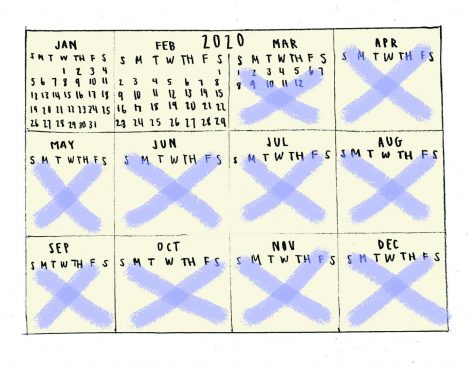

A two-week closure has turned into 10 months, and Redwood is still counting. On March 13, 2020, students’ lives changed and to this day continue to be impacted by the effects of a school closure with no definitive end in sight. As Pfizer and other pharmaceutical companies stir hope of an effective vaccine, students, parents, teachers and administrators alike wonder about the certainty of in-person school in the future.

California Governor Gavin Newsom’s children are currently learning from a classroom, as are many students attending private schools in the state. Marin has seen the re-openings of private high schools such as Marin Catholic and Branson as well as many public elementary and middle schools. However, for students in the Tamalpais Union High School District (TUHSD), re-opening is set but not guaranteed for January. Granted, smaller schools have an easier time maintaining social distancing than larger ones, but the inequity resulting from certain students remaining fully remote has severely widened the academic achievement gap between the haves and the have-nots.

Julie Norwood, a math teacher whose classes this year range from geometry A-B, the lowest level of geometry, to honors advanced algebra, Redwood’s highest level algebra class, has found that online learning negatively affects some students more than others.

“Every kid [in my honors advanced algebra class] does every assignment and comes to class every day; [distance learning] is really just not that big of an issue for them. Their grades are good. The attendance is good. We’re not covering as much content, but they’re learning what I’m teaching them,” Norwood said. “I’ve definitely felt the most struggle in geometry mostly because if you have internet issues, if you have a lot of things going on in your household, if you have a learning disability or if you’re an English language learner, all that stuff just gets magnified when you’re on distance learning.”

Norwood argues that students who already tend to struggle academically have taken the biggest hit from online learning, and she reports having more F’s in her geometry A-B class than ever before. Similar results have been seen across all Redwood classes, as the number of D, F or incomplete (DFI) marks has risen from 513 in the 2019-2020 school year to 974 in the 2020-2021 R1 grading period, with 1987 students currently enrolled, according to the Education Services Board Report.

“Kids are having trouble focusing, and then they’re behind. When they get behind there’s a tendency to just kind of give up a little bit,” Norwood said. “It is absolutely widening the [academic achievement] gap.”

Online learning has also caused a tremendous amount of racial inequity in the TUHSD. The Education Services Board Report recorded that 40.8 percent of Black and Hispanic students received a DFI compared to 23.8 percent of all students receiving a DFI in the R1 grading period. In response to the report, Dr. Kimberlee Armstrong, TUHSD’s assistant superintendent of educational services, spoke with the Marin IJ.

“While this report is concerning, it’s done what it’s supposed to do, which is to fire off alarms and get the traffic cam blinking. It’s led to more conversations and accommodations for students,” Armstrong said.

Despite these new accommodations that include new learning hubs across the district, many students, parents and teachers remain wary of distance learning’s long term impacts, including Redwood mother and middle school teacher Mary Bender.

“The worst thing you can do to someone is isolate them. That fact of humanity is being ignored,” Bender said. “Most kids do not like high school. They want to get away with as little as they can to get what they want, and distance learning enables them to do that even more now that they’re not being supervised.”

Conversely, Kathryn Ghiraldini, an academic workshop and English teacher whose classes rely heavily on discussion and interaction, is fearful that the beneficial pieces of online learning may not be available once Redwood goes back to in-person learning.

“Feeling the heartbeat and the energy of the room is a valuable component of debate and discussion,” Ghiraldini said. “On the flip side of that, there’s something wonderful about being online because students who would otherwise not speak are participating in alternate ways, like the chat [on Zoom]. I have these students who I’m wondering how to keep engaged when we go back because there are students who I haven’t heard their voice once, but they are very valuable contributors to my classes.”

Despite Ghiraldini’s noted benefits of online school, the deprivation of daily social interactions and the hours spent hunched over staring at a screen has undoubtedly taken a toll on teens’ physical and psychological well being. Emily Tejani, MD, a UCSF psychiatrist with a private practice specializing in children and adolescents in Marin, emphasizes the impact of the pandemic on young people in particular.

“We are now seeing higher rates of psychological distress amongst all age groups and particularly adolescents and young adults,” Tejani said. “We have seen a huge surge in anxiety, depression and substance use in teens and college students. Recently, they seem to be the most impacted from a mental health standpoint due to the pandemic at large, but there’s even a little data to suggest that the school closures specifically are contributing to worsening mental health states and outcomes.”

Bay Area students are not exempt from the distance learning struggles, according to UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital in Oakland. Mental health screenings in September 2020 revealed a 10 percent rise in suicidal thoughts in children ages 10 to 18 across Bay Area counties since March 2020. The stakes are high, and experts are calling for school policymakers to acknowledge the pressure of getting students back in schools.

“I think it’s highly likely that we will be seeing effects of this pandemic for years to come, if not generations to come, especially for people who are young right now,” Tejani said. “There’s a misconception and misinformation about how adversity and stress affect people, especially young people. A lot of people who aren’t in the mental health or medical field believe that stress and adversity make a person stronger, but actually, the opposite is true.”

Along these lines, in an interview with the Harvard Gazette, Joseph Allen, associate professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, also emphasized the need to consider the risks of ongoing distance learning.

“Right now, occasionally we’ll see a case of COVID-19 in a school that will make headlines. But you can predict the headlines we’re going to see in the coming months and years about kids who disappeared from the system, the virtual dropouts, the loss of learning [and] the loss of income, which we know happens when kids are left behind with schooling,” Allen said. “This is a national emergency. That’s not overstating it.”

Many Redwood students and parents share Allen’s view. A survey given by TUHSD in early November showed that approximately 90 percent of students wish to return to in-person learning. The rate of return, however, is causing 120 sections at Redwood to be over the 15 student classroom capacity. The combination of exceeded classroom capacities and limited outside space for lunch has forced the administration to create three cohorts upon the return to in-person learning as opposed to two.

Because three cohorts will only allow students to be on campus about once a week on average, Norwood believes returning to campus may be ineffective.

“I wish that there was a way for us to not break up into three groups. Three groups almost makes it not worth it. I’m going to expose myself to thousands of kids every day who might have COVID-19 possibly just to see a kid once every two weeks.” Norwood said. “If we could see them four times a week or even twice a week, the benefits would be a lot higher.”

While going back in-person is an option for students, according to superintendent of TUHSD Tara Taupier, non-high-risk teachers do not have a choice with the hybrid model.

“If [teachers] don’t have a medical reason to stay remote, then they would have to take an unpaid leave if they don’t want to work [in-person],” Taupier said.

As plans continue to advance, Ghiraldini has seen the negative effect the process has had on her coworkers.

“It’s a really divisive thing that’s happening because health and politics are so entwined here. It’s a really interesting landscape and current event to be a part of and to be witnessing as a teacher,” Ghiraldini said. “I think that there is some damage that’s going to be done to morale if teachers don’t feel that their voices are of value in the decisions that are being made.”

Despite the concerns regarding in-person school come January, Dr. Lisa Santora, Marin’s deputy public health officer, believes that opening schools will not reap health hazards across the county.

“It’s important to note that most counties across the state that did not reopen schools are seeing even faster rises in cases in people of all ages,” Santora said in a mid-November Marin Health & Human Services report. “We’ve done a lot of work together to make sure that schools can reopen safely, and it’s paying off.”

However, Principal David Sondheim fears that, unless cases stay low, a return to a hybrid model is not guaranteed.

“It is critical that students, parents, administrators and teachers follow guidelines. I know it is a challenge but I’m deeply concerned about a rise in cases affecting school openings in January,” Sondheim said.

At the end of the day, positive COVID-19 cases are the greatest determinant in whether or not Redwood sees a reopening in January. Marin was in the red tier as of Dec. 8, but if cases rise and it moves into the purple tier, then school will not open until it returns to the red tier. The TUHSD’s reopening is reliant on students, parents, teachers, administrators and other community members following county guidelines. Without the support and trust of one another, students will remain at home and progress will be forgone.